Sam Tanenhaus's Buckley; Marcel Ophuls; More on MacIntyre; DOGE's price in blood

Reading, Watching 06.01.25

This is a regular feature for paid subscribers wherein I write a little bit about what I’ve been reading and/or watching.

If you are not yet a paid subscriber but regularly read, enjoy, or share Unpopular Front, please consider signing up. This newsletter is completely reader-supported and represents my primary source of income. At 5 dollars a month, it’s less than most things at Starbucks. And it’s still less than the “recession special” at Gray’s Papaya — $7.50 for two hot dogs and a drink.

Rabbit, Rabbit.

I know my newsletter is usually very serious (and probably quite depressing), but, for a little change, publicist extraordinaire—and, it is too often overlooked, wonderful writer—Kaitlin Phillips got me to write about my favorite sweaters for her terrifically successful Gift Guide newsletter.

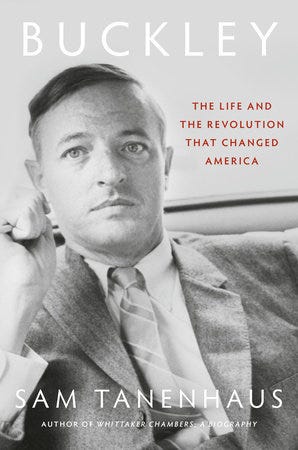

I’ve blurbed Sam Tanenhaus’s truly magnificent Buckley bio, out this week from Random House:

"Many of us have been waiting years for Tanenhaus's Buckley and it's well worth the wait. Tanenhaus's sparkling prose makes an already compelling subject irresistible. Not only a psychologically astute and subtle biography of a seminal figure, Buckley is now the definitive intellectual history of the conservative movement. William F. Buckley forever changed America and Tanenhaus's Buckley will forever change how we understand America."

I mean it! The prose is like butter: it’s a big book that glides by smoothly and magically feels very concise. It’s everything a biography should be: measured, humane, judicious—and dishy.

Last week, German-French filmmaker Marcel Ophuls died. Ophuls directed what I believe is the greatest documentary ever made, The Sorrow and the Pity, his two-part 1969 chronicle of France under Vichy rule and Nazi occupation. Not many films can be said to be great works of historical inquiry and to have changed history itself, but one might argue that The Sorrow of the Pity, along with Robert Paxton’s groundbreaking Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940-1944, published in 1972, permanently altered France’s conception of itself. The official post-war myth had been that the French were a nation of resistants; Ophuls’ reconstruction makes it clear that collaboration, not resistance, was the norm. This only makes those who did resist seem all the more heroic.

Ophuls’ depiction of France under occupation was so controversial that it was effectively censored in that nation until 1981. On a purely aesthetic level, it's outstanding as well, avoiding histrionics, layering subtle and dry dramatic ironies using the juxtaposition of newsreels and interviews that gradually reveal the truth. People often complain that political art is overly didactic or moralizing, but the balance of form and content in The Sorrow of the Pity avoids these pitfalls without losing sight of the stakes. It is worth watching for the interviews with the fascinating characters who lived through the era, which range from ordinary people to great personages like Anthony Eden and Pierre Mendes-France. My favorites include the group of socialist peasant maquisards in the countryside and an aristocratic army officer who disdained the republic and still hoped for a return to monarchy, but whose patriotism led him into the resistance. It is also available to stream, in its entirety, for free online. It’s long, but you can break it up into parts.

If you are still interested in Alasdair MacIntyre, I recommend this book review in The Nation by George Scialabba that puts MacIntyre in fruitful dialogue with a cosmopolitan liberal counterpart in Richard Rorty and offers a compelling critique of MacIntyre’s teleology and a defense of liberalism:

The concept of telos, so central to MacIntyre’s philosophy, is fatally flawed. He insists that the end or purpose or goal of human life is objectively discoverable and is the same for every member of Homo sapiens. But our purposes are not a matter of fact; they are a matter of choice. We don’t discover our goals as a result of scientific or philosophical research; we work them out, with much imaginative and emotional effort. Human nature is compatible with any number of teloses.

There are other, better ways—our usual ways, actually—of reaching moral consensus than by metaphysical arguments about a telos. Two people arguing about whether something is good may offer factual reasons, in case one thinks the other is misinformed, or may suggest that the other’s reasoning is faulty. If that doesn’t produce agreement, they may canvass principles and values relevant to the dispute, and if they share one and can agree on how it applies to their disagreement, then they’ve reached agreement. In the most difficult cases, however, facts and logic will not suffice: The disputants will have to reveal to each other the whole scaffolding of beliefs, experiences, and hopes underlying their positions, each one trying to see the issue with new eyes—or, more precisely, with an enlarged moral imagination.

This is a better way to describe our moral life than as a search for “rational justification.” The supposedly interminable and irresolvable disagreements MacIntyre laments should instead be seen as conversations: long-lasting, society-wide discussions that sometimes (as with slavery) issue in violence, but at least as often issue in consensus and even moral progress. Our national conversations about Jim Crow and interracial marriage ended in the 1960s. Our conversation about the full humanity of women appeared to have ended in the 1980s and ’90s, though Republicans and evangelicals seem bent on reopening it. Our conversation about homosexuality ended happily; our conversation about legalizing marijuana—maybe also psychedelic drugs—looks promising. Our conversation about economic inequality and reviving the New Deal is unfortunately going nowhere—but there was a New Deal, which is perhaps grounds for hope. Our conversation about global warming, alas, has barely begun. MacIntyre’s insistence that modern pluralism makes moral and political progress impossible appears to be at odds with history. Sometimes our supposedly regrettable pluralism actually produces desirable outcomes.

Contra MacIntyre, moral judgments incorporate both reason and emotion. Hume formulated that truth provocatively, saying that reason is always the servant of emotion. It’s what pragmatists like James and Dewey meant by identifying the imagination as our key moral faculty; and it’s why Rorty wrote that we should expect moral progress chiefly from the work of novelists, journalists, ethnographers, and other purveyors of thick descriptions rather than from philosophy.

Suffice it to say, progress looks a lot more fragile and these disputes much more intractable today. I also think MacIntyre’s concept of practices, each with its own internal goods, is compatible with pluralism. But of course, they must all hold together in some wider social and ultimate cosmic harmony, which may be asking a bit much.