Anti-Democratic Vistas, Part I

The Right Goes To Hungary

Back in 2012, I visited Budapest. This was during Orbán’s second premiership and after the parliamentary elections of 2010, when Fidesz’s alliance won a big enough majority to make constitutional changes. It was already clear where things were heading: by this time they had gerrymandered parliamentary districts, the civil service was being purged and filled with Fidesz loyalists, and the media was coming increasingly under state and party control. Jobbik, at that time a far-right, barely-crypto-fascist party, had entered the parliament for the first time with a significant number of seats. Both Jobbik and Fidesz candidates used antisemitic and anti-Roma rhetoric in their campaigns and in office. One Fidesz MP said in an interview, “I love my homeland, love the Hungarians and give primacy to Hungarian interests over those of global capital – Jewish capital, if you like – which wants to devour the entire world, especially Hungary.” In 2012, a Jobbik MP called for a “list” of Jews living in Hungary.

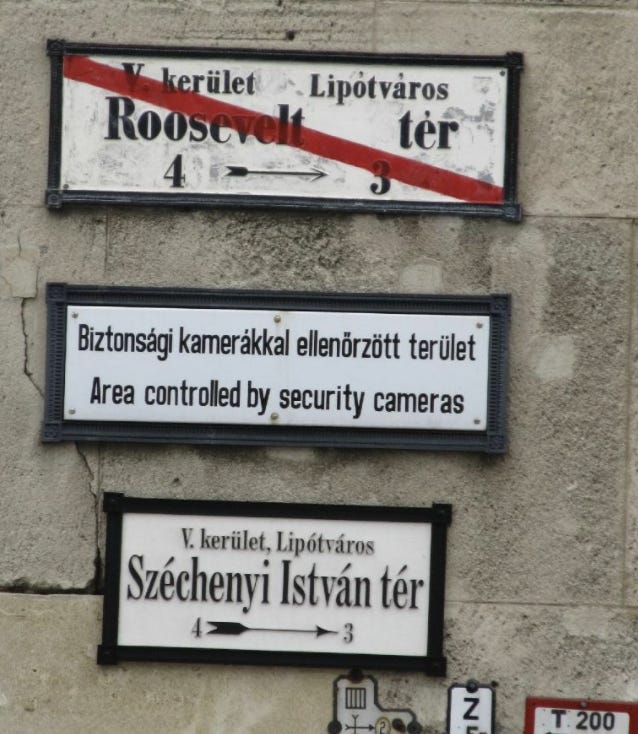

I noticed mostly symbolic changes: the square on the Pest side of the famous Chain Bridge was formerly named “Roosevelt tér;” it had been renamed Széchenyi István tér, after the 19th-century moderate nationalist statesman, who had feared the possible fusion between radical nationalism and the reactionary feudal nobility. They did not simply replace the sign, but had to leave an ex-ed out version of the old sign. It’s their country; I am not so much an imperialist to decree they have to name their streets after our presidents, but I have to say seeing F.D.R’s name pointedly crossed out disturbed me and even made me a little angry.

One other episode really gave me the creeps. There were a lot of shops selling t-shirts depicting Árpád and other Magyar tribesmen on horseback with old Magyar runes. I knew they were nationalist propaganda, but I liked them in a of kitschy way, so my then-girlfriend and I went into a little shop that had them displayed outside. My girlfriend, who is half Hungarian-Jewish, started chatting in Hungarian with the owner of the store, a middle-aged woman, while I checked out the wares. I didn’t recognize many of the books but I noticed one title and author I knew: The Labyrinth, the memoirs of SS-Brigadeführer and Sicherheitsdienst chief Walter Schellenberg, better known to popular history as one of Coco Chanel’s boyfriends. It dawned on me that most of the other books were fascist or extreme nationalist, as well. I said to my girlfriend, “We have to leave right now.” In the street, she told me that the owner was pressing her about where we were from and what language we had been speaking when we walked in. That experience sort of sums it all up: harmless-seeming nationalist kitsch on the outside, the real Nazi stuff on the inside.

Budapest is a beautiful city and its not hard to see how it can inspire romantic sentiments in American right-wingers. It’s almost a cartoon version of a Central European capital, a vision out of a Tintin comic. It’s also not very cosmopolitan: almost everything is Hungarian, besides some traces of Ottoman rule and the somewhat artificially preserved remnants of Jewish life. This wasn’t always the case. The population of Hungary and its capital was once made up by a mix of other nationalities. Slovaks, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, Germans, and Jews taken together outnumbered Magyars.

