The Future that Never Was

Japan and the Lost 21st Century

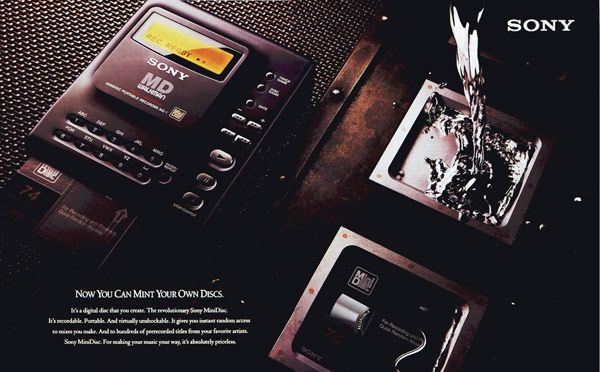

I find myself drawn to obsolete and discarded technology. There’s a Twitter account (and now Substack) called “Obsolete Sony” that I often scroll through. On eBay, I’ll routinely check the prices of Minidisc players, and one day I’m sure I’ll impulse buy an old piece of stereo equipment like an Akai reel-to-reel machine. On St. Mark’s Place in the East Village, there used to be a store that sold old video game consoles that I loved to browse. An embarrassing confession: When I was a teenager, I organized a “retrocomputing” panel at a hackers’ convention that was dedicated to discussing old and outdated personal computers. A second embarrassing confession: a lot of these old gadgets I like are Japanese.

Some of this is surely just nostalgia and a longing for lost youth. These objects reflect old desires: things I wanted as a kid but wasn’t allowed to have or couldn’t yet buy for myself. My childhood coincided with the era of Japanese dominance in consumer electronics: Nintendo, Sega, Sharp, Panasonic, and Sony were the big brands. Japan was cool, and it seemed to be producing not just futuristic things but the future itself. I miss that future.

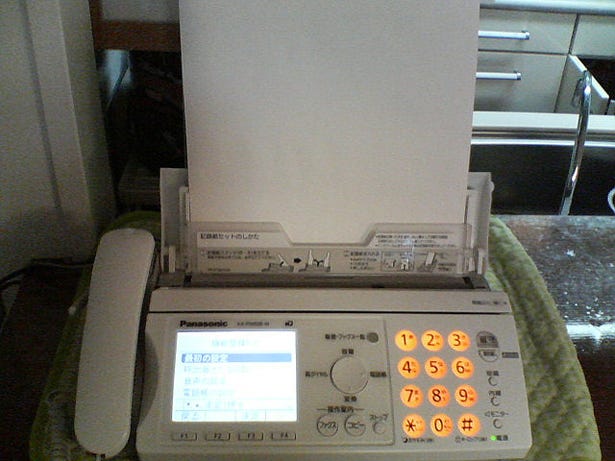

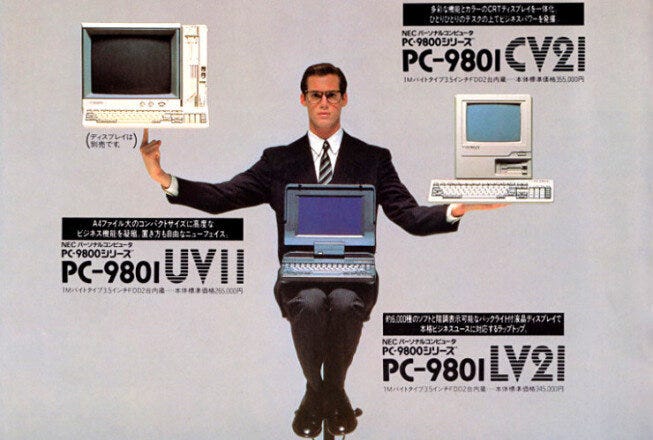

In fairness, I’m not the only one who doesn’t want to move past this era. Japan itself remains attached to its archaic tech: an article from CNN asked, “Japan used to be a tech giant. Why is it stuck with fax machines and ink stamps?” Just last year, the government finally declared victory in its long war on floppy disks. Although Japanese firms produce state-of-the-art video game consoles and handheld devices, arcades persist. Many observers comment on the peculiar hodgepodge of innovative devices and out-of-date media in Japan: the long persistence even of CDs, DVDs, VHS, and cassette tapes. Western workers at Japanese companies are bemused by text-only email systems and website design that looks like its from 1998. Partly this is hanging on to old tech is because of the sclerosis of Japan’s sprawling bureaucracies, but even the small and medium businesses that proliferate in Japan’s economy are also attached to old tech. Since I don’t have to do business in Japan, I find this very charming.

