False Prophet

Meir Kahane's Legacy in Israel and America

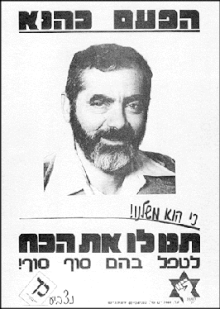

On Tuesday, a 57-year old named Reuven Kahane was arrested for hitting pro-Palestinian demonstrators with his car on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The first press to pick up the story were not New York City local papers or the American national outlets, but Israeli media. This is because Mr. Kahane is the cousin of a much more famous Kahane: extremist rabbi Meir Kahane, founder of the first party in the history of the Jewish state to be banned from the Knesset for racism. At the time of the ban in 1985, Kahane held the KACH party’s only seat—it barely got over the electoral threshold of one percent. Two years later he would be assassinated in New York by an Egyptian Islamist. But today the disciples of his apocalyptic vision hold an outsized influence in Israeli politics. Itamar Ben-Gvir, head of the neo-Kahanist Otzuma Yehudit party, Minister of National of Security, and key coalition partner of Benjamin Netanyahu, comes out of the Kach movement.

The story of Meir Kahane does not begin in Tel Aviv or Jerusalem or indeed Poland or Belarus, but Flatbush, Brooklyn, where he was born Martin David Kahane in 1932. His father, Charles, was an Orthodox Rabbi involved in the maximalist Revisionist Zionist movement. During Meir’s childhood, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, founder of Revisionism, was a family friend and houseguest of the Kahanes. As a teen, Meir joined the Betar, Revisionism’s paramilitary youth wing. In 1947, Kahane was arrested in New York for leading a group of other Betar youths in throwing eggs and tomatoes at the car of British Foreign Secreary Ernest Bevin for restricting Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine. Kahane would pursue a law degree and follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming a rabbi in the Howard Beach Jewish community in Queens.

In the 1950s and 60s, Kahane dabbled in politics: as an outspoken anticommunist he infiltrated the John Birch Society on behalf of the FBI. Then he wrote a pro-war tract The Jewish Stake in Vietnam, intended to convince American Jews that Vietnam was part of a global struggle against the same forces that threatened Israel. But it was in the fateful year of 1968 that he formed the Jewish Defense League in the wake of the New York teacher’s strike, when Albert Shanker’s United Federation of Teachers picketed attempts by parents and teachers to institute local control over the Oceansville-Brownsville school district. The strike pitted the largely Jewish teachers against Black and Hispanic parents, teachers, and administrations, featured antisemitic and racist provocations, and fractured the liberal coalition. Into one of the cracks slipped Kahane. The JDL styled itself as a community patrol to protect the lower middle class Jewish residents of Brooklyn from crime and antisemitic abuse. Kahane called for Jews to arm themselves. The group adopted the slogan “Never Again,” which also became the title of a 1971 book by Kahane.

Although Kahane’s politics were right wing, the JDL borrowed tactics from the radical left. His group opposed the Black Power movement, but mirrored its style. He adopted a fist over the star of David as an emblem, spoke of “Jewish Power,” JDL members even wore dark sunglasses like the Panthers. Kahane declared: “We have a reputation, spread by our enemies, that we are Jewish Panthers. Never deny it!” This brought him some admiration from the New Left. One New Left organizer said of the JDL, “I like their style, but abhor their politics.’” Abbie Hoffman is reputed to have remarked of Kahane, “I agree with his methods but not his goals.” And some Jewish New Left activists, disaffected with the New Left’s turn against Zionism as an agent of imperialism in the wake of the 1967 war, gravitated to Kahane’s movement.

It was not just against the New Left and Black radicals that Kahane turned his ire. As the scholar Shaul Magid puts it in his 2021 study of Kahane’s thought, “the real enemy for Kahane was Jewish liberalism.” The JDL idea was just as much a critique of the American liberal Jewish establishment, which he believed was out of touch, naive about the persistence of antisemitism, and, with its emphasis on assimilation, an existential threat to the continuation of Jewish identity: “When people think of Jewish defense, they automatically think of physical assault. And that’s not all we meant when we spoke of Jewish defense, he told the New York Times Magazine in 1971. “Jews of this country…face decimation through assimilation, intermarriage, alienation from their background and heritage. . . . I don’t think there is an ethnic group in this country that is more alienated from its background and heritage than Jews are.” There was also a populist component to this stance: Kahane opposed his coarser disciples to the suburban Jews in the “Scarsdales” and “Great Necks” whom he viewed with contempt. “Kahane’s early disciples were mostly not those who attended elite universities or the wealthier Jews of the Upper East or West Side of Manhattan or the suburbs, but the lower-middle-class youth of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx; many were children of Holocaust survivors who lived in troubled and racially mixed neighborhoods and often suffered from latent and overt anti-Semitism,” Magid writes.

In a provocative thesis, Magid even compares Kahane’s thought to the post-colonialism of thinkers like Frantz Fanon. To Kahane, even assimilated Jews are controlled or “colonized” by antisemitism in their desire to escape it, the Jewish adoption of violence is a not just a means to an end, but an active way of rejecting the rules and prerogatives of gentile society and forming a new Jewish subject, no longer emasculated and submissive, but powerful and assertive: “ Arguing that anti-Semitism was a kind of colonialism, trapping the Jew in a state of powerlessness and subjugation even as Jews in America may have prospered economically, Kahane offered a notion of violence as a liberating force.”

