Céline in Context

The Career of a Nihilist

This post, dealing with the writing of the French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline, contains violently obscene and racist language.

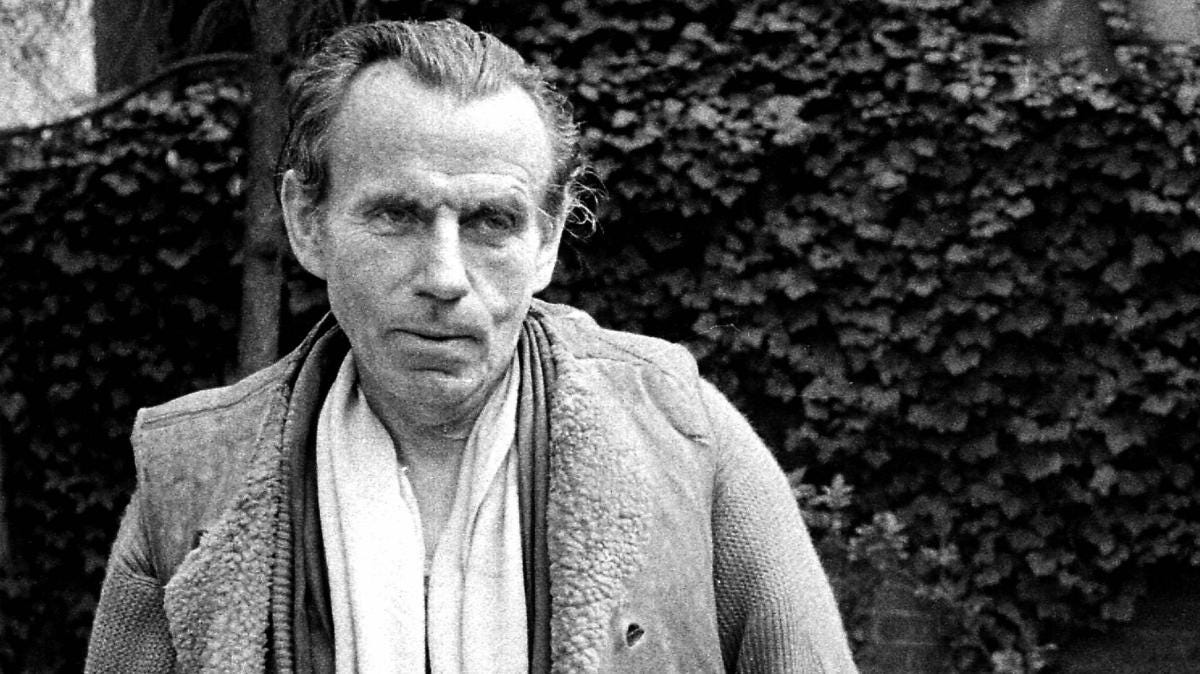

On The New Republic website, there’s a review of a new book by Damian Catani on the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline. The review duly notes the ongoing controversy over whether to celebrate or even read an author who was a notorious antisemite and Nazi sympathizer, but it does not really address any details of what Céline wrote on the Jews or how his writing fit into the political and social context of the Popular Front years and occupation. Whatever literary merits or moral demerits he deserves as an author, Céline’s career is important cultural history: he represents one the most extreme and perverse expressions of antisemitism, coming not from the traditional far right but from the artistic avant-garde. His antisemitic writing was met not with disgust and dismissal, but was received by a curious, titillated, and even sympathetic public. As such, his work provides valuable evidence of the spiritual and intellectual condition of Europe before the war and the complicated and contradictory milieux of fascist sympathizers, particularly in the cultural elite. I’m going to briefly take a look at Céline through the eyes of historians rather than literary critics.

With the publication of his Journey to the End of Night in 1932, Céline became a major writer. Based on his experiences in the First World War and his post-war travels as a physician, the novel is hallucinatory, apocalyptic, and bleak. It denounced bourgeois hypocrisy, nationalism, militarism—all the pillars of respectable society. It had the power to “appall” and “astonish.” French critics loved it. Sections of both the French Left and Right tried to claim Céline as their own, but he stood aloof and disdainful of all. The historian Michel Winock records:

In 1937, during the height of the Popular Front, Céline chose his side with the publication of the pamphlet Bagatelles pour un massacre. The pacifist, anti-militarist Céline wrote: “I say it straight as I believe it to be, that I would prefer twelve Hitlers to one omnipotent Blum. Hitler I could even understand, whereas Blum is useless, will always be the worst enemy, absolute hatred to my last breath.”

