Revisiting “Totalitarianism”

Reading Hannah Arendt After the Trump Years

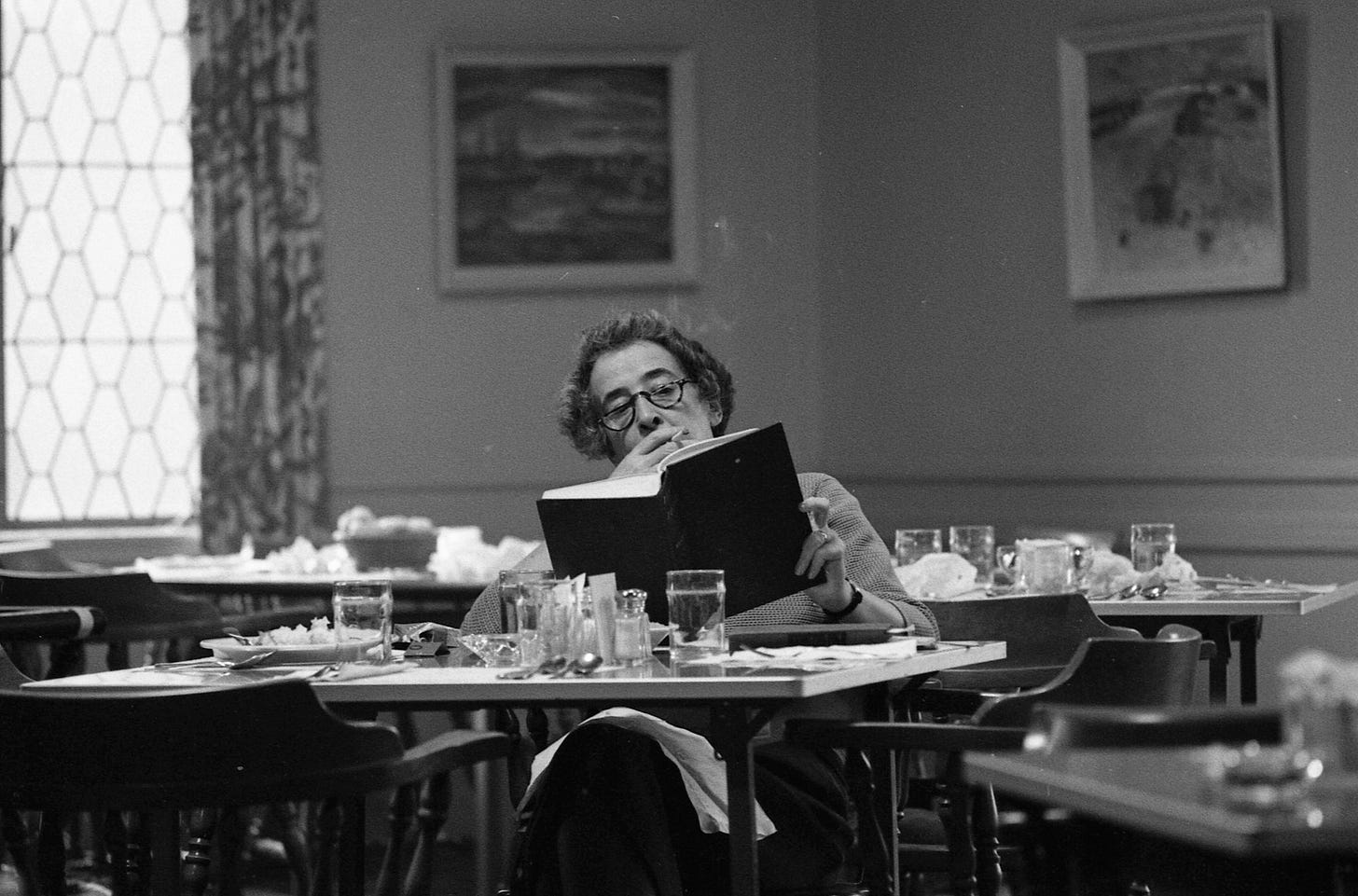

In the run-up to and immediate aftermath of Trump’s election in 2016, there was a small explosion of interest in Hannah Arendt among liberals, particularly in her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism. This was reflected in magazine and newspaper articles and you might even say memes: screen-shotted quotes from Origins that made their rounds on social media. Arendt, much to the consternation of some intellectuals, suddenly became middle-brow. Origins even sold out on Amazon. There was also something of a critical backlash to this on the left, with a number of articles questioning both the superficial uses of Arendt as an intellectual icon and the relevance of her thought to interpreting the Trumpzeit. In Harpers, Rebecca Panovka has a good essay in that genre, re-examining the Trump-era enthusiasm for Arendt, now with the benefit of some hindsight. Although it makes some strong observations and carefully attends to Arendt’s actual thought, I have a number of issues with it.

