A Geometry of Desire

René Girard's Mimetic Theory, Part 1

Over the past few years, there’s been a growth in interest in the French literary theorist René Girard and his notion of “mimetic desire.” A lot of this interest is generated because of his association with Peter Thiel, who studied with Girard at Stanford, became something of his protégé, and who claims to draw on Girard’s ideas for business and politics. What are those ideas? It’s actually one idea, an idea that can appear so straightforward that it suggests profound simplicity and axiomatic elegance or such a superficial and obvious truism that makes one suspect the legerdemain of a charlatan: imitation of others’ desires holds the key to the human condition. As Girard wrote, “Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires.” But these imitations of desire do not just create a world of bland consumerism and conformity. For Girard, who has been called “the prophet of envy,” mimetic desire is the source of jealousy, rivalries, bitter conflicts that can lead to apocalyptic paroxysms of violence

In a fitting fate perhaps for a philosopher of imitation, Thiel’s fixation has bred many copycats who try to make knock off Girardism as “one weird trick” for success in business and life. As Sam Kriss wrote recently for Harper’s, interest in Girard also runs through the intellectual right, from its extremes to whatever remains of its center. Recently, Catholic University of America put on its first Novitate conference, celebrating the centennial of Girard’s birth and featuring a keynote address by Thiel himself. The conference also featured a number of intellectual luminaries of the right and center-right. Thiel was not the only representative of the business world; one panel was titled “Architects of Desire: Building, Teams, and Culture,” and featured the head of Christian Dior North America, a Miami real estate developer and the assistant G.M. of the Suns. In fact, the entire conference was hosted by one Luke Burgis, someone whose title is “Entrepreneur-in-Residence at the Ciocca Center for Principled Entrepreneurship at Catholic University of America” and its “goal is to bring together three metaphorical cities: Athens (reason), Jerusalem (faith Traditions), and Silicon Valley (innovators in business and beyond).” (God, please help us.)

Considering the broad acceptability of and interest in Girard to many different segments of this fragmented coalition, it makes sense to try to bring together a conservative gathering under the aegis of his thought. From a sociological perspective, this conference can be read as an attempt a forge a new fusionism that could unite the secular and religious right and a reconstitution of the old conservative movement as an alliance of ideologists and business interests.

I believe what Girard’s phenomenology of desire, envy, jealousy, and rivalry can provide conservatives is a partial critique of the commodity form and the market society, without thereby having to jettison private property or social order. He appears to provide an answer to the problem of what Marx once called “fratricidal competition” and thought was an inescapable cycle of the capitalist system. Girard allows Thiel to imagine he can retain the order and value-producing side of capitalism, but jettison the abstract, alienating, and crisis-ridden side.

In the eyes of Thiel, Girard’s strictures against invidious competition, makes him a perfect theorist of monopoly capitalism, which, in Thiel’s mind, can miraculously defeat the logic of the market and commoditization and can focus instead solely on “innovation,” that is to say, the pure creation of use-value, rather than having to bother about the exchange-value of products. Here is how Thiel describes his commercial philosophy in Zero to One, his Girard-inspired business book: “Americans mythologize competition and credit it with saving us from socialist bread lines. Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away. The lesson for entrepreneurs is clear: if you want to create and capture lasting value, don’t build an undifferentiated commodity business.”

By eliminating competition, which Thiel seems to think is merely a “mindset” rather than a social fact occasioned by our mode of production, even the problem of money can be solved: “In business, money is either an important thing or it is everything. Monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money; non-monopolists can’t. In perfect competition, a business is so focused on today’s margins that it can’t possibly plan for a long-term future. Only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits.” Of course, monopolies have long suggested to socialists the implicit outline of a future coordinated economy, but Thiel thinks he can solve the problems of capitalism not by a leap forward to socialist planning, but like so many reactionaries before him, by stabilizing the world through a fantastical return to the Middle Ages and the reimposition of feudal social relations—a make-believe world of ”serfs and lords, vassals and suzerains, laymen and clerics.”

