Taking the Skinheads Bowling

Civil Society and its Discontents

In his recent New York Times column on the Canadian trucker protests, Thomas Edsall points to some interesting social science research about the connection between civic associations and the emergence far right politics that suggests there is a correlation between what’s called “social capital,” by sociologists and the Trump vote.

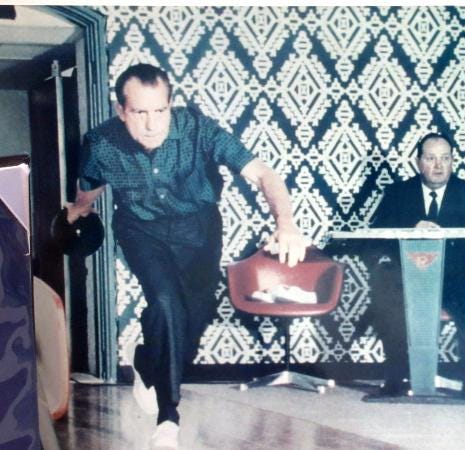

The old story of fascism and the origin of totalitarianism in general was that they were consequences of atomization: they preyed on the fragmentation and decay of social bonds and the transformation of society from an organized body of interests represented in clubs, voluntary associations, and political parties into a rootless mass of frightened, lonely, and confused individuals. The way to protect democracy in this understanding is to have a robust civil society that prevents the transformation of society’s classes into directionless masses apt to be seduced by demagogy and fantasies of power. This perspective borrows heavily from Alexis de Tocqueville’s understanding of the importance of voluntary associations. Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone is a famous example of this tradition: he took the decline in America’s civic life to be a hazard for its democracy.

But this picture has been questioned recently and researchers are now countenancing what’s been called the “dark side of social capital.” (After all, isn’t the Ku Klux Klan a form of civic association, too?) One of the papers Edsall refers to is entitled “Bowling for Fascism: Social Capital and the Rise of the Nazi Party” and argues that “dense networks of civic associations such as bowling clubs, choirs, and animal breeders went hand in hand with a more rapid rise of the Nazi Party.”

If you are familiar at all with Dylan Riley’s fascinating book The Civic Foundations of Fascism this will jump out to you. Riley’s argument in that book is that fascism is a “twisted and distorted form of democratization” that required—indeed, was a result of—societies with a highly-developed civil society but without a hegemonic political organization capable of national leadership:

Civil society development facilitated the emergence of fascism, rather than liberal democracy, in interwar Italy, Spain, and Romania because it preceded, rather than followed, the establishment of strong political organizations (hegemonic politics) among both dominant classes and nonelites. The development of voluntary associations in these countries tended to promote democracy, as it did elsewhere. But in the absence of adequate political institutions, this democratic demand assumed a paradoxically antiliberal and authoritarian form…Fascist movements and regimes grew out of this general crisis of politics, a crisis that itself was a product of civil society development.

Fascist movements offered to do away with the incessant back-and-forth of political immobilism and take care of things once and for all: they alone could fix it. According to Riley, the decline of civil society in the United States is one of the key things that makes Trumpism not fascist: “While fascism was a product of intense civil society and associational development, Trumpism is an expression of the etiolation and weakening of civil society. That is why Trump is more similar to Bonaparte, particularly Bonaparte II, than to the interwar fascists.” But, as another paper Edsall points out, Trump did especially well in places with remaining civil society networks:

The rise in votes for Trump was the result of long-term economic and population decline in areas with strong social capital. This hypothesis is confirmed by the econometric analysis conducted for U.S. counties. Long-term declines in employment and population — rather than in earnings, salaries, or wages — in places with relatively strong social capital propelled Donald Trump to the presidency and almost secured his re-election.

This immediately brought to mind Gabriel Winant’s n+1 essay “We Live in A Society,” where he argued, against Riley, that strong associational bonds still exist in the U.S. in the form of homeowners’ associations and the like and these often have an important racial component—what the authors of the above paper might call “the ‘forces of tradition’” that work to “restrict social change”:

How is the Trump phenomenon based in this kind of racialized civic life? First, it enjoyed a clear social-movement predecessor in the Tea Party, a genuine form of mass political association, based in the petit bourgeoisie, and giving prominence to figures like Sarah Palin, Michele Bachmann, Kris Kobach, Ken Cuccinelli, Steve King, Mark Meadows, Mick Mulvaney, Tom Price, and Mike Pence—all lesser versions of Trump, many of whom eventually joined the administration…Occasionally this movement intersected with paramilitary formations like the Minutemen or developed them as its own excrescences, as with the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters—prefiguring the various armed groupuscules of our moment. The substance of Tea Party ideology—a simultaneous commitment to the validity of white middle-class access to social protection and a belief that racial outsiders and young people were being unfairly favored by the welfare state—was only barely altered in the rhetoric of Trump’s 2016 campaign, which broadened the social base of the earlier movement, in particular incorporating more white members of the working class.

As I argued previously, if Reaganism represented a period of conservative hegemony, Trumpism should be understood as the Right’s politics during a crisis of hegemony, where there is an absence of “national-popular” leadership that can bond together different social groups under a broadly convincing story of the country’s purpose and direction.