Poe's Sci-Fi; Lord Byron and the Luddites; Visconti's ‘Conversation Piece’

Reading Watching 02.09.26

This is a regular feature for paid subscribers wherein I write a little bit about what I’ve been reading and/or watching.

If you’re not yet a paid subscriber but regularly read, enjoy, or share Unpopular Front, please consider signing up. This newsletter is completely reader-supported and represents my primary source of income. At 5 dollars a month, it’s less than most things at Starbucks.

When the Clock Broke is now out in paperback and available wherever books are sold. If you live in the UK, it’s also available there. The UK edition is also apparently available all over the world, too! I’ve received reports now of book sightings in places as far as Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and Christchurch, New Zealand. It seems relatively easy to find in Commonwealth countries and at English-language bookstores abroad.

I also do a film podcast with Jamelle Bouie of The New York Times. On our Patreon, we have a lot of bonus content, including a weekly politics discussion.

I forgot to share it at the. time, but a couple of weeks ago I did an interview with Marshall Pierce for Jacobin about Trump’s imperialist foreign policy and the possible crack-up of the Trump coalition. Since the interview, several polls have come out that show Trump struggling with white working-class voters, a group once supposed to be the core of his support. In fact, he’s facing a collapse of support among working-class voters from all demographics. It was cut from the final text, but I pointed out that those voters were the group most hostile to A.I. I think that a left-wing populist strategy should capitalize on the connection between Silicon Valley’s pivot to arms tech and Trump’s betrayal of his “isolationist” promises.

For America’s upcoming 250th anniversary, I was asked by the Wall Street Journal to write about an early American author who was important to me. I picked Edgar Allan Poe:

