The Power of the Charlatans; Maurizio Serra on Malaparte; Bidenomics; Zoë Hu on Andrew Tate

Reading, Watching 01.19.25

Good morning! This is a regular feature for paid subscribers wherein I write a little bit about what I’ve been reading and/or watching. Hope you enjoy!

Today I have for you:

Returning to Grete de Francesco’s lost classic The Power of the Charlatan

Maurizio Serra’s newly translated biography of Curzio Malaparte

Where Bidenomics went wrong

Zoe Hü on Andrew Tate for Dissent

Seven years ago, very early in my career as a writer, I wrote an op-ed for the New York Times about charlatans, using a long out-of-print book called The Power of the Charlatan by a writer named Grete de Francesco. The primary target in the piece was Jordan Peterson and all the other snake-oil salesmen who seemed to be getting a level of public respectability at the time. In the piece, I labeled our era “The Age of the Charlatan,” which sounds a little bombastic—I was a younger man—but perhaps holds up okay. For example, if you read the recent interview with Curtis Yarvin in the New York Times Magazine, where he does his usual mixture of pretentious gibberish and utter commonplace, you might agree that the category of “charlatan” remains relevant. Not to mention all the other “influencers,” quacks, and prognosticators that seem to pop up by the dozens every day.

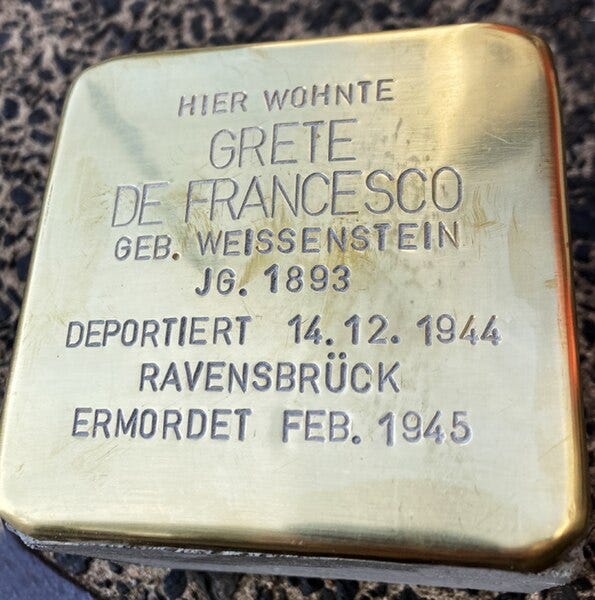

When I wrote the piece, I did not know much about de Francesco—there was not much easily accessible biographical information. I knew she was an Austrian journalist who wrote for newspapers like Frankfürter Zeitung and corresponded with luminaries like Thomas Mann and Walter Benjamin and that was about it. I should have guessed why she had no writing from the post-war years. Grete de Francesco was born Margarethe Weissenstein to a Jewish family in Vienna. She was the first woman to graduate from Berlin’s Deutsche Hochschule für Politik, with a thesis on the rise of Italian fascism. The Power of the Charlatan became recognized as the standard work on the subject of charlatans, but it was also a thinly veiled critique of the power of fascist demagoguery, published in Switzerland in 1937 in German and meant for cross-border consumption. In 1939, it was translated to English by Miriam Beard for the Yale University Press and the cover of the American edition bears the endorsement of Thomas Mann. De Francesco, who was married to an Italian man, seems to have moved around during the war years between Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, and in 1944 was arrested by the SS at her Milan apartment. She was deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp and murdered in February 1945, just a few months before the end of the war.

I hope some publisher—perhaps the New York Review of Books—will reissue The Power of the Charlatan soon. It’s beautifully written and contains real analysis and insights. As de Francesco, show the charlatan does not only sell fake elixirs but is also a propagandist, a master manipulator of public opinion. The charlatan thrives in periods of “rapid development of the sciences, or quickened progress in technology” when “minds are overburdened with the effort to keep up with these accumulations of facts.” In response to the confusing present, the charlatan provides simple nostrums for the public. They succeed under conditions of modernization and half-enlightenment: