Foucault and the Conservatives

Biopolitics and American Gothic

(Note: I’m trying to stay off Twitter to focus on writing, but if you enjoy this please feel free to share it on social media.)

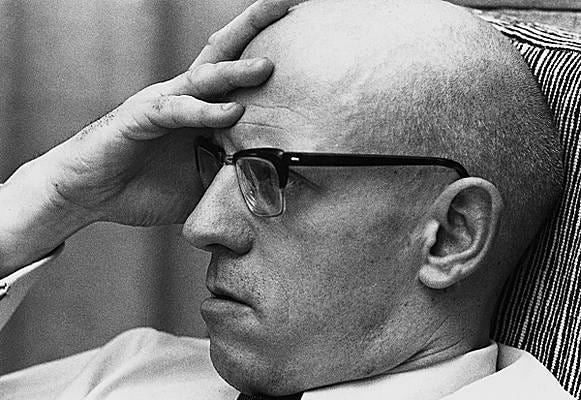

On May 25th, Ross Douthat had a column entitled “How Michel Foucault Lost the Left and Won the Right.” His argument is essentially that there’s a curious silence on the left about Michel Foucault’s notion of “biopolitics” in the age of Covid, and where there is interest in it, it’s on the right. We are told this is strange because biopower and biopolitics seem particularly well-suited to critique the regimes of population control erected during the pandemic. The explanation for the shift of interest in Foucault to the right is provided by the supposed dominance of the liberal order: They were once in a position of resistance and critique and now are in a position of control. Now, Foucault’s radical questioning of the objectivity of scientific knowledge is less germane to a project that wants us to “trust science”:

In turn, that makes his work useful to any movement at war with established “power-knowledge,” to use Foucauldian jargon, but dangerous and somewhat embarrassing once that movement finds itself responsible for the order of the world. And so the ideological shifts of the pandemic era, the Foucault realignment, tells us something significant about the balance of power in the West — where the cultural left increasingly understands itself as a new establishment of “power-knowledge,” requiring piety and loyalty more than accusation and critique.

This is most apparent with the debates over Covid-19. You could imagine a timeline in which the left was much more skeptical of experts, lockdowns and vaccine requirements — deploying Foucauldian categories to champion the individual’s bodily autonomy against the state’s system of control, defending popular skepticism against official knowledge, rejecting bureaucratic health management as just another mask for centralizing power

But Douthat ultimately calls Foucault “Satanic” and cautions against the temptation to use his “relativistic” tools against the liberal order. Douthat prefers that Old Time Religion.

I also have noticed an uptick in Conservative uses of “biopower” and “biopolitics",” due no doubt to the recent articles that Douthat cites. I tend to think these are more rhetorical than critical employments of the term, but I think it’s worth looking closely at Foucault’s notion of biopower and trying to understand what function it performs in Conservative discourse, to employ a slightly Foucauldian approach.

“Biopower”and “biopolitics” appear at the end of Volume I of Foucault’s The History of Sexuality. Foucault’s argument in that book is a striking overturning of common sense. The standard, modern narrative of sex and sexuality is that we were once repressed and now have become more liberated, free to talk about and have sex as we please. But Foucault enjoins us to reject “the hypothesis that modern industrial societies ushered in an age of increased sexual repression. We have not only witnessed a visible explosion of unorthodox sexualities; but-and this is the important point -a deployment quite different from the law, even if it is locally dependent on procedures of prohibition, has ensured, through a network of interconnecting mechanisms, the proliferation of specific pleasures and the multiplication of disparate sexualities.” The rules make the games we play; Structure precedes subject and agency.

This is all quite different from the stories both progressives and conservatives like to tell themselves about sex. “Sex positive” liberal people might blanch a little at this line: “We are often reminded of the countless procedures which Christianity once employed to make us detest the body; but let us ponder all the ruses that were employed for centuries to make us love sex, to make the knowledge of it desirable and everything said about it precious.” Yes, you too: You supposedly liberated free-spirits are just as produced by power as the buttoned-up squares.

