On Reading Criticism

Why I Like Literary Criticism

I’ve never been the most attentive reader of fiction. In fact, I’m not terribly well-read when it comes to novels. I’ve read some of the big classics; I especially like the 19th century, but I’ve never tried to exhaustively complete the canon and I have trouble keeping up with contemporary fiction. I find novels very rewarding when I do actually read them, but I still struggle to “get into” novels. Often I might like part of them, then set them aside. But one thing I notice that happens when you read a good novel is that the narrator inhabits your thoughts: your inner monologue begins to sound like the author. It comes almost as a relief to briefly borrow the consciousness of another. Even if that doesn’t quite happen, sometimes the novelist’s characters or the milieu and atmosphere they are describing is so compelling that you want to keep going; or you sympathize enough with their personal cause, even if it is selfish or destructive, that you want to see it through. Or, especially in 19th century fiction, the novelist may have sharp little aperçus about society and manners so you can enjoy participating in their incisive moral vision. There’s also the plot, but I am the least qualified to comment on that—I respond much more to atmosphere than story. I guess this all amounts to what old critics used to call “sympathetic imagination,” the ability to enter into the world of the novel, either through the voice of the narrator or the lives of its characters. If that doesn’t get activated for me, I have trouble finishing the book.

Somewhat embarrassingly then, most of my favorite authors are literary critics: Edmund Wilson, William Hazlitt, and Lionel Trilling. The book review, especially the slashing kind, was the type of writing I once aspired to master: I wanted to do something like Renata Adler’s brutal takedown of Pauline Kael in the New York Review of Books. I was even a little crestfallen when a professor I admired said that literary criticism wasn’t a very interesting genre of writing,—I happen to think it is a very interesting and revealing genre of writing.

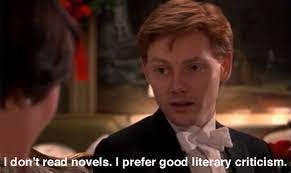

I have to admit that its interest for me probably lies in its being a little bit of a shortcut into the world literature. The image I chose above is from Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan, a charming comedy of manners where the young protagonist, Tom Townshend, is a bit of an outsider entering into society, in this case the world of debutante parties on the Upper East Side. This is a kind of miniaturization of the theme of many 19th century novels: a young man entering society and trying to find love or fortune or both. In this scene, he’s talking to his very earnest and intelligent love-interest Audrey about Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park and he reveals that he hasn’t read it, only Lionel Trilling’s essay on the novel. The dialogue goes like this:

Audrey Rouget : What Jane Austen novels have you read?

Tom Townsend : None. I don't read novels. I prefer good literary criticism. That way you get both the novelists' ideas as well as the critics' thinking. With fiction I can never forget that none of it really happened, that it's all just made up by the author.

This is of course funny and satiric because Tom is saying something quite pretentious and silly, but it’s also warm and endearing because he hasn’t learned to lie about what he’s read like most self-respecting adults. He very frankly admits this and reveals himself to be a quite sincere person, even if he’s putting on airs a little bit in another way. He’s a very unsophisticated sophisticate, still an innocent. But still, the point, if we can talk of such a thing, in this situation goes to Audrey, his interlocutor, who has actually read the books and has her own opinions; she is not simply mouthing the received notions of the critics in order to sound smart. Criticism is thought to be something secondary: reading novels is the really virtuous activity, but reading critics is the advanced move when you actually know what you are talking about and can form your own opinion on the critic’s interpretation.

I have also not read Mansfield Park, only Trilling’s essay on it. What he says there is very interesting. Basically, the heroine of the novel, Fanny Price, offends contemporary sensibilities because she is both highly virtuous and sickly. She does not confirm the modern piety, as Trilling calls it, that one should live a life that is stylish, vivacious, witty, imaginative, and romantically adventurous. The desired “complexity” of the modern personality is rejected. “[Mansfield Park’s] impulse is not to forgive but to condemn. Its praise is not for social freedom but for social stasis. It takes full notice of spiritedness, vivacity, celerity, and lightness, but only to reject them as being deterrents to the good life.” Trilling does not think this is a turn to dour sanctimony on Austen’s part so much as an “irony directed against irony itself.” Austen detects the possible falseness and insincerity endemic in the aesthetic creation of our personality and proposes a simpler, more direct form of life to counter it. Trilling’s praise of the novel ends up being pretty much unqualified.