Girard’s followers sometimes vaingloriously label him the “The Einstein of the Human Sciences”or “Darwin of the Human Sciences.” But, even more than Hegel perhaps, he’s kind of the Napoleon of the Human Sciences. (Not for nothing perhaps is the central novelist of his system Stendhal, who was a bureaucrat under Napoleon’s regime.) What Girard provides to modern right-wingers is a Bonapartism of the spirit: He shares with Napoleon a megalomanic ambition to conquer the entire world—albeit only in the realm of theory. And like the Emperor, he can appear, in one light, sublime and inspiring, in another, ridiculous and petty. He can be all things to all people: he is half-feudal and monarchical, half-Enlightened and liberal. He allows for a concordat with the Church, without necessitating a belief in God. He supports the big bourgeoisie. He understands the need for fancy costumes. Most importantly, he allows for the creation of new titles nobility. Hs theory is sometimes appears nearly identical to Napoleon’s famous piece of cynicism: “A soldier will fight long and hard for a colored piece of ribbon.” He teaches, as Napoleon said, “that imagination rules the world;” that our desires come from images in culture and our fantasies about each other. (Napoleon was actually quoting Pascal there and so in many ways is Girard.) For the billionaire, he offers an illusion of domination and control of the entire world; he provides spurred-boots and a bridle to these would-be lords and ladies: desires for honor and riches can here be prodded, there reigned in—for the sake of social peace.

To be fair to Girard, there is more to his theory than this wish. And he would probably object that such fantasies of domination and control are the very opposite of what he intended to foster. But, as with Napoleon, it must be admitted that there is something a little cult-like about the Girard phenomenon. A lot of the secondary literature about Girard, comes off at times as apologetic, defensive, or overly-laudatory. It tends to focus to an unseemly degree on the personal virtues and charisma of Girard and wants to convince that this individual is not just an intellectual of high standing, but also an adorable man and great sage. Critiques are often not dealt with systematically or according to their arguments, but just waved aside as fundamental misunderstandings. And even though he is a thinker who is focused on the centrality of imitation, his disciples are also at pains to insist his insights are totally original and earth-shattering, although they were originally presented as the discovery of abiding themes in literature.

Whenever a kind of cult of personality grows up around a figure, it’s worth putting them into context. And the most important context for René Girard is France, the country of his birth. In fact, there is something almost generically French about his theoretical output: I texted a passage of Girard to a friend and she immediately responded “Barthes?” One is also tempted to joke here that only a Frenchman could find ontological significance in the love triangle and attempt to found first philosophy in a meditation on the manipulative techniques of the coquette. Girard would be the first to admit this thoroughgoing Gallicism; he was brought up with faith both in the Church and the Revolution: “I was raised in the double religion of Dreyfusism and Catholicism (on my mother’s side)…” This figure of “double religion,” of, on the one hand, intense Catholic piety, and, on the other, the rationalistic universalism of the Revolution, provides one key to Girard’s thought: he straddles an Enlightenment tradition that is critical and even satirical, concerned with an egalitarian deflation of titles and pretensions, but also Counter-Enlightenment, apologetic one, which, as in the works of Bonald or Maistre, finds the sin of envy behind revolutionary egalitarianism, defends the social role of religion, and the wisdom of traditional hierarchy. Again, this half-Enlightened quality allows for the employment of Girard’s thought as a piece of cynical reason invaluable the right: All putatively egalitarian values can be dismissed as merely the product of resentment, all declarations of political principles as so much mindless mimicry.

