Philip Guston, Lead Belly, and “Woke” Art

Thinking About Two WPA Artists Today

While doing research for an eventual post on “wokeness,” I learned something interesting: It turns out one of the earliest documented uses of the word “woke,” in the modern sense of being socially or politically aware, comes from a Lead Belly recording of his song about the Scottsboro Boys. Speaking to folklorist Alan Lomax at the end of the recording, the legendary Louisianian blues and folk singer can be heard saying, “I advise everybody, be a little careful when they go along through there—best stay woke, keep their eyes open.”

The Scottsboro Boys were nine black teenagers accused of raping two white women in Alabama in the 1930s. The entire group was convicted and sentenced to death on scant evidence. The case became a national scandal, rallying progressives and leftists to the cause of the young men, with the Communist Party and the N.A.A.C.P. organizing public drives for their defense. Many artists who moved in radical circles, including Lead Belly, a friend of the novelist Richard Wright, who was then Harlem editor of the Communist Daily Worker, responded with works of protest. Lead Belly, who also wrote other Popular Front-inflected songs against fascism and Jim Crow, like “Bourgeois Blues” and “Mr. Hitler,” premiered his song at a Federal Writer’s Project event. (The F.W.P. was part of the Works Progress Administration, the New Deal organization that gave jobs to the unemployed.)

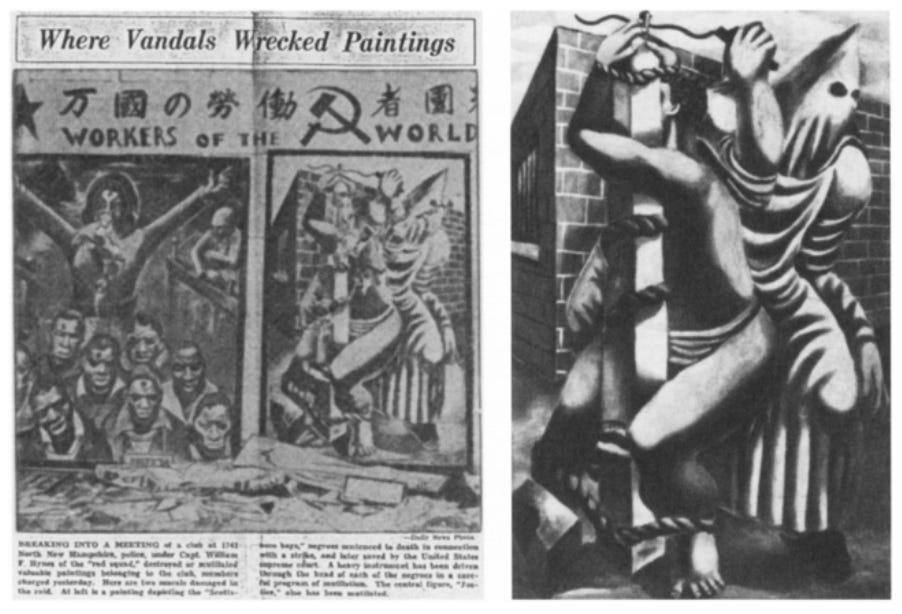

This struck me, because one of my favorite painters, Philip Guston, also made a work responding to the Scottsboro case. Guston, then still known as Goldstein, was a young art student living in Los Angeles. He and a friend, Reuben Kadish, made a series of murals for the walls of the Marxist John Reed Club. Kadish’s represented the Scottboro boys; Guston’s mural depicted a black man being flogged by a hooded Klansman figure. The police’s Red Squad attacked the John Reed Club and vandalized the paintings, even using them for target practice. In his recollections on the matter, Guston directly named the K.K.K. as the perpetrator.

There’s good reason not to sharply delineate the cops and the Klan. The Ku Klux Klan had a large presence in L.A. at the time and had infiltrated the police forces. In the 1940s, the chief of the Culver City police was accused of openly recruiting for the Klan in office.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Guston left figuration and political messages behind, becoming one of the leading Abstract Expressionist painters, although he retained a certain idiosyncrasy, a tentativeness and pensiveness, that sets his work apart from the gestural heroics of other painters of that school.

But in the late 1960s, Guston said the violence of the anti-war protests caused him to be “flooded by a memory” of the Scottsboro murals and their vandalism. Figuration began to return to Guston’s work, including the Klan figures, now represented in a strange, cartoonish style that takes as much from Krazy Kat comics as the tradition of European painting from Piero della Francesco to De Chirico. “I started conceiving an imaginary city being overtaken by the Klan,” the painter recalled.

In a way, one could even say there was something reminiscent of the down-to-earth, popular style of Lead Belly’s folk song in Guston’s new body of work. (Like Lead Belly, Guston for a time did work for the W.P.A.) The critics responded harshly to his abandonment of high abstraction in favor of newfound folksiness. The New York Times’ Hilton Kramer accused Guston of being a “mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum,” a high-cultural sophisticate now possessed of vulgar pretensions. “We are asked to take seriously his new persona as an urban primitive, and this is asking too much.” As Robert Hughes wrote, Kramer dismissed the work “as a mere exercise in radical chic.”

Although his late pictures are now canonized as some of the most important American painting of the second half of the 20th century, Guston’s work has not lost its ability to unsettle. You might remember in the wake of the George Floyd killing and the national protests against police brutality, a Guston retrospective to be shown at four major museums was postponed until 2024 because of the Klan imagery, leading to its own protest from a number of artists and writers. Now, after the protest, the show will be put on in 2022, with added contextual work by other artists and historians. (I’m not sure what other works the curators have planned for the context for the revamped Guston show, but I think Lead Belly’s recording and other works that responded to the Scottsboro incident would probably be good to include.)

It would be too easy—and also not entirely honest—to lean on Guston’s early credentials as a radical protest artist to defend this body of work as being politically correct. First of all, I think the work needs no such defense. Second, I think it elides the complicated nature of these pictures. Guston shockingly described his Klan figures as self-portraits:

This was the beginning. They are self-portraits. I perceive myself as being behind a hood. In the new series of "hoods" my attempt was really not to illustrate, to do pictures of the KKK, as I had done earlier. The idea of evil fascinated me, and rather like Isaac Babel who had joined the Cossacks, lived with them and written stories about them, I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil? To plan and plot…Then I started thinking that in this city, in which creatures or insects had taken over, or were running the world, there were bound to be artists. What would they paint? They would paint each other, or paint self-portraits. I did a whole series in which I made a spoof of the whole art world. I had hoods looking at field paintings, hoods being at art openings, hoods having discussions about colour. I had a good time.

Guston, himself of Ukrainian Jewish origin and for whom the Cossack would’ve been a palpable and terrifying family memory, presents himself here as complicit and even identified with these evil figures. He used them to satirize himself and the entire art world. It’s been theorized that Guston’s Klan figures came from his own guilt over his father’s suicide, but I wonder if they had something to do with the guilt of having given up political and engaged art for the “pure” aesthetics of abstraction in the 1950s. Did Guston feel he had abandoned an important moral and political dimension of his work for critical and commercial success? It all came back to him with the shock of the 1960s, but as a mature artist he did not return directly back into protest work and instead a created a body of work that was both more opaque but also more personally risky and revealing. It would’ve been the move of a lesser artist to return to straightforwardly to political themes at a time when they were salient. In any case, the judgment at the time of critic Robert Hughes seems almost exactly wrong: “As political statement, they are all as simple-minded as the bigotry they denounce.” (To be fair, Hughes later repented of this pronouncement, but it’s interesting to note at the time they were viewed as being too bluntly political, too “woke”, if you’ll permit me.)

Although Kramer’s assessment was wrong, in general today we accept its type of judgment as almost an article of common sense: artists who attempt to recapture sincerity and directness of either their childhood themes or the common folk are engaging in a type of pretense that’s not be trusted; it is thought to be a form of artistic self-dealing, a violation of class boundaries thats either patently inauthentic if not actually exploitative. But maybe we should risk seeing something almost pre-political and naive, not just post-political, ironic, and self-satirizing, about Guston’s late efforts. Or to wonder if those modes can even be meaningfully separated. Vico in his cyclical theory of history posits an underlying identity between humanity’s harsh, primitive origins and its overly-sophisticated, ironic late stages, where people “under soft words and embraces, plot against the fortunes of friends and intimates;” or, to use Guston’s phrase, they “plot and plan.” Vico called this the “barbarism of reflection” and wrote it would turn humanity’s cities into forest and caves again. In the same interview I quoted above, Guston likened this body of work to “cave painting,” almost as if he was just documenting something experienced in the L.A. of his youth, his close encounter with the beasts of the Klan, remarking “they call it art afterwards, you know.” We have yet to finally figure out the meaning of all these markings, but like Lead Belly said of his song, one lesson might just be “keep your eyes open.”

I like this article a lot. Two thoughts :

On Lead Belly and "woke" : it seems to me that for all the criticism of "wokeness" and its excesses, real or imagined, this early understanding of "woke" has never been seriously challenged, and that this may be because it's about something real and so important ?

(since Harlem and communist papers were mentioned : have you by any chance read some Claude McKay ?)

On Philip Guston : I'm not entirely sure on how to read your analysis ; I take it as positive, though the Vico quotations make it look somewhat critical. But that may be simply Vico's style. As far as I'm concerned, on gut level, I find that there's a direct child-like honesty to the latter Klan paintings that naturally pushes aside the "clever irony" interpretation. The figures are strange, cute, and dangerous (they're splattered with blood, unless it is red paint ?). Reading the quotation on Isaac Babel, one is reminded of the common childhood urge to tame the scariest monsters ("what if I could hide among the monsters ? What if the monsters were my friends ?") If these figures are forming an art world, one is led to think that Philip Guston was "woke" in the Lead Belly sense, and noticed that something was off with the art world in which he was evolving. Checking the whole of the University of Minnesota 1978 talk, where the quotation comes from, seems to support this interpretation : Guston tells about how abstract expressionism, in which he had believed, seemed to him to have exhausted its possibilities, with paintings being buried under the expected discourse of a whole coterie and not managing to speak for themselves nor to surprise anymore. To remain faithful to the truth of his medium, he had to tap into something else in him, and the scary Klan figures of his youth as well as the imaginary cities he was seeing while driving toward New York provided him with it (Perhaps the Klan figures were also a reference to a similar exhaustion of his militant painting phase ?) So yes, the Vico idea of a new primitive innocence that draws from the sophistication that came before seems to be accurate. I like this quote from the Guston talk : "It's a long, long preparation for a few moments of innocence."

To fall back on the beginning of the article, it seems to me this idea of exhaustion and renewal can also apply to "wokeness". One of the few valid criticisms of it was that what is important about this perspective had often ended up being buried under expected, cliched discourse. It seems to me that the reaction to the Trump administration's gross attacks is leading to a renewal in the way of defending it, with more shared commitment and a different, more subtle discourse.