As far as I understand it, Panovka’s argument goes something like this: First, Trump’s extensive lies and the post-truth era supposedly ushered in he were not really “totalitarian” at all, they lacked, well, the totality of totalitarianism. His lies were merely ad hoc expedients for his own personal benefit rather than exercises in creating an entire alternate, Potemkin reality according to some ideological image. She writes, “Trump’s lies were less grand theory than self-aggrandizement—corporate bluster intended to artificially boost his own stock. He tended to inflate the numbers: how much money he was worth, how many people had attended his inauguration, how many votes he had received...His lies never progressed beyond the singular goal of saving face.” In any case, we were in no totalitarian danger because we had an aggressive, oppositional press that prevented his lies from becoming the dominant narrative.

Second, the cottage industry of Arendt-quoters did not do justice to the entirety of her oeuvre when it came to lying and “defactualization,” partly because of their tendency to view Trump as an aberration rather than a continuity in American politics. Panovka Arendt frankly states that lying has always been part of political life, but also that her works point out that ideological or fictionalized manipulation of the facts by government is not limited to totalitarian situations, but also occurs in liberal democracies. Panovka discusses the analysis of the government’s “image-making” revealed by the Pentagon Papers in Arendt’s essay “Lying in Politics” and applies a similar analysis to the George W. Bush administration, pointing to the lies that lead to the Iraq War and the damage this did to both the public credibility of government and the press. Trump was simply an opportunist, taking advantage of an already wounded public trust. “Trump did not need to create a make-believe world, because he appealed to those who had already lost confidence in the official representations of American political reality,” she writes.

This is all so far mostly persuasive, but here my objections begin. Panovka writes:

Trump’s loudest critics spent his time in office wringing their hands over “alternative facts,” worshipping fact-checkers, and fetishizing factual truth—declaiming Trump as an exception and yearning for a return to normal. But amid the criticism, they did little to examine the status of truth under previous administrations. Trump was not the first liar in the Oval Office, and unlike some of his predecessors, he was fiercely challenged by an adversarial press and an opposition party keen to decry his every statement. Rather than a calculating liar with an all-embracing plan, Trump was an opportunist able to exploit a lack of public trust in the institutions charged with disseminating facts. The journalists who nitpicked his statements managed only to preach to the proverbial choir, while his most ardent supporters shrugged off authoritative facts altogether, convinced that the media was aligned with the “deep state.” The press, after all, had already proved itself unequipped to dismantle the fictional reality constructed by the architects of American empire.

But elsewhere Panovka credits this “unequipped” press with preventing Trump’s lies from expanding their reach: “What was distinct, perhaps, was the way reporters responded to Trump’s lies. Throughout the Trump Administration, the press maintained an antagonistic pose, aggressively fact-checking the president. His narrative never had the chance to become monolithic, because an alternative story was always available.” This is a bind that critics of anti-Trump liberalism find themselves in often: they end up characterizing the liberal opposition to Trump as completely inadequate—”nitpicking,” “hand-wringing,” but also totally effective and sufficient and up-to-the task. So, which is it? Where they just preaching to the choir or were they aggressively preventing Trumpian lies from taking hold as the dominant narrative? And if this aggressiveness on the part of the libs was inspired in part by a kind of lazy inspirational-quoting of Arendt, among others, what’s the harm really? The problem is that viewing Trump “as an exception” lets the earlier dysfunctions of the American empire off the hook—I will return to that later.

Although Panovka does not seem to think the proposition that Trump is “pro-totalitarian” is worth taking seriously, her descriptions of his lying and absurdities, as well as the impotence and implausibility of the liberal opposition sounds strikingly like Arendt’s description of the “pretotalitarian atmosphere,” where the old “serious” pieties of liberalism no longer rang true for people. Panovka: “ The press, after all, had already proved itself unequipped to dismantle the fictional reality constructed by the architects of American empire” and “Trump did not need to create a make-believe world, because he appealed to those who had already lost confidence in the official representations of American political reality.” Arendt: “What the spokesmen of humanism and liberalism usually overlook, in their bitter disappointment and their unfamiliarity with the more general experiences of the time, is that an atmosphere in which all traditional values and propositions had evaporated (after the nineteenth-century ideologies had refuted each other and exhausted their vital appeal) in a sense made it easier to accept patently absurd propositions than the old truths which had become pious banalities, precisely because nobody could be expected to take the absurdities seriously.”