Trilling writes that Austen is the first novelist “to be aware of the Terror which rules our situation, the ubiquitous anonymous judgment to which we respond, the necessity to feel to demonstrate the purity of our secular spirituality, whose dark and dubious places are more numerous and obscure than those of religious spirituality, to put our lives and styles to the question, making sure that not only in our deeds but in décor they exhibit the signs to the number of the secular-spiritual elect.” Neither are these outward signs of secular spirituality entirely about moral contents: they extend to an aesthetic judgment of the personality, a kind of snobbery about each aspect of people’s personal self-expression; it “requires us to judge not merely the moral act itself but also, and even more searchingly, the quality the agent.” Very provocatively, Trilling thinks Austen shares this understanding of the modern self with Hegel, who with his Aesthetics, “brought together the moral and aesthetic judgment. He did not in this in the old way of making morality the criterion of the aesthetic; on the contrary, he made the aesthetic the criterion of the moral.”

Trilling believes the placement of the personality and the constant judgment of its aesthetic-moral being at the center of life imposes a “terrible strain on us” that can result in the “disgust endemic in our culture.” Especially for those in creative professions, the requirement that one’s work and one’s self to form some kind of integrated moral-aesthetic whole is an acute and probably impossible demand.

The critic, who despite being “an agent of the Terror” like Austen, allows us to relieve this strain certain ways. I have to admit to being attracted to the air of authority and knowledge of the critics. It’s nice to have it all explained to you by someone who seems to know what they are talking about, who has read much more than you, has given it all such serious thought. The voice of the critic becomes the voice of a companion, of a factotum, of a kind of Virgil, of a guide, even of a friend, in the world of literature and the modern self. They are a narrator above the narrator. They have the inside dope. Often literally so: some of the best criticism is leavened with a bit of gossip, juicy little anecdotes about the author’s life, adding to the sense of talking with a friend. A really talented gossip, able to pithily sum up his target’s characters and pretensions, can sound like a good literary critic. And as Trilling says about irony in his Mansfield Park essay, there is something also a bit malicious in the fun of criticism, just as there is in gossip. We love to read the “takedown”, to see the puffed-up literary man or woman have his or her pretensions shown to be more vulgar than transcendent. This flatters our own sense of ourselves as competent and clearsighted judges of other persons and also makes their efforts at creation seem less transcendent and unattainable if we are shown their failures.

Trilling thinks the spirit of deflation, if not exactly satire or travesty, is also shared by novels. In his essay on Manners, Morals, and the Novel, he defines what’s accomplished in the best novels:

The characteristic work of the novel is to record the illusion that snobbery generates and try to penetrate to the truth which, as the novel assumes lies hidden beneath all false appearances. Money, snobbery, the ideal of status, these become in themselves the objects of fantasy, the support of the fantasies of love, freedom, charm, power as in Madame Bovary, whose heroine is the sister, at a three-centuries remove, of Don Quixote. The greatness of Great Expectations begins in its title: modern society bases itself on great expectations which, if they are realized, are found to exist by reason of a sordid, hidden reality.

The author is framed here as observer and indeed critic of the follies of the imagination. But they require and foster those follies as well: their work is imaginative and for their characters to be alive they must have expectations, great or sordid, hopes to accomplish some goal, pretensions to a life of greatness or beauty or moral rectitude that cannot quite be lived up to. François Truffaut once said that war movies couldn’t be truly anti-war because they always made it look too glamorous. In similar manner, I think all good novels make even the shallowest pursuits seem to have the shimmer of spiritual life. The most incisive criticism of society relies on disillusionment, but the more grand the preexisting illusion the more dramatic and satisfying the effect of its being disabused.