For Céline, Jews like Blum were responsible the decadence and decline of France. Robert Soucy writes:

If, for Celine, Marxists and liberals were major villains, behind them, orchestrating their activities, were always the Jews. The Freemasons were "willing Jewish work dogs, rooting about in all the trash barrels, in all the Jewish garbage"; "The Jews are our masters— here, yonder in Russia, in England, in America, everywhere!” The Jews infiltrated revolutionary movements, granted the vote to the ignorant, poisoned relations between labor and management, forced the wealthy into debt, multiplied economic crises, enslaved nations, and caused hunger and privation. Jews controlled the major levers of power. All French trusts, all French newspapers, and all French banks were Jewish. Work alone was Aryan. Three-quarters of the national wealth of France belonged to the Jews. The Sorbonne had become a ghetto and a "high pressure synagogue," while art, which should be "nothing but Race and Fatherland," was also controlled by the Jews.

This paranoia labeled non-Jews Jews on some spiritual level: “Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt (Rosenfeld), Neville Chamberlain, and even the pope (whose real name was Isaac Ratisch) were Jews.” Perhaps not surprisingly, there was a psychosexual current as well:

Céline's tirades against the Jews expressed both sexual fear and sexual jealousy. According to Celine, Aryan men were often raped by domineering Jews, while Aryan women found Jewish men especially attractive. Jews were like blacks in the sexual appeal they held for women: "A woman is by birth a treacherous bitch. . . . Womankind, especially the French woman, is ecstatic about kinky hair, about Ethiopians, they've got awesome pricks I'll have you know.” Thus in Céline's mental universe, misogyny and racism reinforced one another. [Soucy]

The brutal nihilism Céline brought to bear on the bourgeoisie now found an obsessive focus in the Jews:

One of the hallmarks of Céline's thought was the pride he took in being a tough-minded realist, in being contemptuous of anything that smacked of Victo rian hypocrisy, humanitarian sentimentality, or liberal tenderness. This was reflected in the style as well as the content of his writings. He preferred crude profanities to genteel euphemisms, his anti-Semitic pamphlets being peppered with such words as ass, cock, shit, buggered, and so on. In Céline's case, how ever, there was more to his profanity than simple intellectual honesty or linguistic frankness. His profanity sought to hurt, damage, and destroy, to express the most violent impulses in the most scurrilous language, to foment hatred for Jews, blacks, liberals, democrats, women, and a host of other scapegoats.[Soucy]

In the ostensibly pro-worker policies of the Popular Front were just hidden methods to corrupt the French race:

How did the French public respond to this outburst of obscenity? Relatively mildly. "In the France of the 1930s, antisemitism enjoyed real respectability,” Michel Winock writes. “It belonged to a cultural and political tradition that was dictatorial; it was a commonplace passion. In his unbridled book, Céline was original in only one respect: he was a writer who had perfectly mastered his art, the art of rhythmic vociferation, of an unleashed imagination, the art of delirium.”

Céline drew on—plagiarized really—the entire literary corpus of French antisemitism going back to Edouard Drumont and the newer brochures from Nazi Germany. Critics interpreted it as ironic, a kind of joke, satire in the vein of Swift’s “Modest Proposal” travestying the antisemitic views of his petit bourgeois origins. André Gide thought if it was not some sort of game, Céline had gone “completely nuts.” Céline’s quickly proved his sincerity through his open celebration of the defeat and his enthusiastic collaboration with the Nazi occupiers.

What turned Céline, who had friendly personal relationships with Jews, into a violent antisemite? There are a number of different psychological interpretations, which I won’t go into here. Sartre believed he did it for money. Motivations aside, Winock reminds us, “What is certain is that Céline wrote a malicious book at a time when France was experiencing an anti-Jewish outbreak: this time, far from going against the current, he was on the side of those who were setting the tone.” Money may not have been the primary motivation, but a careerism of another kind, one present even among writers who foreswear material gains: His passionate expression of hatred can be read as the consequence of matching his aesthetic commitments to brutality and disgust with a powerful current of public sentiment.

This post prompted me to re-read Orwell’s wonderful 1940 essay, “Inside the Whale”, ostensibly a review of “Tropic of Cancer” but mostly a reflection on the political culture of inter-war literary intellectuals (mainly English, but the pre-fascist Celine of “Journey to the End of the Night” is mentioned). With typos, here’s the essay, if anybody’s interested in this kind of contextualization of John’s piece: https://orwell.ru/library/essays/whale/english/e_itw

Just read Celine's late career trilogy (North, Castle to Castle, Rigadoon) and he comes off as less a diehard true believer than a sniveling lackey, a groupie type who'd say or do anything to cozy up to whoever happened to be in power. Though I guess that could be said of most fascists ...