This “double religion” also maps onto a central divide in French thought that recapitulates itself in Girard: on the one hand, there is Descartes, the tradition of the clear mind, analysis, rationalism, deduction, geometry, and, on the other, the tradition of Pascal, of the heart, faith, feeling, judgment, and intuition. This divide corresponds to Pascal’s own differentiation of an “esprit de geométrié” and an “esprit de finesse.” It’s tempting to apply the metaphors of light and darkness to this opposition, but these are both traditions of intellectual clarity: Descartes represents the clarity of method, carefully and correctly followed, while Pascal represents the clarity of grace and conversion, the sudden lightning-bolt, the life-altering revelation of the truth. But Pascal’s clarity is, to borrow from his contemporary Milton, a “darkness visible”: it illuminates a world of sin, folly, and vanity. Of course, underneath their apparent differences is also a profound similarity: Pascal was a mathematician and Descartes goal was to prove the existence of God. Descartes thought the mind of man could systematically discover rational proof of the existence of God; for Pascal, the meagerness and perversity of man necessitated faith in God: at times, Girard seems to believe he can systematically prove the existence of God through man’s perversity.

In 1961, when René Girard published his first book Mensonge romantique et Vérité romanesque — which translates literally to “Romantic lies and novelistic truths,” but was translated into English as Deceit Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure—France’s intellectual life had just undergone a shift: the Phenomenology and existentialism of Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and de Beauvoir had given way to the structuralism of Levi-Strauss, Althusser, and Lacan. Both these tendencies have their Cartesian and Pascalian sides. Phenomenology, was, on the one hand, like Descartes’s method, a process of radical introspection that attempted to ground rationality in the intentional structure of consciousness, but it also took seriously Pascal’s “reasons of the heart” and provided tools to investigate the emotional, embodied, and affective—and with it the tragic, morbid, and pathological—aspect of experience. Structuralism was an almost literal application of the spirit of geometry: by using a formal method, the abstract shapes underlying language, culture, and thought itself could be discovered, but it also involved a total deflation of the pretensions of subjectivity. Man is trapped in a “Prison-House of language,” to borrow Fredric Jameson’s memorable phrase, or, really, he was just an effect of the system, a kind of illusion or epiphenomenon. Pascal wrote that “the self is hateful.” The structuralists took it even one step further: "The self is not only hateful," Claude Levi-Struss wrote in Tristes Tropiques, "there is no place for it between us and nothing."