The author’s work, attempting to jump outside one’s society into a realm of higher self-consciousness, has its dangers: the pursuit of moral or intellectual superiority can hazard the soul just as much, if not more, than the pursuit of fame or money. The price of a failure in this regard is often ridicule at the hands of the displeased critic. The critic reminds us that the authors are only human: they are very much characters, too, beset by their own fantasies and pretensions, some of which hopefully are interesting or revealing or characteristic of the age. The authors themselves often form the prototypes of certain moral selves that eventually come to proliferate in a society; their original creative activity of self-formation becomes emulated, even unconsciously, by the culture at large. The Byronic hero, desperate and stormy in his labile affections and adventures, became a model for the 19th century, so much so that even writers who made use of the archetype felt the need to comment sardonically on it, as Alexander Pushkin, indulging in a little bit of literary criticism of his own, does here in Eugene Onegin:

We also have Byron’s contemporary and acquaintance William Hazlitt, to deflate the Byronic myth as soon as it began, as he does with his characteristic incision and wit in his The Spirit of the Age:

You get the sense Hazlitt has really got his number. Even if its an incisive critique of the man and his imaginative efforts, it’s also generous in its terms: Byron, as a noble born poet, sort of could not be any other way. There is a touch of fate being fulfilled here. This is almost too easy: Byron is the model example of the perils of out-of-control pretension and conceit. Little shades of this form of life certainly still flit around our society. Just look at Leigh Hunt, another critic who spent time with Byron in Italy, has to say about Byron’s attachments to women and we can still certainly recognize this type of man all too easily: “The truth is, as I have said before, that he had never known any thing of love but the animal passion. His poetry had given this gracefuller aspect, when young:—he could believe in the passion of Romeo and Juliet. But the moment he thought he had attained to years of discretion, what with the help of bad companions, and sense of his own merits for want of comparison to check it, he had made the wise and blessed discovery that women might love himself though he could not return the passion; and that all women’s love, the very best of it, was nothing but vanity.”

Still, as Hunt points out, Byron and the figures of poetry are not quite the same; they are an idealized version of his actual self, which was somewhat more awkward than his imaginings: “He took care also to give them a great quantity of what he was singularly deficient in,—which was self-possession, for when it is added, that he had no address, even in the ordinary sense of the word,—that he hummed and hawed, and looked confused, on very trivial occasions,—that he could much have more easily get into a dilemma than out of it…” Lord Byron, who crafted his life as a work of art, has certainly come in for harsh judgment from the Terror of the critics. We modern Jacobins certainly no longer suffer his sort of privilege.

Every so often it seems the literary and cultural world issues a new broadside attempts to decree that certain aesthetic attitudes are good while others are bad. Usually this attitude is “irony:” either we decide there’s too much of or too little of it we demand for it to be stamped out to create a new birth of sincerity or that people have become much too earnest and we need a new efflorescence of irony to allow the artistic imagination its proper space of freedom and sovereignty. I think Trilling in his Mansfield Park essay puts it perfectly, when he writes, “Most people either value irony too much or fear it too much.” It also seems this periodic demand for or rejection of irony extends to the very beginning of modernity. In Hegel’s lectures on aesthetics, given just a few years after the publication of Mansfield Park, the philosopher becomes very cross with the Romantic poets of his era who set up irony as a principle of life as well as an aesthetic criterion:

…this virtuosity of an ironical artistic life apprehends itself as a divine creative genius for which anything and everything is only an unsubstantial creature, to which the creator, knowing himself to be disengaged and free from everything, is not bound, because he is just as able to destroy it as to create it. In that case, he who has reached this standpoint of divine genius looks down from his high rank on all other men, for they are pronounced dull and limited, inasmuch as law, morals, etc., still count for them as fixed, essential, and obligatory. So then the individual, who lives in this way as an artist, does give himself relations to others: he lives with friends, mistresses, etc. ; but, by his being a genius, this relation to his own specific reality, his particular actions, as well as to what is absolute and universal, is at the same time null; his attitude to it all is ironical.

