Die Toten Mahnen

The Dead Admonish

This is going to be a little different than my usual digest of the week’s books and movies. On Friday, I received a letter from the German consulate in New York that my application for restoration of citizenship had been accepted. I was also invited to a naturalization ceremony at the house of the consul general along with “others whose families were stripped of German citizenship by the Nazi regime.” This process has taken a very long time: I believe I first applied back in 2018. The pandemic slowed things down even more, because I couldn’t get some requisite documents from the U.S. State Department. After such a long wait, and having to go track down and submit documents, this is obviously very satisfying. I’m going to spend this newsletter reflecting a little on what this whole process has meant.

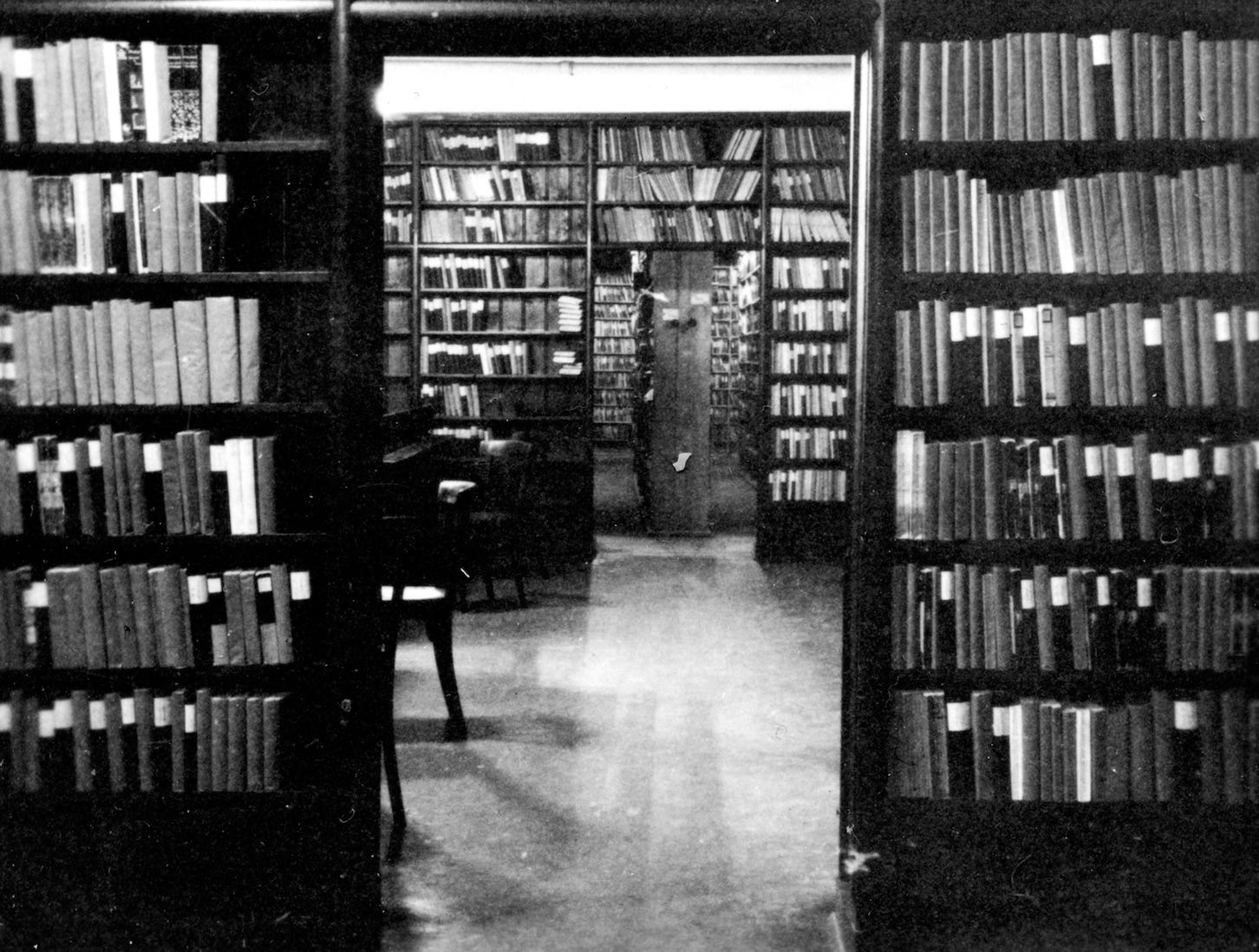

Around the time I first submitted my application—I can’t remember now if it was after or if it was the reason I finally decided to start the process—I learned of a relative Gottfried Ballin who was killed in Auschwitz. My professor from University of Michigan, Silke-Maria Weineck, found a Stolperstein memorial for him in Köln, the city where my family lived. Stolpersteine, literally “stumbling stones,” are set into the street in front of the houses and sometimes workplaces of people who were killed in the Holocaust. It turned out that Gottfried was the son of my grandfather’s aunt, Anna Ganz, so his and my cousin. My grandfather, Peter Ganz, never mentioned his cousin, despite the fact that Gottfried worked at the bookstore my family owned in Köln.