The crossing out of the “Roosevelt ter” is part of the ongoing process of “Magyarization,” the assimilation of the population to Hungarian language and culture that started in the 19th century. The pre-requisite renewal of Hungarian language was the project of the radical intelligentsia: Ferenc Kazincky had been imprisoned by the Austrians for participation in a Jacobin conspiracy. Before it had any political expression, nationalism was primarily a literary movement, confined to the romantic imagination. Lajos Kossuth, the journalist and radical democratic opponent of Istvan Széchenyi, was a strong proponent of rapid Magyarization. It’s not too much of a simplification to say that Magyar nationalism was a “left-wing” or at least liberal position during much of the 19th century, with its proponents envisioning national unity based on civic equality on the model of the French revolution.

Idealism notwithstanding, this did not always go down well with the other nationalities. The explosive revolutionary period of 1848 did not see the other nations embracing their designated role as legally protected “minorities” in a united Hungary. They had their own national aspirations, which were not compatible with all-embracing Magyar nationalism, a division that was used to great effect by the Austrian overlords of Hungary. One exception to this trend were the Jews, who were emancipated by the liberal reformers, adapted to Magyar language and culture, and even became fervent patriots. Their enthusiasm for the national project was to be repaid with hatred and resentment in the next century. (Hungary, and particularly Budapest, was a relatively tolerant bastion and did not have the same explosion of antisemitism as the rest of late 19th century Europe, although it had its own “Dreyfus Affair,” a blood libel case in the 1880s. Always a little behind developments in the rest of Europe, Hungary would only develop a full-fledged antisemitic politics after World War I.)

Hungary was the product of the 19th century; it’s not too much of a stretch to say it was created by intellectuals, mostly drawn from the liberal minor nobility. Budapest was the late 19th century amalgamation of three separate towns and its architecture, especially on the Pest side, is largely neo—: neo-Gothic, neo-Baroque, or neo-Renaissance, sometimes with pastiches of several styles. This contributes to its Tintin or even “Epcot” feeling: that of being ensconced within a self-contained national totality, a feeling also encouraged by the island-nature of Hungary’s peculiar language, a Uralic tongue with no close relatives nearby.

Given the enormous effort in the preceding century to create a rounded, organic national and cultural whole in Hungary, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Hungarian philosopher Georg Lukacs focused so obsessively on the concept of totality, which he took from Hegel and the German Idealists. Lukacs’s pre-Marxist The Theory of the Novel presents the re-creation of totality to be the main artistic task in modernity. While epics reflected the underlying unity of a traditional and ‘integrated’ culture, disenchanted modern life denies us this sense of totality, leaving the subject in a state of “transcendental homelessness,” longing nostalgically for its place in the world. “Once this unity disintegrated, there could be no more spontaneous totality of being. The source whose flood-waters had swept away the old unity was certainly exhausted; but the river beds, now dry beyond all hope, have marked forever the face of the earth.” New artistic forms arise to meet the challenge of this situation: “The novel is the epic of an age in which the extensive totality of life is no longer directly given, in which the immanence of meaning in life has become a problem, yet which still thinks in terms of totality.”

For Lukacs, the novel is the art-form of “virile maturity” as opposed to the “childlike epic; it does not just try to replicate the old organic unities, but, with the use of irony, still takes into account the contingency, fragility and possible meaningless of the modern world. But, to the superficial gaze of the political tourist, Orbán’s Hungary, ultimately the product of the 19th century romantic imagination, seem to have recaptured the homogenous totality of the pre-modern world. In art criticism, the name for this move is “kitsch.” In political theory, this fantasy is one of the constituent elements of fascism. Such a fantasy is more difficult, maybe even impossible, to sustain in the United States, with its inescapable plurality and dissonance at every turn, lacks what Lukacs called the “completely rounded architecture of the system.”

It’s interesting to note that the Orbán regime restricted access to the Lukacs archive in Budapest, leading to fears that they would actually destroy the contents. This is superficially because of Lukacs’s association with the Communist Party and his admittedly shameful political moves during that era. But it’s almost funny that they viewed these dusty Marxist papers as so threatening that they had to prevent people from getting at it. Around the same time, the regime removed the monument to Imre Nagy, the dissident Communist hero of the 1956 Revolution, which will be the subject of the next post.

John, the hyperlink at "a Jobbik MP called for a “list” of Jews living in Hungary." seems to be broken -- it redirects to a private substack page. Do you mind re-linking to the article?

Absolutely love this series and look forward to the next installment! It's a perfect counterpoint to the right's ahistorical, decontextualized embrace of Orbanism. I do wonder if Carlson, et. al are just trolling everyone with the trip to Hungary, though there's actually no practical difference between trolling and taking an idea seriously on the American right anymore.