“Biopower” and “biopolitics” describe the new sophisticated techniques of control that accompany and make possible this highly-articulated, complex modern society:

During the classical period, (nb: 17th-18th century) there was a rapid development of various disciplines -universities, secondary schools, barracks, workshops; there was also the emergence, in the field of political practices and economic observation, of the problems of birthrate, longevity, public health, housing, and migration. Hence there was an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations, marking the beginning of an era of "biopower.”

Previously, the sovereign had a relatively crude power over life and death, in the era of “biopower” the institutions of state and civil society foster and cultivate life with a “a power that exerts a positive influence on life, that endeavors to administer, optimize, and multiply it, subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations.” Foucault tells us, “This bio-power was without question an indispensable element in the development of capitalism; the latter would not , have been possible without the controlled insertion of bodies into the machinery of production and the adjustment of the phenomena of population to economic processes.” There are pretty clear references to totalitarianism, as well: “Wars are no longer waged in the name of a sovereign who must be defended; they are waged on behalf of the existence of everyone; entire populations are mobilized for the purpose of wholesale slaughter in the name of life necessity: massacres have become vital. It is as managers of life and survival, of bodies-and the race, that so many regimes have been able to wage so many wars, causing so many men to be killed.”

There’s something very compelling about this notion, but it’s worth asking if it’s actually historical. Did such a change actually occur or is it just the intensification of very old processes? All political orders address themselves to the productive, reproductive, and biological “bare lives” of their subjects in some way, even if the techniques have not always been so subtle and pervasive. Giorgio Agamben writes in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life that “the production of the biopolitical body is the original activity of sovereign power.” Whatever that might mean, it’s clear he doesn’t think it’s new.

I want to propose that what makes the Foucauldian “biopolitical” and “biopower” useful to today’s Conservatives is its quasi-historical dimension. It allows the following story to be told: Sure, once things were brutal, but they were direct and honest, now we have a regime of insidious and subtle control by people pretending to be good. This a variation on the myth of a lost Golden Age in the past that’s central in Conservative thinking. Relatedly, it allows for the evocation of an atmosphere of gloom that’s also dear to the Conservative mind. Foucault’s notion of “power” serves the purpose of general atmospherics well. It is infamously difficult to pin down, define, or localize: it seems to be an almost transcendental principle or even a living, vitalistic force of its own; the “biopower” pervades the entirety of society, it can be found everywhere. But on the Conservative account, it is being pumped into the air especially by those goddamn do-gooder liberal technocrats. In short, “biopolitics” can be made to fit in well with the standard rhetoric and cant of the Right.

Richard Rorty, complaining of the American left’s adoption of “theory ” and abandonment of politics, once called this view of power as a “temptation to Gothicize”:

Disengagement from practice produces theoretical hallucinations. These result in an intellectual environment which is, as Mark Edmundson says in his book Nightmare on Main Street, Gothic. The cultural Left is haunted by ubiquitous specters, the most frightening of which is called "power.” This is the name of what Edmundson calls Foucault's "haunting agency, which is everywhere and nowhere, as evanescent and insistent as a resourceful spook.

Rorty goes on to say, “The ubiquity of Foucauldian power is reminiscent of the ubiquity of Satan, and thus of the ubiquity of original sin that diabolical stain on every human soul.”

It’s questionable that this is an adequate or fair reading of Foucault, but it’s definitely a pretty decent interpretation of the way he’s used in American political discourse: fostering the imagination of a totally fearsome situation and the simultaneous abrogation of any responsibility or constructive action. Now the Right has adopted a new, sophisticated-sounding “spook” that can serve a number of different political and justificatory purposes. But, again, this Gothic imagination is a very old and natural territory for the Conservative mind; Indeed, it’s a kind of template for its thought in general:

A damsel (America) is locked in a dark, haunted castle, which was once a glorious palace in years gone by. Caretakers (liberal elites, the bureaucracy, academia) pretend to be benevolently working in the best interest of their charge, but they are actually sapping her vitality and keeping her weak and infirm with an evil spell (left-wing ideology, political correctness, egalitarianism, etc).

Some magic power will be required to break the spell, but Douthat cautions his readers against using the black magic of Foucault or Trumpism. I think it’s very telling that Russell Kirk, one of the intellectual godfathers of American Conservatism was himself an author of Gothic fiction.