As you can see on his Stolperstein it reads “Verhaftet 1934 ‘Vorbereitung zum Hochverrat.’” This means “Arrested 1934 ‘Preparation for High Treason’.” I discovered Gottfried had been a member of an illegal antifascist resistance cell. Here is Gottfried’s biography as far as I’ve been able to reconstruct it:

Gottfried was born in 1914 to Anna Ballin and Martin Ballin on April 9 1914. Anna, a painting student, was the daughter of Alexander Ganz (my great great grandfather,) the proprietor of the Lengfeld’sche Buchhandlung, the oldest and “most renowned” bookstore in Köln and Martin was a doctor from a Lithuanian Jewish background. Martin Ballin served with distinction in the First World War, was decorated for bravery, but returned “mentally and physically broken” and committed suicide in 1919. Gottfried and his brothers, Wolfgang and Arnold, lived with their mother. It appears Nazi-era restrictions prevented Gottfried, who had a deep interest in literature, from pursuing higher education after graduating high school, so he went to work as an apprentice at the family bookstore. Unlike the rest of the family, who were apparently content with their cultured upper-middle-class life in Köln, Gottfried was interested in politics and became a socialist. This seems to have been the source of some tension: “Gottfried was the only family member who was politically active and he accused his family of a bourgeois lifestyle and carelessness.” He was a member of the SPD, the Social Democratic Party, until 1931, when he joined the more activist and radical splinter SAPD, the Socialist Workers Party, which wanted to take a more militant stance against the Harzburg Front, the alliance of the Nazis with the other nationalist right-wing parties.

While working for the SAPD, Gottfried met Helene Sälzer, the daughter of a union metal worker who raised his children to be die-hard social democrats. Although the Nazis hadn’t fully seized power when they joined the party, socialist groups were under constant harassment by the SS and SA and activism was dangerous. After a late night, clandestine meeting of a group of young SAPD cadre, Helene, who told her parents she was staying with friends, found herself with nowhere to go. “Then someone said to her: ’Give me your hand, you'll go with me.’ It was Gottfried Ballin who put up Helene at his house were he lived with his mother Anna and his brothers Wolfgang and Arnold. He gave her his room. In the morning Helene looked around the room and was fascinated by the many books.”

After the Nazi seizure of power, the SAPD attempted an underground campaign against the regime. Gottfried and Helene were both recruited by Erich Sander, the son of the famous photographer August Sander, to join a secret cell. Gottfried was put in charge of selling the party newspaper and collecting contributions. In 1933, the Ballins’ home was vandalized by Nazis, who painted the facade with antisemitic slogans. The house was also raided by the SS, searching for political writing. “They ripped everything out, drawers, cupboards, even prying open the floorboards. Finally they found a small box with Martin's war medals. So they saluted and left.” Anna soon thereafter was forced to give up the house due to “Aryanization,” selling it for a fraction of the value and moving to a small apartment. In the summer 1934, the cell was compromised and all members except for the two women, Helene and Clare, were arrested. It’s still not known who betrayed the group. Gottfried, ill at the time with what was suspected to be paratyphoid fever, was arrested in his hospital bed.

Gottfried was sentenced to five years in prison. He would never be released: he was instead deported to a series of concentration camps and finally to Auschwitz, where he was apparently killed after an escape attempt. His mother Anna did not want to leave the country or go into hiding while he was still imprisoned. She was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto, where she died in 1942.

In the process of researching Gottfried’s life, I discovered a couple of Holocaust researchers in Köln had collected his letters from prison and concentration camp, mostly addressed to his mother. I started to translate these letters for this newsletter, but then I abandoned that project. I will probably pick it up again in the future. The contents were difficult. So was researching more about Gottfried’s fate. One document I found in an archive online mentioned “Unfruchtbarmachung”—this means “sterilization.” This discovery made me physically ill. It was even more difficult to face than his murder.

I had been at sort of a low point in my life when I decided to apply for citizenship restoration and learning about Gottfried was very meaningful for me. He had interests almost exactly like my own: literature, social democratic politics, and antifascism. His letters are witty and sardonic, despite being imprisoned under terrible circumstances. I even thought he looked a little like me with his glasses. I felt encouraged to continue with my own projects for the sake of my family’s memory.

I am not sure why my grandfather didn’t mention Gottfried. It could’ve been that it was too painful to talk about. It could’ve also been that, as my father said, “maybe he just didn’t like him.” This seems very possible. My grandfather could be quite judgmental and particularly did not care for people he found to be self-righteous. It appears that Gottfried’s politics put him in tension with the rest of the family, which was upper-middle class and quite secure before the Nazi era. Here is an except from my grandfather’s memoirs, dictated to my sister, about being a young person during the Nazi period:

In 1934, my grandfather and his family fled to Palestine, then under British mandate. When the war broke out, he was visiting relatives in France and joined the French Foreign Legion, but more of that story another tine.

