Good Takes on Bad Discourse; Hindsight on 2020; The Age of Innocence

Reading, Watching 09.07.25

This is a regular feature for paid subscribers wherein I write a little bit about what I’ve been reading and/or watching.

If you’re not yet a paid subscriber but regularly read, enjoy, or share Unpopular Front, please consider signing up. This newsletter is completely reader-supported and represents my primary source of income. At 5 dollars a month, it’s less than most things at Starbucks, and it’s still less than the “recession special” at Gray’s Papaya — $7.50 for two hot dogs and a drink.

You can buy When the Clock Broke, now in paperback and available wherever books are sold. If you live in the UK, it’s also available there.

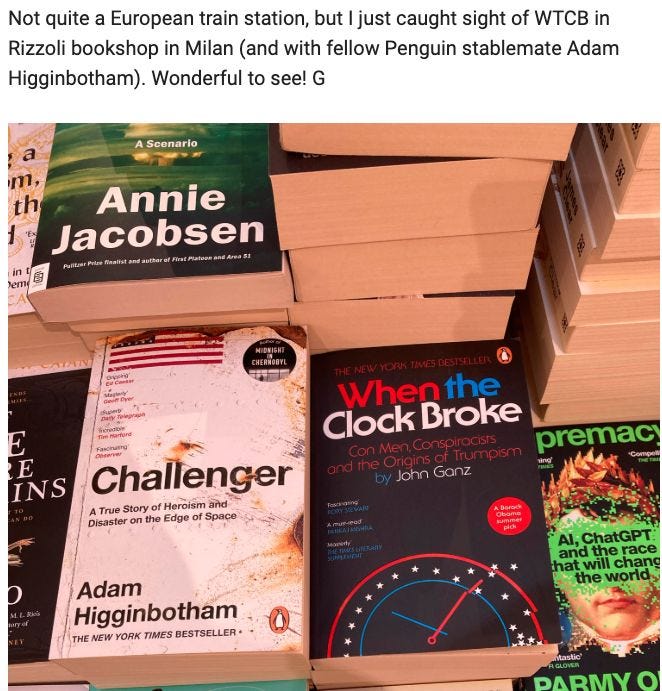

It’s also available in more and more places on the Continent. The book was recently sighted by my UK publisher at Rizzoli Bookstore in Milan. If you happen to see one in Europe, particularly in a train station bookstore, please do send me a pic!

In case you missed it, I appeared on Know Your Enemy pod to talk about Roman Polanski’s An Officer and a Spy.

For some reason, this week contains a lot of my fellow Substackers. Probably I’m going on the phone too much, but I’m glad I have in this case. This morning, I have for you:

William Hogeland on Thomas Chatterton Williams’s revisionist history of 2020.

The great B.D. McClay on the dreaded SS—that’s right: Sydney Sweeney.

Henry Begler on Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence.

Jack Hanson takes a crack at the overuse of “performative” in the culture.

But first, apropos of nothing, a quote from Robert Paxton’s Anatomy of Fascism:

The novelist Thomas Mann noted in his diary on March 27, 1933, two months after Hitler had become German chancellor, that he had witnessed a revolution of a kind never seen before, “without underlying ideas, against ideas, against everything nobler, better, decent, against freedom, truth and justice." The “common scum" had taken power, “accompanied by vast rejoicing on the part of the masses.”

And in his book The Birth of Fascist Ideology, Ze’ev Sternhell quotes Italian fascist intellectual Camillo Pellizzi in 1924, describing the goal as a “nonstate:”

For the moment, we conceive of the State neither as an association of individuals/citizens nor as a quasi-contract that would be fulfilled in the course of history. But if we have to describe this institution, we see it as the concretization of a predominant historical personality, as a social instrument usable for the realization of a myth. The state is thus not a fixed reality but a dynamic processthat cannot lay claim to movement unless, in another way, it is its own continuation. Nor can it be the renewal of a myth unless it represents the dialectical and tragic unity of previous myths.

This word “state” is inapplicable to our concept. In our nonstate, the law is dependent on the final myth, not the initial myth, and the final aim can only be, in its way, a new unity of previous myths.