Some chalk this up to intrinsic Japanese conservatism, and some of it is certainly because Japan’s workforce is aging—like I am—and more comfortable with old things. There’s a debate to be had about whether the soft Luddism of Japan is more cause or consequence of its economic stagnation, but there are other, more touching suggestions about why Japan resists upgrades. Fax machines, in particular, are still liked because people can send examples of their handwriting, which conveys subtleties of meaning and personality not possible through type. There is also a kind of shared social resistance to automation to keep people employed. An article from the BBC posits, “…despite the tech-loving public image, much of corporate Japan seems intent on circling the wagons against automation and using people rather than machines whenever possible. After all, those faxes don't pick up themselves.” This “overstaffing” may hurt productivity and entrepreneurialism, but unemployment in Japan is currently just 2.5 percent. Perhaps the persistence of physical things makes a more human world possible.

I think that there’s something more going on here than a longing for lost childhood or the toys that little John wasn’t permitted to have. There’s also a nostalgia for the future, for a better future. Economists speak of the “Lost Decades,” so we might speak of the “Lost Future.” Japanese consumer electronics and Japanese engineering and product development in general represented a high point of 20th-century capitalist civilization and a possible next step, a glimpse of how industry doesn’t necessarily need to produce an endless stream of disposable junk, but can produce objects of lasting beauty and value. It can make things that people are loath to part with and even want to preserve and collect. We can see in them a possible balance between the prerogatives of quantity and quality, which feel so out of whack in contemporary life. We can use them, as some did in the recent past, to envision a less alienated form of labor that is neither a regressive return to outdated modes of production nor subjugation to ever more atomized and isolated forms of social relations. And perhaps, on the political level, there is even the possibility of an alternative to both the “abundance” model and the reactionary modernism that has seized Silicon Valley and society in general.

This might sound quite literally like “commodity fetishism,” and of a very dubious, orientalizing sort at that. But I hope it’s something more like Walter Benjamin attempted in his uncompleted masterpiece The Arcades Project: sorting through the refuse and detritus of history and finding in discarded things the what he called the “dialectical image,” where what was “lively” and still “productive” in a historical epoch would reveal itself along with what was “abortive, retrograde, and obsolescent.” (A…Video Arcades Project…if you will.) Benjamin connected this method—if you can really call it that—with childhood memory and dream interpretation. “Every childhood achieves something great and irreplaceable for humanity, by the curiosity it displays before any sort of invention or machinery, childhood binds the accomplishments of technology to the old world of symbol,” he wrote. I’ll try to rifle through the bargain bin, and read the rise and decline of Japanese production as an allegory of modernity, attempting an interpretation of the 80s and 90s dreams of futuristic Japan.

Dream and Nightmare: The Phantasmagoria of Japanese Commodities

That the future would be Japanese was once a given: It was to be a dreamlike metropolis, a phantasmagoric city full of Japanese logos and brands in neon signage, shops, and glass towers. If Paris was the capital of the 19th century, and New York of the 20th, surely Tokyo would be the capital of the 21st. This dreamscape was sublime and dystopian: the cyberpunk megacities of Blade Runner and William Gibson's novels. Obscure megacorporations in glass towers would rule the world. A borglike collective entity seemed to hum behind the facades of the office towers; something leaderless, cruel, and hyperefficient. Streets teemed with indifferent masses, scurrying from drudgery to hollow entertainments. Of course, this fantasia was tinged with racial anxiety: Fredric Jameson called it “a semiotic combination of First World science and technology with a properly Third World population explosion.” This signified the fear of Japan that took shape in the Japan-bashing discourse of the ’80s and ’90s and the whole Japan panic literature of that era—what I’ll call “Japanic” lit from here on out.

But America’s Japan fascination also had a Utopian side. American observers were astonished at the cleanliness and convenience of Japanese cities, with their spotless streets and bullet trains. The Japanese factory floor in particular was idealized as a site of teamwork, innovation, and consistent quality. The Japanese worker was praised for his commitment and self-sacrifice to a larger whole. While in the Soviet Union, collectivism seemed to bring only creativity-killing conformity, in Japan, the collective spirit was portrayed as organic rather than forced. Americans were thought of as becoming soft and idle consumers, but the Japanese remained productive. In the 1930s, Japanese engineers visited Ford and GM factories to learn American techniques; 50 years later, the roles were reversed: U.S. automakers were looking for ways to copy Toyota.