It’s difficult to fully express how I feel after receiving the citizenship restoration. On the one hand, I feel happy and satisfied. I feel that I am being finally given something owed. But I also feel strange accepting citizenship from Germany, this country that rejected and harmed my family. During the process, I felt sometimes a lot of resentment that they were taking so long and being so officious about it. Certainly they did not drag their feet kicking us out, so why the delay letting us back in? I feel ambivalent about attending the naturalization ceremony. I don’t think I would ever live in Germany for any extended period of time. (My grandfather also never wanted to return.) But I do feel happy that I am now a citizen of the European Union. And not just for the practical reasons of being able to live and work anywhere in the EU. My family came from all around the continent, so it feels right to rejoin that community: to be (at least partly) a European again. More than any particular nation on that continent, I feel attached to the cosmopolitan project of the EU. This may sound surprising: in an era of populism and nationalism, the EU in particular and cosmopolitanism in general have come into ill repute. But there is nothing to be ashamed of in this aspiration. The idea of a United States of Europe long been a goal of the continent’s progressive minds, from Mazzini to Victor Hugo to Marx. I have never been a Zionist, never been much attracted to Israel, and never been on birthright. For me, Europe is my “birthright.”

I also feel gratified to be part of the reversal and rejection of this Nazi law. A lot of people today hold antifascist politics in low regard: they believe it is retrograde, irrelevant to the present, or just plain embarrassing. All sorts of anti-anti-fascisms abound, some of them putatively well-intentioned, others in obvious bad faith. Some even think antifascism is just some kind of ideological mirage and involves the uncritical acceptance of liberal capitalism as the ultimate political horizon. Suffice it to say, I strongly disagree: For me, it’s a vital tradition that has both enormous personal significance and contemporary relevance. Part of what I’m doing in this newsletter and in my writing in general is an attempt to apply that tradition to the politics of today.

But sometimes I do wonder why I can’t just leave that Old World, with all its terrors and catastrophes, behind and dive into fully being a part of this New World, America? I guess that as a historian, one can never totally live in any new world. The old world is always still with us. For me, it is worth trying to understand how. The headline of one of the SAPD newspapers my cousin Gottfried helped distribute reads: “DIE TOTEN MAHNEN” — It can be translated as “the dead remind,” “the dead warn,” or, as I prefer to think of it, “the dead admonish.” The dead admonish us to continue what they began.

Thank you for this. One of my favorite things about your writing is your willingness to explain publicly how your personal life and history inform your political beliefs. Too many writers are coy about it, or perhaps aren't clear or honest enough thinkers to write about it in such a straightforward manner.

Thanks for sharing this, man. Like everyone else, I also found it really moving. It resonated with me because I recently went through kind of a similar experience. On a trip with my dad recently, he explained to me that my grandmother's extended family was exterminated when the Nazis took Rostov-on-Don in 1942. My grandmother, who was a medical administrator for the Soviet railroad, whose husband was killed in the Nazi advance on Ukraine, and who was in Moscow when the Nazis were advancing on it and helped coordinate medical care for people coming to and from the front, was able to save her mother after the Nazis had to give up Rostov-on-Don, and have her moved to Kazakhstan. Everyone else ended up "in the ditch," as my father put it. When I got home, I found an article in an journal of Holocaust studies about what had happened there, but I found it kind of hard to connect, the numbers were just too overwhelming; though learning that this was before the camps, in the "machine guns and gas vans" phase of things was very queasy. My grandmother, who I knew as a really kind and gentle and overall very happy person considering all that she'd lived through, never really talked about any of this stuff, and I had this weird feeling that, because she'd been lifted out of shtetl life by the Soviet Union, our whole branch of the family had been "pulled into the groove of history" (a phrase from Ellison's Invisible Man I think about a lot) where as these people had been, well, tossed into its ditch, and that there was no bridging the gulf.

Some time ago, when I was travelling to Germany a lot more for academic stuff, I was kind of toying with the idea of applying for Latvian citzenship, so I could work and travel freely. I was born in Riga, and my family left as Jewish refugees to America. This was kind of a non-starter from the beginning, since I would have had to pass a test in Latvian, which I don't speak and is incredibly hard to learn, but my father was vehemently against it, since he felt like Latvian nationalism dovetailed in a really big way with any anti-Semitism, with everyone dismissing tales of concentration camps as "Soviet propganda." (Of course, this is the history Putin is exploiting now.) The whole experience, that sense of not really belonging anywhere, or being from a place that no longer existed, really kind of impacted the way I think about American identity politics, which tends to sentimentalize the oppressed in a way that doesn't really work, to say the least, in the Soviet sphere. But it did make me feel, like you expressed here, that the project of European integration, is a worthy one.

Anyway, congratulations, and thanks for sharing all this. Just wanted to add my voice to express how much it moved me.