The Cracker Barrel Hype(rreality)

Simulation and Simulacrum in America

I know I said I was going on vacation, but I’m waiting for my laundry, and I don’t leave until this afternoon, and I had a thought that I wanted to share.

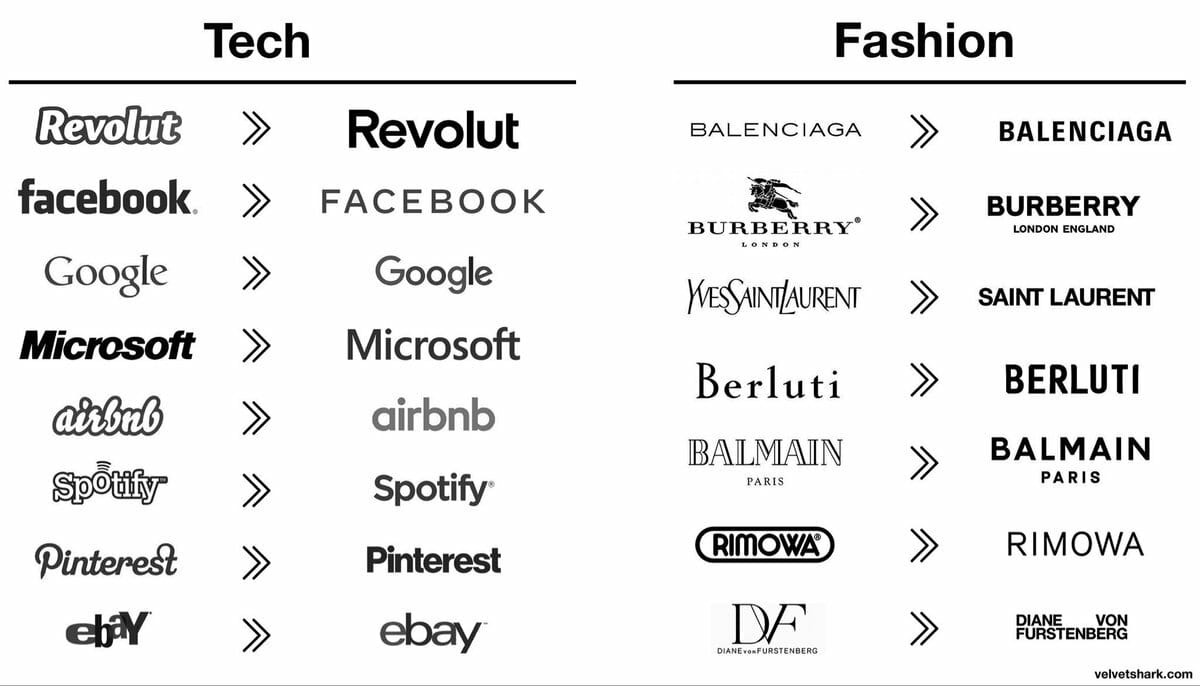

If you’re not online all the time like I am, you may not know that there is a national uproar about the changing of Cracker Barrel’s logo from its old-timey original to something more sleek and corporate. On the left is the old branding, and on the right is the new branding:

This an example of the simplification of corporate logos that has taken hold across the business world, what blogger “Lindyman” Paul Skallas calls “refinement culture.” (I think that’s a misnomer: it’s not refinement, it’s more like filtration.)

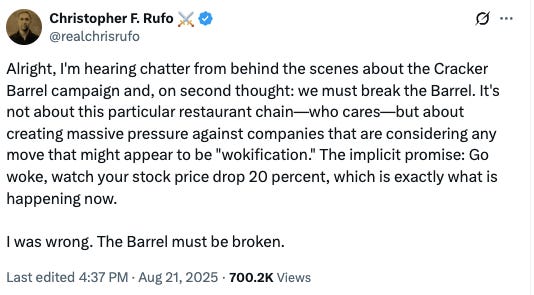

For a brand whose whole thing is nostalgia, I think it’s a pretty stupid idea to touch anything. But touch it they did: now, the stock has fallen, and a whole culture war fracas has started up. People suspect that the “liberal elites” are responsible for the destruction of their beloved brand. (Or, even, as it’s implied or sometimes said openly, the Jews.) The removal of the kindly old white man has raised racial anxieties about the “replacement” of “heritage Americans.” (They don’t call it cracker barrel for nothing, right? Sorry, I haven’t been able to make this bit work yet, but seriously, Cracker Barrel once had to settle a federal Civil Rights lawsuit under the George W. Bush administration for discriminating against minority customers.) Essentially, Cracker Barrel is thought to have gone woke. “We take no pleasure in reporting that Cracker Barrel has fallen,” one conservative organization tweeted, as if it were a city being sacked by barbarians. One of the right’s chief demagogues, Christopher Rufo, who never misses a trick, even jumped in on the action:

And for good measure, here’s a tweet from conservative Hillsdale College that I think captures the entire thing:

Now, most well-adjusted adults would probably look at this and say, “This is all totally ridiculous,” but the United States is not made up of well-adjusted adults; it’s made up of Americans. It may seem patently absurd, but I think this entire “controversy” tells us a lot about the mentality of the American right and the state of the national culture.

Cracker Barrel, of course, is not a real old country store or restaurant; It’s a replica of an old country store, an institution which had already gone the way of the dodo by the time the chain was founded in 1969. Conceivably, people could be nostalgic for the old stores in the early days of Cracker Barrel, but by now, people are nostalgic for the nostalgia, for the experience of going to a Cracker Barrel itself. As the Bulwark blog writes, it’s “a Xerox of a Xerox.”