Another point Panovka comes very close to echoing Arendt is her description of Trump supporters’ reactions to his lies: “For the most part, his supporters were undeterred when his lies were unveiled, because they understood he was saying whatever was advantageous, not speaking as an absolute authority.” Here’s Arendt, in one of her most meme-d moments:

The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.

I think Panovka also glosses too quickly over the things in Trum’s orbit that smack a little more closely of totalitarian propaganda, with its “lying world of consistency,” like QAnon. Panovka writes, “Though he retweeted QAnon-linked accounts, he did not explicitly endorse the conspiracy. He invented facts as he needed them, flooding the field with misinformation.” That may be true, he may not have had the imagination or will to use things to the fullest, but the fact that he was a kind of magnet for totalitarian fantasies like QAnon is worth observing. It’s also worth pointing out he’s also has pretty consistently insisted on the alternate reality of the “stolen election” myth, which has a mass constituency.

On a recent episode of Know Your Enemy podcast, the hosts discuss a podcast featuring pro-Trump ideologues Michael Anton and Curtis Yarvin, where they fantasize about Trump doing Jan 6 right, invoking a state of emergency and suspending the law to stay. From the very beginning of his appearance on the political scene in 2015, Trump excited fascists and neo-Nazis, who were in no small part attracted to his racism, a major part of Arendt’s analysis in Origins curiously passed over entirely by Panovka. If he’s just a petty fraud, why is he so attractive to conspiracy theorists and actual fascists with grandiose dreams? I think it’s partly because Trump’s most insane ideological followers and his most dowdy liberal critics are in a way being better phenomenologists than some intellectuals: they recognize Trump’s kinship to their kind of politics even if he’s a very imperfect vessel.

While it’s true that Trump was not very good at shaping reality to his ends and exercising actual power, the things contemplated under his watch should be alarming. This facts are being forgotten or wiped out in the post-Trump reconsideration of his regime as only a kind of farce. Arendt writes, “One is almost tempted to measure the degree of totalitarian infection by the extent to which the concerned governments use their sovereign right of denationalization.” We should not forget that Trump’s was the first administration since the McCarthy-era to make moves at systematic denaturalization. Anton, then just recently out of his White House tenure as a national security official wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post about proposing mass denaturalization of birth-right citizens by executive fiat: “It falls, then, to Trump. An executive order could specify to federal agencies that the children of noncitizens are not citizens.” Trump even publicly announced he was taking this seriously.

When considering things like this as well the things that happened before, a deeper reading of Origins might be instructive. As Panovka points out, most of the book is dedicated to the precursors of totalitarianism—the first two sections are “Antisemitism” and “Imperialism.” The theme of the work is the collapse of European society in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the twentieth century. At the same time, during this collapse there’s a concomitant coming-together, a coalescing of the “subterranean” forces that would ultimately be identified as totalitarianism in a process Arendt calls “crystallization.”

The book…does not really deal with the “origins” of totalitarianism—as its title unfortunately claims—but gives a historical account of the elements which crystallized into totalitarianism; this account is followed by an analysis of the elemental structure of totalitarian movements and domination itself.

In a footnote to “Understanding and Politics,” she clarifies further:

The elements of totalitarianism comprise its origins, if by origins we do not understand "causes." Elements by themselves never cause anything. They become origins of events if and when they suddenly crystallize into fixed and definite forms.

As Panovka points out, since human freedom is at the center of Arendt’s thought, she’s at pains to avoid historical inevitability—things can always go otherwise:

An event belongs to the past, marks an end, insofar as elements with their origins in the past are gathered together in its sudden crystallization; but an event belongs to the future, marks a beginning, insofar as this crystallization itself can never be deduced from its own elements, but is caused invariably by some factor which lies in the realm of human freedom.

In other words, the elements are there but agency is required to put them into order—we are never on an inextricable road totalitarianism. But the “elements” that can suddenly crystallize into totalitarianism under the right conditions may nevertheless be present.

I think this metaphor of crystallization provides a key for reading Origins as it points to two of its sources: the tradition of European philosophy, specifically German Idealism and phenomenology, and the realist novel. The term “crystallization” appears in Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment, where he describes it as a “precipitation,” a “sudden solidification”, a kind of “leap” into order and form. This is given as an example of contingency and a counter-example to the belief in the inevitable, teleological unfolding of purpose and order in nature itself. The metaphor also points to Arendt training under Husserl and Heidegger in phenomenology, which tries to find identify and describe the structural underpinnings of experience.