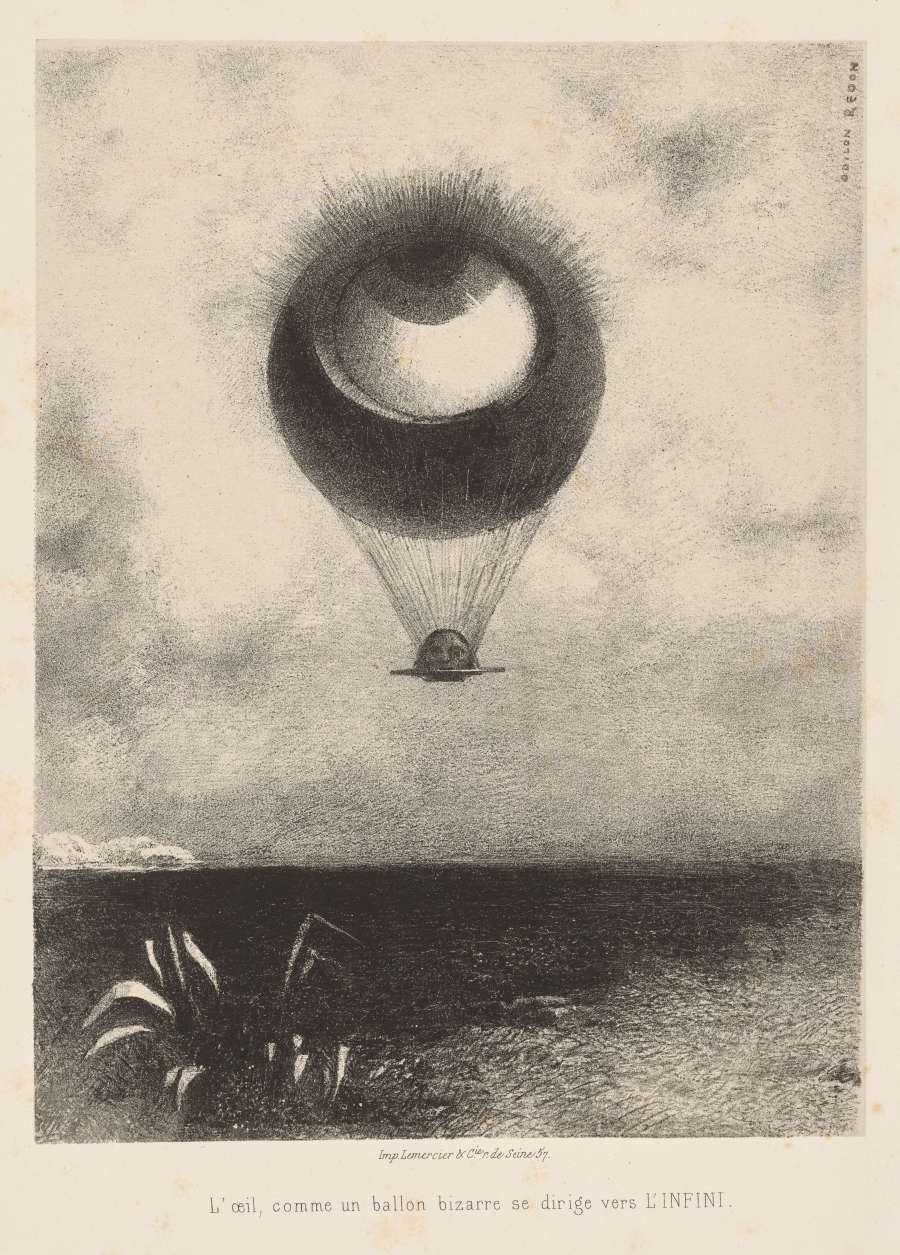

Edgar Allan Poe made me want to be a writer. I was about 12 years old on a family vacation to Italy when I found a Penguin Classic at the Anglo-American Bookstore in Rome called “The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe.” The cover featured a lithograph by Odilon Redon of an enormous eye in the shape of a hot-air balloon, a piece that apparently was inspired by Poe. (He was the first of the many American artistic oddballs that the French especially took to.)

The collection contained 16 “stories,” some of which pushed the limits of what could be called fiction. One was an intentional hoax that Poe had tried to peddle in a newspaper about a balloon reaching the moon; another was his visionary essay on the origins of the universe; there was a philosophical dialogue between two souls in the afterlife on the nature of death.

Then there was the style, with all its arabesque flourishes and ornate detail. It felt like there was something arch, ironic and archaic about it even for its own era. It was serious about the intellect but also playful, imaginative. I didn’t realize it at the time, but there was also insecurity there: An American embarrassed by a rough, unsophisticated America, envious of Europe’s aristocratic polish. In short, it was perfect for an adolescent boy of burgeoning but unformed pretensions. I tried to copy it, unsuccessfully, if you take my teacher’s response to my own story about a hot-air balloon as any indication. I hardly ever read or even think about Poe anymore, but I suppose those stories first directed my mind’s eye toward infinity.

I was looking at the book again after many years and realized it had probably also gotten me interested in intellectual history and the history of ideas. Harold Beaver's introduction describes how early 19th-century electrochemistry inspired Poe. I also wonder now, too, if it shaped my mixed feelings about science and technology, my simultaneous attraction and fear of those things. From Beaver’s intro:

Something of this ambivalence, ever since, has haunted science fiction. Itself an offshoot of gothicism, the new genre was to evoke a horror both of the future and of the science which could bring that future about. By identifying with the collapse of technology, it was already critically undermining that technology. Yet its only appeal was to science. It had nowhere to turn but to science for its salvation. The fiction, then, was that somehow science must learn to control its own disastrous career. Poe too – quite self-consciously, of course – was working in this gothic vein. Within his husk of mathematics, as often as not, lurks an old-fashioned kernel of magic. In a sense, he recreated all the traditional feats of magic in pseudo-scientific terms (of galvanism and mesmerism). Alchemy became the synthetic manufacture of 'Von Kempelen and His Discovery'; resurrection of the dead, the time travel of 'Some Words with a Mummy'; demonic possession, the hypnotic or 'magnetic relation' of 'A Tale of the Ragged Mountains'; apocalyptic vision, the cataclysmic fire of 'The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion.' Just as the pseudo-scholarship (in antiquarian statutes and genealogies) of Scott, or gothic elaboration of Hawthorne, was part of an attempt to make the imaginative spell more potent, more binding, so Poe's detailed and mathematical science intensifies his imaginative fusion with the occult.

Probably a lot to think about now in the burgeoning AI age, which has its own gothic foreboding and seems to confirm our fears of ghosts in the machines, and also, it must be noted, comes with its own hoaxes.