It's Jean-Marie's World, We're Just Living In It

The Legacies of Le Pen

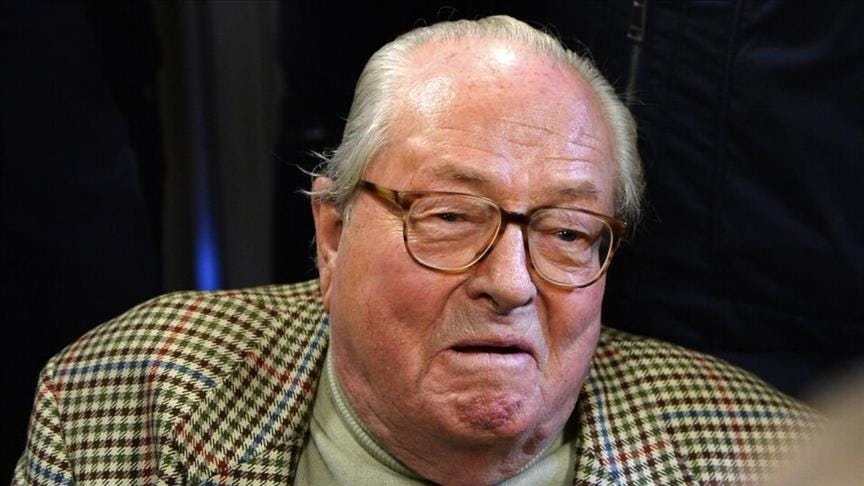

Yesterday, Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the Front national and godfather of the French far-right, died at age 96. For many, this was a moment of jubilation and I’m certainly among those who think the world is a better place without that vile ogre. Still, it’s hard to celebrate after reflecting that his political movement has gone from the margins to the mainstream, and the party that he founded, now led by his daughter Marine and renamed the Rassemblement national, is the single largest group in parliament and is on the cusp of power in France. His expulsion from the party by his daughter buoyed its fortunes and his death is likely only to out help more. Like many founders of movements, he will be more powerful in his absence.

Across the world, the type of politics Le Pen championed, a crude, combative populism that plays constantly at the edges of fascism, is becoming the dominant political style. It is a cliché to call things “the [insert nation] Trump” but Le Pen has some claim to being the French Trump avant la lettre: he pioneered the cheap machismo, vulgarity, casual racism, and outrageous declarations.

(For more depth than the obits, I recommend reading the always-excellent Arthur Goldhammer.)

The tradition Le Pen belonged to pre-dated and anticipated fascism—it has its roots in the previous century, in General Boulanger’s failed coup against the Third Republic and the anti-Dreyfusards’ violent, reactionary nationalism. The historian Michel Winock calls this tendency “national populism,” which I think is the best descriptor of Trump’s ideology, too. In his essay “The Return of National Populism,” Winock traces its roots:

The phenomenon appeared a century ago, between two well-known political crises, Boulangism and the Dreyfus affair (1887—1900). In those years, a new right took shape, challenging the official representatives of the Conservative party, making inroads into the following on the far left, and troubling the established political game by mobilizing the “masses” around a few slogans that were drummed into them. That new current was “populist.” It contrasted the people—their common sense and decency-to a political class corrupted and made soft by parliamentary pleasures. In response to the disorder and the “ crooks,” the people had to be given back their voice. Like Le Pen, who today recommends “ broadening the right of referendum,” Drumont, Rochefort, and the Boulangists challenged their equivalent o f the “ Gang of Four” with the vox populi. Maurice Barrés, the most distinguished interpreter of the trend, elaborated the theory of “ the instinct of the meek” against the “ logic” of intel lectuals. That right asserted it was “ social,” offering its protection to all the “little guys” against all the “fat cats.” Its public was primarily, but not exclusively, the old middle strata of artisans and tradespeople threatened by factories and department stores. The new right was able to rally the members of every profession uneasy about changes in the economic struc ture of the country. The Depression, the source of unemployment, which lasted until the last years of the century, was able to win it the sympathy of the unemployed, and the secular policy of the regime assured the adherence of numerous Catholics.

Winock identifies three moments, “three principal assertions” of the National Populist demagogue’s discourse: 1. We are in a state of decadence, 2. The guilty parties are known, and 3. Fortunately, Behold the savior. Look at the content of Le Pen’s xenophobic tirades back in the 1980s:

In Le Pen’s national populism, the Maghrebi immigrant has taken the place of the Jew, though heavy hints tend to demonstrate that the latter is not al ways exonerated. “ Everything comes from immigration; everything comes back to immigration.” Unemployment? “ Two and a half million unem ployed are two and a half million immigrants too many.” Criminality? The weekly newspaper of the National Front publishes a regular column on the misdeeds of the “invaders.” The demographic crisis? Foreigners are contributing to it by occupying public housing in the place of French people, who are thus discouraged from having children because of a lack of lodging. The imbalance in trade? The exportation of currency to im migrants’ countries of origin is the cause. And so on. Hence it follows that French “ natives” have “ the right of legitimate defense” against “ the surge of Asian and African populations.” Threatened with “ submersion,” we must react.

These assertions are repeated ad nauseam, until they are drilled into people:

The violent image, the inflammatory turn of phrase attracted more adherents than closely reasoned argument. National populism pioneered a technique of political propaganda that Gustave Le Bon, observer of the Boulangist movement and author of Psychologie desfoules (The crowd: A study of the popular mind, 1895), found striking: “Assertion pure and simple, disconnected from all reasoning and all proof, represents a sure means for instilling an idea in the popular mind. . . . In the end, the thing represented becomes encrusted in those deep regions of the unconscious where the motives of our actions develop.” And his pupil Le Pen echoes: “Politics is the art of saying and repeating things incessantly until they are understood and assimilated.”

Trump is also a great practitioner of the politics of “assertion pure and simple” and incessant repetition.

Winock writes, “Against the humanist tradition, national populism erects tribal egotism into a spiritual and political ideal. The obsession about ’race,’ the phobia about intermixing, the hatred of foreigners, are the usual expressions of that regression to the stage of closed society.” Is this not identical to the politics we see today in the United States?

For fifty years, the land of revolution and Liberté, égalité, fraternité put up a defense against Le Pen and his offspring, but now its republican traditions look weaker than ever.

Excellent historical context, we've had Trump types for a long time... And we should remember that France was actually ruled by French fascists in the Vichy years. When I visited in the 60s I got a Vichy franc coin in change one time. In place of the classic "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" it read "Work, Family, Fatherland" (Travaille, Famille, Patrie). It chilled me then and still does.

All that is solid melts into air, and while Marx may be right that this is necessary for the bourgeoisie, they certainly seem to hate it.