“Crystallization” also appears in Stendahl’s On Love, the novelist’s essay on falling in love, where crystallization describes the process by which our the object of our desire takes on idealized qualities in our imagination. On Love, which Stendahl called a “book of ideology,” provides an analytical dissection of the illusions of love affairs and finds their roots in lower motives like vanity or lust, which are then given grandiose appearances in our minds. Stendahl inaugurates a literary tradition of disillusion, carried on by Balzac, Flaubert, and Proust, with its revelation of the hypocrisies of the bourgeoisie, the proximity of respectability to the underworld of vice and criminality, and the general shoddiness and decay hiding behind the glittering world of high society, as well as the general climate of cynicism that this engendered. Arendt refers repeatedly to Balzac and Proust, as well as other literary figures like Ibsen and Strindberg, throughout the text.

The focus on the pettiness of totalitarianism and forebears as well as their being at their root pathologies and by-products of bourgeois civilization is a theme Arendt develops throughout Origins, where she dwells on business failures and quasi-gangsters of the demimonde, figures that often sound distinctly like Trump and his especially his hangers on. She would bring this analysis of bourgeois pathology to its culmination in Eichmann in Jerusalem and her famous thesis of the “banality of evil.” This is why I think Panovka’s contention that Trump’s lies were mere public relations exercises— “boardroom bullshit”—actually makes Origins, particularly its earlier sections, more rather than less, relevant. Arendt writes in the section on Imperialism:

This privateness and primary concern with money-making had developed a set of behavior patterns which are expressed in all those proverbs—“nothing succeeds like success,” “might is right,” “right is expediency,” etc.—that necessarily spring from the experience of a society of competitors.

When, in the era of imperialism, businessmen became politicians and were acclaimed as statesmen, while statesmen were taken seriously only if they talked the language of successful businessmen and “thought in continents,” these private practices and devices were gradually transformed into rules and principles for the. conduct of public affairs. The significant fact about this process of revaluation, which began at the end of the last century and is still in effect, is that it began with the application of bourgeois convictions to foreign affairs and only slowly was extended to domestic politics. Therefore, the nations concerned were hardly aware that the recklessness that had prevailed in private life, and against which the public body always had to defend itself and its individual citizens, was about to be elevated to the one publicly honored political principle.

Or here, where her description of the bourgeois’s implicit totalitarianism sounds very much like a Trumpian philosophy of governance:

The bourgeois class, having made its way through social pressure and, frequently, through an economic blackmail of political institutions, always believed that the public and visible organs of power were directed by their own secret, nonpublic interests and influence. In this sense, the bourgeoisie’s political philosophy was always “totalitarian”; it always assumed an identity of politics, economics and society, in which political institutions served only as the façade for private interests.

Ultimately, I agree that Trump is not really like Hitler. As Panovka admits, most people using Origins even in clumsy or capsule ways did not claim that Trump was a totalitarian phenomenon, but rather was redolent, suggestive, proto-, or pre-totalitarian. I think that on the terms of Arendt’s own analysis, this is a really a fair conclusion to come to. Even Panovka seems to situate the current moment in Arendtian terms when she concludes: “In her view, the United States was closer to repeating the sins of British imperialism, but this ‘unhappy relevance,’ she warned, should not be taken to imply that history would inevitably repeat itself.” But again, imperialism is one of the “elements” that Arendt thought “crystallized” into totalitarianism.

History will not look like the past, but as Arendt writes, “it is the same world-and not some landscape on the moon-where the elements which eventually crystallized, and have never ceased to crystallize, into totalitarianism are to be found.”

Very interesting. But I wonder if you're still not downplaying the totalitarian threat. Before Jan 6th it was tempting to see Trump as an incompetent clown wrestling with forces largely beyond his control. But imagine the Chiefs of Staff had gone along with Jan 6th and installed him as rightful President, what then? I'm no expert on Nazi history, but isn't it true that when Hitler came to power in 1933 the German General Staff were still skeptical of him, and that it was only after the Night of Long Knives in 1934, where Hitler back the army over his paramilitaries and Rohm, that the General Staff came on board and swore an oath of allegiance not to the state but to the Fuhrer? Had Trump only been a bit smarter in winning over the Chiefs of Staff, surely we would have reached a roughly analogous position to Germany in 1934?

This is an excellent, thoughtful analysis, and your care and attention to both Arendt’s thought and the current situation are both much appreciated. I sometimes think Arendt’s comparatively straightforward language leads people to overlook the nuances of her thinking, but that’s very much not the case here. Great stuff.