I do think it’s worth retaining the notion of biopolitics, not as a vague atmosphere or charge against elite liberal perfidy but as a relatively coherent critical category. I believe it can be applied profitably to what Conservatives themselves hope to accomplish in power. One has to admit that concerns about the appropriate birthrate, migration, calling certain policies “pro-life,” worries about the relative masculinity and femininity of bodies and their need to be regulated down to the inspection of the genitalia are all “biopolitical” in the classic sense that Foucault defined it. One could go even further and speculate that the Conservative discourse that insisted that only weak or effete liberal elites needed to wear masks and work from home and that real, hardworking Americans wanted to get out there and do their jobs has a certain biopolitical flavor by way of its encouragement of part of the population to continue to engage in productive labor. The animating idea in all these cases is fostering and tending to a certain notion of healthy and desirable life, and this to occur in institutions all the way down, from the New York Times editorial page down to school athletics.

In point of fact, many of Douthat’s own columns are manifestly “biopolitical,” maybe a reason for his reluctance to have us look too closely at Foucault. On March 27th, Douthat frets about fertility in the column “How Does a Baby Bust End?” One week earlier he writes, “What the 2020s Need: Sex and Romance at the Movies”, saying “everyone should be rooting for the cinema of desire. For artistic reasons, yes — but also for the sake of the continuation of the human race.” Do I need to remind the reader of Foucault’s suggestion I cited earlier that we “ponder all the ruses that were employed for centuries to make us love sex, to make the knowledge of it desirable and everything said about it precious”?

No doubt there are just as many liberal and leftist practices and discourses that can be interpreted as equally biopolitical. The strength, and also the ultimate weakness, of such ideas is that they encourage us to see all-encompassing structures that shape the entirety of our thought and conduct. According to Foucault, we live in an era of biopolitics and we must all participate in its spirit to some degree or another. No one side is biopolitical, we are all biopolitical. But I’d suggest that we can still employ “biopolitics” and similar categories in a critical and humanistic way. This would have certainly not have pleased the arch anti-humanist Foucault, but I think these categories can promote reflection on the character of our collective thoughts and actions.

Whenever we are being treated as a “population” that needs tending to or a “race” that needs to be protected or controlled or “bodies” that have to be regulated or surveilled, we should begin to wonder about their dehumanizing and potentially disastrous consequences. We certainly have communal bonds and obligations to each other, but I think they operate in a much different way than some kind of meta-organism that requires each person to play some productive or reproductive functional part. That is when things get creepy and even a little bit totalitarian for me. It’s not always easy to draw the line or decide what is really taking place in a given situation, but continuing to think about biopolitics might sometimes provide us with a good place to start. And the truly provocative thing Foucault encourages us to do is to ask when what seems to be resistance to power is just another one of its effects.

This is a really good piece, John. I wonder if you'll have time to write more about how this intersects with contemporary essentialist attitudes on the right. I mean, they're historical attitudes but they're resurging as the more multiculti Star Trek-with-drone-strikes neocon movement is in retreat and the Britishized paleocons are continuing to advance, as are their politics of purification. It seems to me that there's some interaction between the notion that the libtards are using science as a stick to beat down the True American and the notion that the True American must protect his genetically European heritage; the latter seems like a far more direct and insidious mandate to protect the general welfare from interlopers than vaccine mandates, but maybe I don't grasp all the ins and outs.

I agree! I loved this piece. Also, I think you're right that Agamben is probably more correct than Foucault in his assertion that biopower has always been a constitutive feature of societies. Control over women's "chaos inducing" sexuality seems to have been pervasive since pre-modern times (Daniel Boyarin in "Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture" has some great readings on this point).

I think what you say here sums it up for me, "It’s not always easy to draw the line or decide what is really taking place in a given situation, but continuing to think about biopolitics might sometimes provide us with a good place to start." Anyone who tries to invoke "biopower" as some dispositive principle is probably not thinking in a very careful way about the current political scene. Reminds me of what you wrote about with the Arendt center with their invitation to the AFD politician. Invoking principles of free speech is mostly meaningless without good judgment.

Also John, where did Rorty write what you quoted?