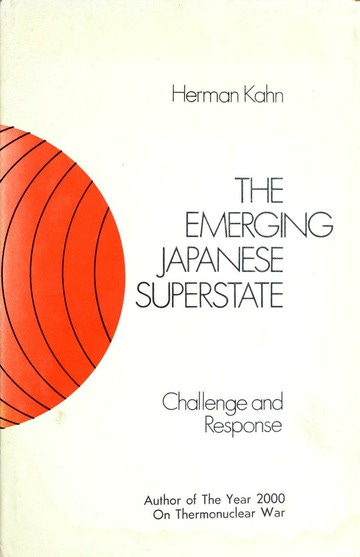

How did the Japanese do it? This is what Americans wanted to know. From its very start, the American discourse on Japan found that there was something different about Japanese capitalism. Not for nothing did the proliferation of this writing coincide with a period of stagnation and deindustrialization in the United States, while Japan appeared to be undergoing miraculous growth and development. The first Japanic book, The Emerging Japanese Superstate, appeared in 1970 and was written by Herman Kahn, the RAND corporation strategist, author of the horrifyingly cheerful On Thermonuclear War, and inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. Kahn’s book laid out many of the conventions of the genre: a mix of actual policy analysis and armchair sociology that dipped into cultural essentialism. The underlying notion was a rebooted “Yellow Peril” mythology: We had to either defeat or emulate this foreign adversary, or we’d be left in the dust. The ideological function here is obvious. American deindustrialization and decline get a tidy narrative and a clear-cut enemy figure with racial characteristics — “They don’t even look like us.” (America was still then very white.) It didn’t hurt either that America still had a living memory of the Pacific War and Pearl Harbor to deepen the sense of distrust.

The Japanic literature did not begin in earnest until 1979, with sociologist Ezra Vogel’s Japan as Number One: Lessons for America. Vogel enjoined Americans to emulate the whole suite of Japanese institutions that made its miracle possible: a good education system, state encouragement of business, lifetime employment, and strong social cohesion. In 1982, Chalmers Johnson published MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, which ascribed Japan’s prowess to its powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry, which protected, incubated, and forced cooperation within Japanese industry. Japan was not a free market economy like the West, but was guided by a strong developmental state, and corporate and public bureaucracies worked in tandem, but, it avoided the pitfalls of socialism by allowing competition among the major firms, which could seek out the loyalty of consumers with high-quality products. To Johnson, there wasn’t something about this Japanese culture so much as this particular political-economic setup.

The 1980s and early 90s saw an explosion of books and articles that sought out the Japanese secret. These ranged from serious analysis to crackpot conspiracism and downright racism, and often combined bits of all. Predatory Japanese trade practices became a major complaint in America, contributing to a push for protectionism that took 40 years to come to fruition. (There’s an interpretation of Trumpism possible that frames it as a long tail of the Japanic lit: the Donald was famously apoplectic about Japanese economic power in the 1980s. )

What all these analyses, from the most scientific to the most ideological, seemed to imply was that Japan had somehow solved the basic collective action problems of capitalism. A chaotic, self-seeking consumer society was tempered by cultural (and it was often implied, racial) cohesion. Just-in-time and lean production techniques seemed to solve the problems of plant overcapacity and idle capital. The keiretsu system, the close cooperation of banks, government, and industry, insulated firms from market pressures and shareholder revolts, allowing them to pursue long-term strategic planning. Fratricidal competition between firms was replaced by a network of mutually interdependent suppliers. Class struggle had supposedly been overcome by lifetime employment: workers would be loyal to their employers and be paternalistically taken care of in turn. Commoditization was apparently solved by “monozukuri,” the persistence of pre-capitalist Japanese artisanal traditions that incorporated care and beauty into Japanese products and worked to increase their handiness while still being able to produce them en masse. The “kaizen” philosophy of continuous improvement seemed to allow for a process of innovation that did not require sudden, wasteful outlays of capital investment and was not socially disruptive but organic and gradual. The Japanese miracle was really that the fundamental contradictions of capital had been overcome: the island nation was situated perfectly between past and future, it was both pre- and post-capitalist, and it managed to combine high productivity, high quality, stable employment, and sustained profits all at once. Of course, after the bubble burst and Japan entered its stagnation period, it was quickly discovered that many of the same institutional dynamics that led to the miracle had created a “crony capitalism” that was responsible for the downturn.

Suffice it to say, Japan did not have some special, ahistorical substance but rather a particular history of industrial development that differed from the West and allowed it a period of strong export-led growth. And it was not insulated from the West so much as integrated with it: as collaborator, competitor, and sometimes enemy. Technology transfers, trade, and mutual borrowings had much more to do with the story than opposing cultural essences. Not to mention Japan’s post-war economic restructuring was overseen by American New Dealers. But those things are complicated and hard to explain fully. It’s much easier (and more ideologically functional) to say “they’re just different.”

