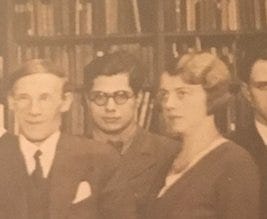

Gottfried Ballin (1914-1943)

Die Toten Mahnen

I had meant to jump directly into my series on the Third Republic, but since yesterday was Holocaust Remembrance Day I thought I would share a little about my cousin Gottfried Ballin.

The photo above is of a Stolperstein memorial for Gottfried in Köln. A Stolpersteine, literally “stumbling stones”, are set into the street in front of the houses and sometimes workplaces of people who were killed in the Holocaust. Gottfried was son of my grandfather’s aunt, Anna Ganz, so my cousin. But I didn’t know anything about Gottfried’s story until my friend and professor Silke- Maria Weineck looked up my family’s name a few years ago in the database of Stolpersteine and found him. For whatever reason, my grandfather Peter Ganz, who escaped Germany with his family in 1934, never mentioned him. As you might be able to figure out, the memorial says he was murdered in Auschwitz in 1943 (other sources give 1942, I’m not sure the reason for the discrepancy.) It also says he was arrested in 1934 for “high treason” and gives the names of three prisons where he was held.

Gottfried was a member of the SAPD, the German Socialist Workers Party, a left-wing group that split away from the SPD, the German Social Democratic Party in the early 1930s. From what I can understand (the scholarship on the group is in German and my ability to read German is nearly nonexistent) the SAP’s split was in response to the SPD’s lack of militancy in response to the creation of the Harzburg Front, the alliance of the Nazi party and other right wing parties and paramilitary groups. The SAPD apparently attracted an idealistic young cadre and, despite splintering from the SPD, agitated for an anti-fascist Popular Front strategy that would unite Social Democrats, Communists and the broader left against the Nazis. If you’re at all familiar with the history of Weimar, you’ll know that this wasn’t successful: the split between the Communists and the Social Democrats famously allowed the Nazis an opening. In any case, the SAPD’s membership was tiny; only about 15,000 members at its height, nothing near the mass support of the Social Democrats or Communists. (Willy Brandt, future chancellor of Germany, was an SAPD member in his youth .)

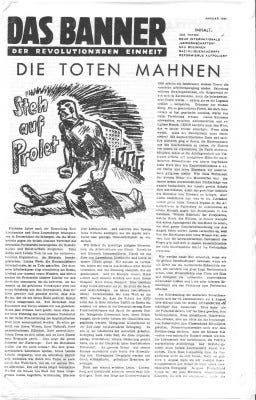

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, SAPD became very active in the illegal resistance to the regime. Unable to continue his studies because of Nazi race laws, my cousin Gottfried worked as an apprentice in our family’s bookstore in Köln, the Lengfeld’sche Buchhandlung, the oldest bookstore in the city, founded in 1842. He was also working in secret for the SAPD’s resistance efforts, along with the head of the clandestine group, Erich Sander, the son of the photographer August Sander, and his fiancée and future wife Helene Sälzer. SS street thugs ransacked the Ballin family house and retreated when they discovered his father Martin’s World War I medals, but not before they left anti-semitic graffiti on the facade of the house. In 1934, Gottfried and his entire group were arrested and charged with high treason. Gottfried’s particular crime was recruiting two members and distributing the SAPD newspaper, Das Banner. He was convicted and sentenced to a prison term. Apparently, he had hopes of being released at the end of the term because he was learning English with the plan to escape to South Africa. (There is a volume of his letters in prison to his mother and wife available in German.) Instead, he was deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1939 and then to Auschwitz, where he was killed after trying to escape in 1943. His mother Anna was deported to the Lodz ghetto in 1941, where it appears she died of an illness.

Right before the pandemic, I was about to go to Germany to meet a couple in Köln, Brigitte and Fritz Bilz, who collected Gottfried’s letters. They were publishing their book on the family bookstore in Köln and I was going to attend the book launch. Then COVID happened and I had to cancel my plans. Hopefully after the pandemic I will go. I also hope to translate their books at some point, or make Gottfried and my family in Köln the subject of my own work. One day, I’ll do a post on my grandfather’s escape story, which is also quite remarkable.

UPDATE: I spoke to Terence Renaud, a subscriber and historian who specializes in the interwar German left, this is what he told me:

My understanding is that a faction of leftwing SPD parliamentary deputies were expelled by the SPD leadership in 1931 for refusing to vote according to the party line. That faction opposed the party’s policy of toleration [Tolerierungspolitik] toward the centrist-conservative Brüning government. Such expulsions were a common disciplinary measure, but in the years leading up to 1933 they showed that the SPD leadership was losing touch with reality. So, upon being expelled, the faction rallied its journalist allies and thousands of rank-and-file workers (chiefly in Saxony) to create the SAP. The new party attracted further leftwing elements, including from the social democratic youth league (SAJ), the dissident communist KPO, and holdouts from the old Independent SPD (USPD). There were other individuals and groups that joined the SAP, too: between 1931 and 33, the splinter party used electoral means to try to build antifascist working-class unity outside the two major parties (SPD and KPD) and their affiliated unions. After Hitler’s takeover, a split formed within the SAP between a majority who wanted to dissolve back into the ranks of either the SPD or KPD and a diehard minority that wanted to continue the SAP’s separate existence and organize an antifascist underground apparatus. That active minority succeeded in its underground work and exile politics for a time, eventually cooperating with other leftwing splinter groups like Neu Beginnen and the Austrian Revolutionary Socialists … It’s true that the leftwing faction that created the SAP also opposed the SPD’s lack of militancy against rightwing and fascist formations including the Harzburg Front, as you say. Further leftwing elements broke from the SPD in July 1932 when the party & its union leaders refused to call a general strike in protest against the Nazi coup in the Prussian state government. Also in that year, in the so-called Berlin youth conflict, the SPD expelled a number of its youth leaders in the SAJ for preparing “illegal means” of resistance to fascism, ie, for building an underground apparat in the event of a fascist takeover. It’s dumbfounding how long SPD leaders persisted in thinking they could stick to parliamentary legality, even after Jan33, although they did send representatives into exile at that point (the Sopade, based initially in Prague).

Thank you John, Granny would have been very happy to read your article.

Hey man, I’m a professor of German and, if these aren’t handwritten, I’d be happy to translate some or help you translate them or whatever.