Although Kahane paid lip service to “democracy” and “the American dream,” he evidently despaired of the Jewish situation in America, probably because Jews were just too well-integrated. (The JDL had also moved from “defensive” actions and harassment to overt terrorism, creating a potentially uncomfortable legal situation for Kahane.) In 1971, he moved to Israel and set up shop as a radical there as well. Kahane attacked establishment Zionism from the right. The premise of Herzlian Zionism was that the establishment of a Jewish nation-state would normalize the Jews in relation to the other peoples of the world. But for Kahane, antisemitism is an permanent, ontological reality—a doctrine that Magid compares to Afro-Pessimism—a a fact of the world that can only be managed and defied, not defused. Likewise, Kahane pointed to the inherent contradiction of Israel attempting to be simultaneously a Jewish state and a liberal democracy. Either Israel is a Jewish state or a democracy it cannot be both: equal citizenship for its residents would mean the end of its Jewish character The attempt to offer non-Jews citizenship in the land of Israel is a hypocritical farce: it must be a theocratic state for Jews, Arabs must leave—”They must go” as he would entitle his 1980 book, which he wrote while serving time in jail for plotting to blow up the Dome of the Rock. He argued that while conventional Zionist labeled him a racist, they were the real racists, because his Zionism was rooted in the Jewish religion, not in a secular, European concept of ethnicity or peoplehood. And perversely much like Jabotinsky before him, his radicalism evinced more respect for the permanence of Arab nationalism than the moderates—”[We]—more than the Jewish leftists and liberals—understand and respect the reality of Arab nationalism, that we realize the futility of expecting the nationalist to give up his dream:”

No nationalist was ever bought by an indoor toilet and electricity in his home. And that is exactly what those who preach peace through materialism are doing. They are buying, or attempting to buy, the Arab nationalist and his love and pride in nationhood and state. Such an attempt is immoral and self-defeating. What the “moderates” and “compromisers” do not realize is that the Arab nationalist is as committed to his own people and to what he considers his own land as the Jews of Israel are to theirs. The Western colonialists who sincerely and honestly believed that they were benefiting the Asians and Africans whom they ruled, found that their arguments fell on deaf ears of native peoples who preferred poverty with independence to high living standards under foreign rule. Why should we expect Arabs to be different? Why should they not have the same pride that Israelis expect their children to have.

For him, the Jews should not be colonizers of a foreign people, but the sole sovereigns of Israel. The only solution therefore was segregation, war, expulsion.

Kahane and his KACH party labored at the margins of Israeli politics until 1984, when they broke through to capture a single seat in the Knesset. That body was alarmed by the intrusion of this rowdy member and passed an amendment to the Basic Law to specifically target Kahane. The “Racism Law,” as it would come to be known, resulted in the expulsion of Kahane from the Israeli parliament and the banning of his party.

Neither the ban on Kahane’s group nor his death have halted his movement. In 1994, a close disciple of Kahane, a settler named Baruch Goldstein, massacred 29 Palestinians praying at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. A 1994 poll found that almost 80 percent of Israelis decried Goldstein’s actions with only 3 percent viewing him positively. In 2023, a poll found that 10 percent of think of Goldstein as a national hero, with 57 percent seeing him as a terrorist—the rest are undecided. Before he entered the Knesset, Itamar Ben-Gvir had a photo of Goldstein in his living room.

In his response to Biden’s announcement of a weapons shipment freeze, Benjamin Netanyahu defiantly stated that Israel can “stand alone.” This is certainly bluster for domestic audiences, but it should give a moment’s pause how close this sounds Kahane’s apocalyptic ravings. For Kahane, the abnormality and uniqueness of the Jewish people would eventually require their going it alone. They had no true friends in the world. “Indeed, there are no allies and the United States itself will cut its bonds to Israel as its interests dictate. In the end, Zion and Zionism stand alone with the Almighty G-d who created them,” he wrote. There are many today, on both left and right, who, for different reasons, would respond to this, “Amen.”

"Abbie Hoffman is reputed to have remarked of Kahane, “I agree with his methods but not his goals.”"

This was especially witty, since it was an intentional inverted echo of a line from King's "Letter" that everyone knew at the time:

"I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action""

Magid’s sociological observations about Kahane’s JDL are on the money. His followers were troubled. And they had a lot to be troubled about. Jewish lower middle-class neighborhoods in the ’70s were emptying out and, in some cases, burning down. Those left behind were beleaguered.

Saw MK speak a couple of times when I was a teenager. He’d go on fund raising excursions, hitting up small business owners for contributions.

This was also a time of local school boards in the city controlling policy and patronage. Mayoral control of NYC schools didn’t come until much later.

On the Lower East Side there were brutal battles for control of the District 1 school board between Puerto Rican parents of the kids attending public school allied with left wing groups versus Jewish residents and the mostly Jewish, UFT (teacher’s union). School Board meetings sometimes descended into street fights involving local gangs. JDL members would attend meetings to protect Jewish school board members. The Department of Justice would send hundreds (no exaggeration) of observers to monitor the District 1 elections. Someone should write a book about the District 1 school board wars.