Beyond Fordism to Fujitsuism

There’s an artifact of the era of Japan discourse I find particularly compelling in the way it saw Utopian potential in Japanese production methods while avoiding gross cultural overgeneralizations. It came from a group of scholars working in the “regulationist” or “social structures of accumulation” school. What that approach contends is that each era of capitalism possesses a “mode of regulation,” a system of interlocking social norms, institutions, technology, and labor relations that creates the conditions of possibility for a “regime of accumulation,” a stable pattern of how production, consumption, and investment generate profits. In the 20th century, the system that worked for a time was Fordism, which combined mass production, mass consumption, relatively high wages to support said consumption, with intensive division of labor into specialized, routine tasks. But by the late century, the Fordist settlement appeared to be breaking down and leading to increasing social deterioration and conflict. What would replace it? For researchers Martin Kenney and Richard Florida, in a 1988 paper entitled “Japan’s role in a post-Fordist Age” and a 1993 book, Beyond Mass Production: The Japanese System and its Transfer to the U.S., Japan provided a model for the future.

Kenney and Florida wave away suggestions that Japanese profits were maintained through hyper-exploitation of workers without a strong labor movement, although they admit the existence of the infamous karoshi phenomenon, or death by overwork, and an extreme gendered division of labor in the workforce. Instead, they proposed that Japan had pioneered a real advance in capitalist labor relations. They called this replacement to Fordism “fujitsuism” after the computer company Fujitsu Limited. Where Fordism broke down the production process into deskilled assembly line jobs with the help of heavy machinery, Fujitsuism reintegrated intellectual and manual labor in a kind of high-tech craft production. Unlike the rusting hulks of the Midwest, the Fujitsuist shop floor was a combined laboratory, school, factory, and artisan’s shop:

The new shop floor…integrates formerly distinct types of work—for example, R&D and factory production, thus making the production process ever more social. In doing so, the organizational forms of the new shop floor mobilize and harness the collective intelligence of workers as a source of continuous improvement in products and processes, of increased productivity, and of value creation.

There is a clear ecological dimension, too, a vision of productivity and innovation without pollution and waste: “The factory is no longer a place of dirty floors and smoking machines, but rather an environment of ongoing experimentation and continuous innovation.”

Kenney and Florida hang on to their hardcore Marxian bona fides by placing the emergence of the Fujtuist model within the history of class conflict in the Japanese factory, and they assure their readers, “Far from being romantic or naive, this view recognizes quite explicitly that the new industrial revolution exploits the worker more completely and totally than before.” But there’s a clear excitement and deep curiosity about what they saw happening in Japan. There’s a reason why the epigraph of the book sets Marx’s words alongside those of the chief of Sony.—

If you know your Marx at all, you can see what they are getting excited about: from his earliest works Marx was concerned with the process of alienation that took place under capitalism: the alienation of the worker from the product of his labor, his alienation from the labor process as a mere machine operator, the alienation from his fellow workers, and alienation from the creative and skill-enhancing process of human labor as part of a system of mass production. Fujitsuism seemed to mitigate or relieve this complex of alienation without necessitating a reactionary movement backwards to an earlier mode of production; it remains highly modern, indeed, futuristic. Just as the Japanese consumer product seemed to overcome the commodity form by preserving use and beauty, Fujitsuism seemed to overcome the commoditization of labor.

Back to the Things Themselves

When people try to figure out what went wrong with the Japanese economy, they point out that Japanese firms stayed hyper-focused on the hardware innovation they once excelled at and lost out in the shift to software development. While American companies developed “A.I.” as computer processing models, Japanese firms kept working on embodied robots. The very physicality of the Japanese electronic renaissance is what adds to its lasting charm. Now, just a few devices handle so many tasks and so many things are online or in the “cloud,” that we don’t no longer need a wide variety of tools and objects. We just need one screen. The experience of working on the screen becomes increasingly dematerialized with A.I., to the point where we barely even have to craft thoughts. Without the anchoring presence of physical things, we don’t have a shared world. Perhaps this explains part of the Japanese resistance to the digital takeover. I quickly replaced my MiniDisc player with the iPod when it was available, but I never miss the iPod, yet still find myself yearning for the much less useful discs.

The true usefulness of the computer and the internet, and its replacement of many things that required dedicated devices, makes it doubtful we can return to a world of built things. Only hobbyists and collectors will seek to fill their lives with old objects, and can only ever be a subset of the general population. . But perhaps there remains a hint, a glimpse of a different future in this past: a world of interesting and well-made discrete objects to interact with and inhabit rather than an endless desert of scrolling content and a form of production that is neither dull drudgery and endless repetition nor disembodied brain work. Can we imagine what non-alienating technology might look like? Perhaps with the help of the golden age of “Made in Japan,” we can.

My favorite, not to mention only, interesting factoid about “rise of Japan” paranoia in the 70s and 80s was that in the original version the company in alien was called Weyland Corp. and they changed it to Weyland-Yutani to tap into subconscious fears about Japanese multinational buying everything up

The full resurrection of the vinyl record does show there is a mass appeal to use physical, less convenient objects with more soul, though.

PS : there is an optimism to the "past future" of that era that one finds a lot in Kraftwerk's very dated but still widely popular music, as well.