Please read this piece on Thomas Chatterton Williams’s bad history from my FSG stablemate William Hogeland, a very good historian. A major stipulation of TCW’s recent book is that the January 6th insurrection was an outgrowth of the disorder of the George Floyd protests. But this requires reconfiguring events—there was already a far-right militia mobilization in the midst of the pandemic:

To support this equal-and-opposite-reaction (and/or outgrowth and/or mirroring) theory of right-wing violence against government, Williams alters the chronology of ‘20. It should be obvious that if violence migrated from left to right in the months following the summer protests of that year—if the January Sixth rioters really had been caught up in imitating the left when attacking the Capitol—if this whole post hoc ergo propter hoc setup had any real chance of credibility—then right-wing violence against government wouldn’t have preceded the George Floyd protests, and everyone knows it did. Williams himself knows. “While Trump and his supporters rebelled against [COVID] stay-at-home orders,” he says, “progressives found their own outlet for rebellion in the protest against police brutality.”

That first clause contradicts his thesis and makes his analysis incoherent, but the sentence, going on in a rush, mutes the effect. Maybe the reader is expected not to pause and consider it, or to take “rebelled” as merely figurative, not literal. If we unmute and slow down, we can easily recall that “rebelled against stay-at-home orders” meant direct action against government. A month before Floyd’s murder, in a stark precedent for January Sixth, armed paramilitary men expressing fury at the lockdown entered Michigan’s Capitol Building. Carrying weapons outside that building is legal; carrying weapons inside it isn’t, and the purpose of the entry, by both the armed and unarmed, was to intimidate not only the police but also Governor Whitmer.

Militia ferment against the governor was ongoing. About two weeks before the men entered the Capitol, Trump tweeted “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!” Thirteen members of a group calling itself Wolverine Watchmen, operating since early 2019, were plotting to kidnap Whitmer. It takes nothing but a superficial review of events to clarify that the Michigan rebels of April and May, whose actions and plans so closely prefigure the January Sixth action, weren’t reacting to or growing out of or imitating the rioting that a small minority of George Floyd protestors didn’t engage in until June, but it’s silly to have to review that chronology. Right-wing anti-government violence long preceded responses to both the COVID lockdowns and the Floyd killing. Do we really need to go painstakingly over the history of self-created right-wing paramilitary groups, going back at least to the ‘90’s, their string of standoffs with government, and their attitudes’ flowing climactically into Tump’s election in ‘16 and then into his failed reelection bid in ‘20?

I think this is an important point: Williams seems totally incurious, as many are, about the history of the paramilitary far right. The reaction is much deeper and older than he knows. As Hogeland notes, this is a long-standing movement, and the attack on the Capitol comes straight from its mythos and propaganda. Williams exhibits a familiar tic of centrist punditry: the tendency to blame every outrage on the right as the fault of the left. And to create an algorithm of simplified explanations, per Hogeland, Chatterton makes “a simple machine, operating according to the laws of a political pseudo-physics, designed to clean up messes by organizing conflict into predictable symmetries with no reference to life itself. If that approach represents the last, best hope of the liberal order, then the liberal order really might be doomed.”

I found the discourse around Sydney Sweeney to be both inane and demoralizing. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, consider yourself lucky. But Barbara McClay can get gold out of the dross of any pop culture phenomenon and does so again in her recent essay for The Lamp, which bears the terrific title “The Uggo Police:”

The “Ballad of Sydney Sweeney” goes like this: “They” wanted to exterminate beautiful busty blondes. “They” put ugly people in ads (sometimes). Now, however, here comes Sydney Sweeney, ending wokeness once and for all. The implication is that at some point in the past ten years, it’s been disadvantageous to be a curvaceous babe. The only sense in which that is true has not changed: Sweeney keeps showing up in ads in bras that don’t fit. But never mind that; thanks to Sweeney, it is now legal to be hot. The hot people have come out from the places where they’d been driven into hiding by the uggo police. Now they frolic freely in the sun. Very touching.

Meanwhile, the anti-Sweeney in this drama is Taylor Swift. Swift and Sweeney have been pitted against each other by spectators, including Donald Trump: Swift, who represents woke, is no longer hot; Sweeney, anti-woke, is hot. (Out with the old blonde, in with the new.) Like so many statements about both Taylor Swift and Sydney Sweeney, or, for that matter, by Trump, this one has no tether to reality, but it’s how a certain type of person wants things to be. There’s a level of personal betrayal at play here. Swift, who stays out of trouble, avoids politics, doesn’t do drugs, rarely seems out of control, and sings about love, was the crypto-conservative icon of an earlier era. Eventually, it turned out that she was not one of them. Their Brünnhilde was within another ring of fire. Now all their hopes are pinned on Sweeney.