Hegel thinks this ironic, aestheticized attitude just avoids all substantial and serious content of art and the self and ends up undermining itself:

But the ironical, as the individuality of genius, lies in the self-destruction of the noble, great, and excellent; and so the objective art-formations too will have to display only the principle of absolute subjectivity, by showing forth what has worth and dignity for mankind as null in its self-destruction. This then implies that not only is there to be no seriousness about law, morals, and truth, but that there is nothing in what is lofty and best, since, in its appearance in individuals, characters, and actions, it contradicts and destroys itself and so is ironical about itself.

Hegel thinks works created under this standard lose their interest for us, because they have no actual content. And the poet’s complaints about the philistinism of his audience are totally out of order, since his work is empty. “Such representations can awaken no genuine interest, “ he writes. “For this reason, after all, on the part of irony there are steady complaints about the public's deficiency in profound sensibility, artistic insight, and genius, because it does not understand this loftiness of irony; i.e. the public does not enjoy this mediocrity and what is partly wishy-washy, partly characterless.”

Hegel is obviously dealing with a very radical, very German variant of the ironic attitude: an extremism that turns an aesthetic principle into an entire form of life. But one can recognize the hints of this sentiment even in more attenuated forms. Hegel calls the resulting creature, the victim of the fashion for irony, a “morbid beautiful soul” and here we can see clearly the combination of aesthetic and moral assessment that Trilling talked about. The moral and aesthetic lack are synthesized in a certain type of deficient self. Tellingly, Hegel elsewhere applies this ironic appellation (the beautiful soul isn’t really beautiful) to a certain type of moral agent that is caught up in the purity of her own intentions and believes she is better than everyone else. For Hegel, irony and moral self-righteousness are not opposed forms of self-creation, but are profoundly identical. They both run on an unsustainable, puritanical egotism: one thinks everyone else (except members of the elect chosen precisely to reflect oneself) is a species of dowdy, literal-minded fool, for the other everyone else is corrupt and wicked. Neither the pretension to a wholly ironical, aesthetic nor a sanctimonious, moral ego can provide an escape hatch from the crucible of the modern self,—striking such poses only makes things worse.

Hegel tantalizingly mentions in this passage the possibility of “a truly beautiful soul,” but all he says is that it “acts and is actual.” Presumably, this means that to be a real beautiful soul, one has to do engage with the real world and its contents in some way, and cannot either take refuge in the realm of aesthetic distance or unmixed moral purity. The fact of the matter is that no imaginary self we create and project can fully account for the judgments of the world. There is no guarantee that our actions or even our sense of self will succeed. Indeed, it is guaranteed that they will fail. The world’s judgment of these efforts is likely to be ironic and disappoint our expectations: when we set ourselves up be exclusively moral beings, our egotistical self-interest is likely to be discovered not far off, and if we try to think of ourselves and others in exclusively aesthetic terms, the impulse to legislate morally returns, now disguised as snobbery. The Terror of the modern self is always able to discover—or invent—“the true motive.” Our only hope then is to be met with a sympathetic judge—a fair critic.

I once had a creative writing student who had real talent, I told him he should buckle down and write his stories all the way through. He told me that he felt he needed to read more post-structuralism before he could properly write the fiction he wanted to put out in the world. My colleagues laughed at the folly of youth in that student’s statement, but I was happy to see it for what it was: He was simply a budding Critic, capital C. His mind was prone to seeking patterns, structures, considerations of machinations... We are misled by our choice of language in what’s called “lit crit”, as it gets reified as something ancillary. It’s simply a qualitatively unique mode of thinking and expression, and every bit as generative as the creative works with which it corresponds. We don’t call the traditional male dancer in a Tango couple the “dancing critic”. They are very much in it together.

This helps me realize that I value attention to the specific words of the text as much as I do the "subject matter" discourse in criticism. I once claimed to value the words more, but that's silly aestheticizing. Yet reading this, even though I don't really care for Byron, the phrase "tenth transmitter of a foolish face" just leaps off the screen as a beautifully Augustan bit of concision. So give me Empson at his best over even these excellent critic-writers.