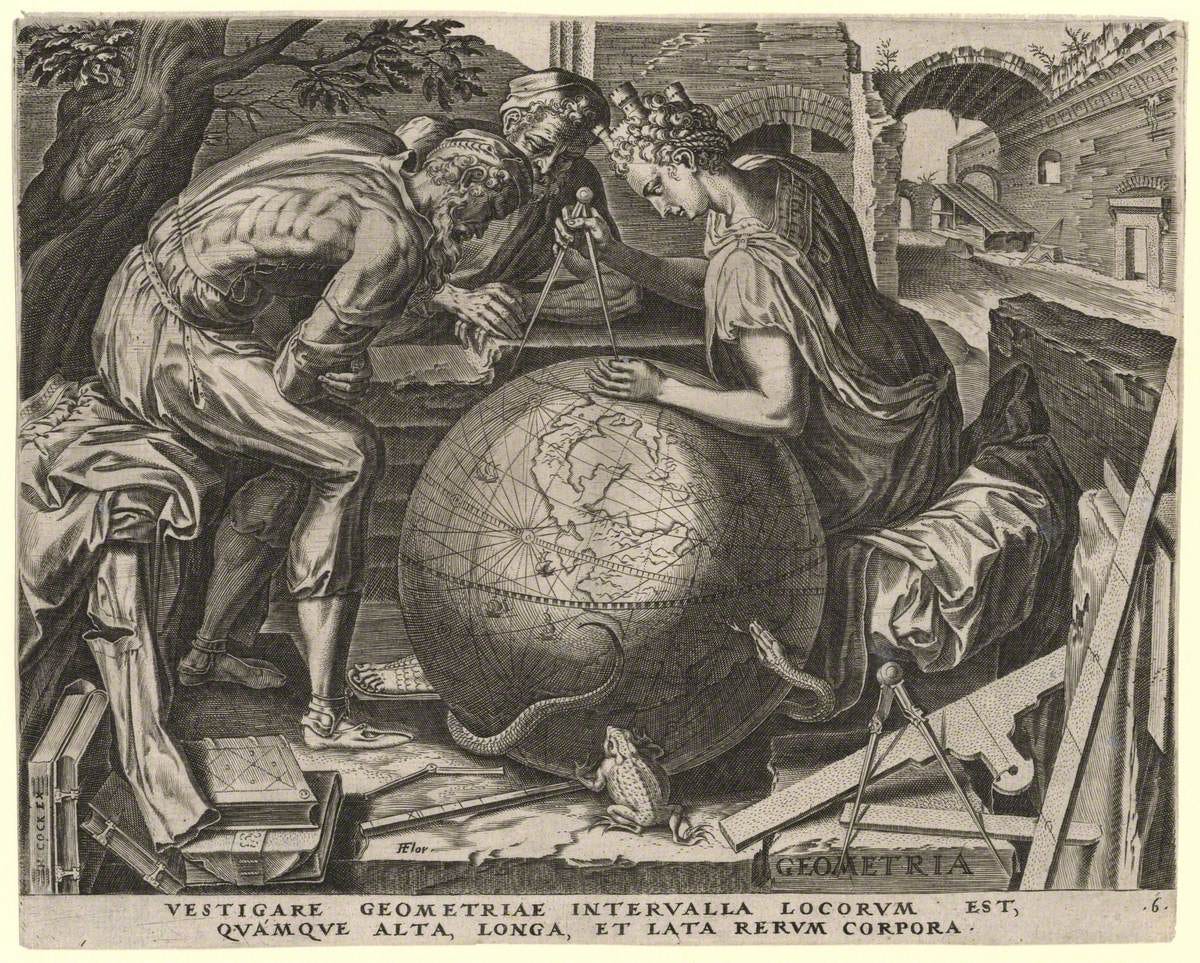

Mensonge romantique, a work from this transition period in French thought and from the time in Girard’s own life when he converted to Catholicism, borrows from and attempts to fuse both traditions. It is in part a Sartrean phenomenology of the fundamental lack at the center of the human self and a structuralist reduction of the status of the transcendental subject. For Girard, romanticism gives us a false picture of an autonomous subject whose desires are their own, most special thing, while the novel—or at least, the truest novels—reveals that the self is never autonomous and its desires are not “the emanation of a serene subjectivity, the creation ex nihilo of the divine ego.” Great novels give us the plans, if not always the keys, to the prison-house of desire: “A basic contention of this essay is that the great writers comprehend intuitively and concretely, if not formally, the system in which they were first imprisoned together with their contemporaries.” At the heart of human relations, Girard believed he had found one simple, recurring, constant figure: the triangle. Armed with his compass, he thought he could provide proofs for what Pascal once deemed impossible: a geometry of the soul.

But this is getting rather long, so I will leave it there until next time!

Really fascinating glance at a thinker I knew nothing about, thanks John.

There's a parallel I think between monopolistic capitalism in the economic sphere and a disdain for constitutionalism and republicanism in the political one. There's a kind of folk wisdom in the sense of "really we just need to overcome all of this petty competitive squabbling and have some kind of monopolistic power so we can focus on actually getting things done."

That reasonably holds up to scrutiny as long as we begin with the premise that your desires are base, self-destructive and ill-informed, while mine are rational, forward looking and designed to create a better tomorrow.

Really interesting! Not sure this is particularly germane, but it seems that the advocacy of monopoly capitalism reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the economic theory. First, the theory of perfect competition states that in equilibrium "economic profits" are driven to zero - which is confusing since it does not mean that the return on capital is zero - capital earns the minimum necessary return to justify its use in a given activity. Economic profits are called "rents" to distinguish them from "normal" profit. Second, under almost any economic theory monopoly diminishes welfare - to sidestep this is just willful distortion. Third, these advocates ignore or reject the logic and consequences of market failure, even though it is embedded in the theory of perfect competition itself. I've always found it bizarre that so many on the right claim to take their cues from economic theory, while wilfully ignoring its logical consequences.