There’s a fancy theoretical term for this: “simulacrum.” I’m, of course, referring to the work of the late Jean Baudrillard and his 1981 book Simulacra and Simulation. You may recognize it from The Matrix, where the cover briefly appears to make the movie look smarter than it is, despite having very little to do with what happens.

Basically, a simulacrum is a representation that no longer has an actual referent; there’s no preexisting reality it refers to, it has become the reality itself. Cracker Barrel is not pointing to a remembered Americana; it directly generates the feeling of Americana through its simulation of old-timey-ness. “When the real is no longer what it was, nostalgia assumes its full meaning,” as Baudrillard gnomically comments. It’s really the perfect example because Cracker Barrel wasn’t some old institution that got updated; it was always already a corporate simulation of country life. It’s a gimmick to sell gas, thought up by a Shell executive: It was meant to be plugged into the commercial matrix of the interstate highway system. People at Cracker Barrel are consuming the idea of communal wholesomeness and a pre-suburbanized society; the managers should’ve known this, but they fucked up. It’s the habit of high-tech morons to intone “we live in a simulation,” and, yeah, we do, but it’s happening at the Cracker Barrel, not because robot overlords are running the show. They messed with the matrix, and now the people are upset.

I hate to say it, but this whole controversy is a perfect example of Anton Jäger’s concept of “hyperpolitics,” which itself borrows from Baudrillard. Hyperpolitics reflects a political field dominated by social media and its swarms, trends, fads, and hysterias. As he writes, “it’s a grin without a cat: a politics with only weak policy influence or institutional ties.” It’s all about the battle over signifiers and semiotics, i.e., culture wars. The entire thing is about ginning up a thing. It’s also a simulation of politics, of public debate and deliberation about how we want to live.

It’s sort of pathetic to reflect that we have so few—maybe no—authentic and unmediated experiences that the thing that now really upsets people is an alteration of a simulation of authenticity. It’s felt as a loss of national identity on par with the defacement George Washington, because our national identity is now just corporate brands and consumerism. It’s no different than the “trad wife” fantasy, which is also a simulation and simulacrum of pre-modern living. You see this across the reactionary right, and it would be amusing if it didn’t muster real political energy: people genuinely angry over the loss of comforting consumer experiences. The attack on simulations is experienced as a trauma: remember the fury of gamers who felt their imaginary worlds were being tampered with. Not for nothing does Baudrillard refer to the “panic-stricken production” of simulacra and simulations.

It’s tempting to look down on people for this, but on further thought, it reflects a deep spiritual poverty in our country. The right is capitalizing on this spiritual poverty, both politically and literally, and saying, “Yes, theyyyyyyyy are taking yourrrr beloved things.” This forecloses anybody asking whether we might deserve more. An actual small town in America might have problems with drugs, unemployment, it might be reduced essentially to a ruin, but as long as Cracker Barrel or the equivalent exists, people can feel okay about the country. The question is never raised, “Hey, why are we being fed commoditized slop all the time?” It becomes, “I want the red-brand slop, bring me my red-brand slop!”

There is a mass experience of what Arendt called “worldlessness,” the absence of a common world and common experiences, which leads to the loss of a common sense that could put the lid on absurd hysterias like this one. If you point out the poverty and say, “Hey, this is not healthy,” the right-wing populist move is to attack you for being a liberal elitist, which is kind of true. You are, because you don’t have an alternative except snobbery. Conservatism is now the protection and hoarding of old-seeming simulacra and simulations, hence all the AI-generated “traditionalism.”

Naturally, this brings me to fascism. On the one hand, fascism might seem to be an awkward fit because there was still some volkisch referent, a memory of pastoral existence, in the fascist imaginary. But that, too, was already a kitschy simulacrum of the pre-modern past. And while the proponents of the “hyperpolitical” are doubters of the fascism thesis, Baudrillard himself thought that hyperpolitics would generate fascism in its desire for signs of real power and from its troubled relationship to the half-remembered past:

Power itself has for a long time produced nothing but the signs of its resemblance. And at the same time, another figure of power comes into play: that of a collective demand for signs of power-a holy union that is reconstructed around its disappearance. The whole world adheres to it more or less in terror of the collapse of the political. And in the end the game of power becomes nothing but the critical obsession with power-obsession with its death, obsession with its survival, which increases as it disappears. When it has totally disappeared, we will logically be under the total hallucination of power-a haunting memory that is already in evidence everywhere, expressing at once the compulsion to get rid of it (no one wants it anymore, everyone unloads it on everyone else) and the panicked nostalgia over its loss. The melancholy of societies without power: this has already stirred up fascism, that overdose of a strong referential in a society that cannot terminate its mourning.

There’s a lot in there. You can read conspiracy theorization itself as a nostalgia for the reality of political power in a situation where people feel powerless. “The melancholy of societies without power,” that is to say, societies that have no real way to express the democratic will. “A society that cannot terminate its mourning” is pretty dead-on about how we are all coping with the world-loss of the internet.

Now, if I were a thoroughgoing Baudillardian, I’d have to interrogate whether or not my antifascism itself is a kind of simulation and simulacrum of an older, more meaningful world. But I think I’ve gone down the rabbit hole enough for today.

“It’s a gimmick to sell gas, thought up by a Shell executive.”

What’s more authentically American than that?

Not sure if people are genuinely upset about the "loss of old-timeliness", or they just pattern match any current event to "might be interpreted as woke" and pile on. E.g. if Buc-ee's hat were to change the color from red, that would be a Huge National Scandal, an anti-MAGA conspiracy.