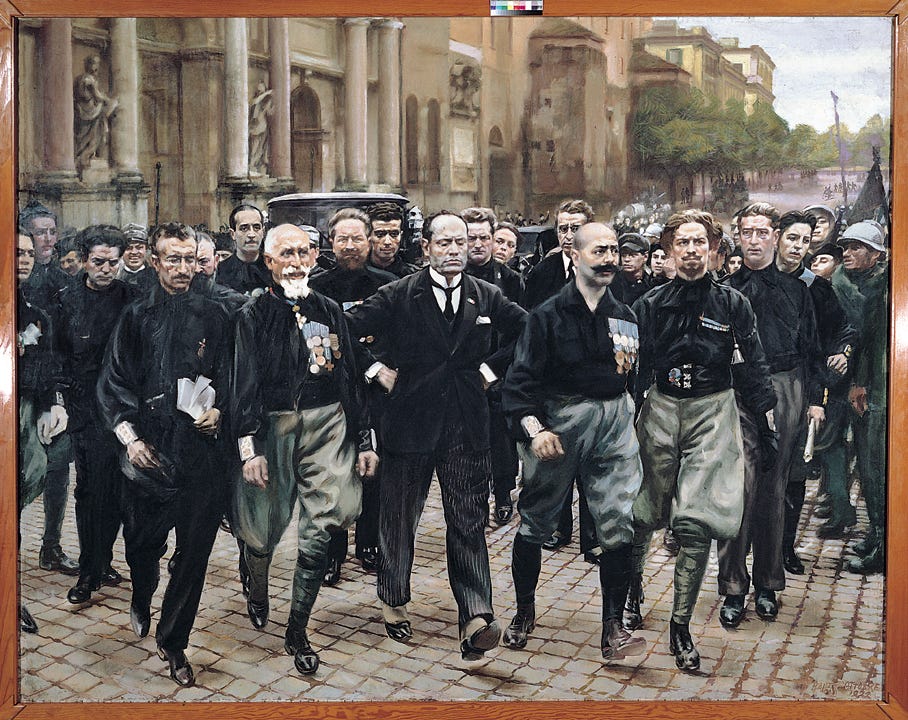

The March on Rome, One Century Later

A Response to Adam Tooze

If you are tired of the never ending “fascism debate, I don’t blame you and you may want to just skip today’s newsletter. But there are two recent pieces out that deal with the question that I believe are worth taking a look at. For the sake of brevity, I am going to deal with one today, and the other one, which I think much less of, tomorrow.

First, there is a reflection on the 100 year anniversary of the March on Rome on Adam Tooze’s Substack. The post, based on the recent book by Clara Mattei, The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism, is mostly a look at the role liberalism played in early fascism. Italian liberals were both political collaborators and also the architects of a state policy that favored austerity and “stability.” But abroad, liberal and conservative elites also had high hopes for fascism as a constructive force in world affairs. This was “technocratic-fascism,” one of the “hyphenated fascisms” that historian Alexander de Grand writes about. Here I think is the key point:

Mussolini’s regime, in other words, was not per se an alien force, an “other” that was rejected from the existing international order. On the contrary it was understood, especially, in the 1920s as a force of order, offering a new set of solutions to the problem of capitalist governance and one which forward-thinking liberals and conservatives associated themselves.

The Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises was expressing a whole climate of opinion when he wrote in 1927, “It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.” As Tooze points out, many leftists know this history intimately already and always grasped that capitalists were willing collaborators with the rise of fascism. But it’s worth noting that at the time fascism was a genuinely new, progressive phenomenon and it attracted a lot of curiosity and interest from all over the political spectrum. The avant-garde of fascism in Italy included many former men of the left, of which Mussolini is only the most prominent example. In a way, it’s possible to understand how seductive fascism might have looked at the time: it offered a “history-making” role and it made a number of competing—if not utterly contradictory—claims and promises, which offered to solve problems that neither socialism or liberal democracy had been able to meet. Those who saw from the very beginning in fascism the utter disaster and crime that it actually represented were often either faithful devotees of older traditions or people of unusually perspicacious judgment. Today, we don’t have the same excuses.

Unsurprisingly, Tooze offers the Keynesian tradition as an alternative to the classical liberalism that countenanced fascism as a possible solution to the interwar crisis. Although I shade a bit to the social-democratic left of Keynesian liberalism, I am sympathetic to this. On the whole, the post is very interesting and I admire Tooze a great deal as a historian, but I have to dissent a bit from some of the things he writes there.

Tooze believes that the analogy between fascism and present-day right wing movements is misguided because the conditions are entirely different:

….if we aim for is a general historical understanding of fascism, I would argue that we have to see it as shaped by three framing conditions. (1) the experience of total war; (2) the active threat of class war and revolution; (3) the shadow of the end of history as defined by the rise of Anglo-American global hegemony.

All three contexts shaped both Mussolini and Hitler’s movements. We can relate to all three of these dimensions form the point of view of 2022, but in large part through difference and contrast rather than similarity of situation.

Mussolini and Hitler were both combat veterans whose politics were defined around that experience. The fact that we mercifully have no experience of total war, helps to make the 21st century in Europe and the US distinctly post-fascist.

Both Hitler and Mussolini railed against the new American-led world order that emerged after 1918. Hitler did so at greatest length in his speeches of the late 1920s, collected in the compilation we call his “Second Book”. Mussolini, who was more of an intellectual, and more aware of the world scene launched his critique of Wilsonianism already in 1919. He defined Italy’s position as that of a proletarian nation that must struggle against British and American plutocracy.

I think it’s undoubtedly true that classical fascism took on its particular shape from these contexts and it does not emerge in the particularly strong and virulent form it did without them. Both culturally and materially, the First World War and its concomitant revolutions gave classical fascism its formal qualities: both the cult of the combatant and the mass organization of party and paramilitary squad were forged in this crucible. Bourgeois sympathy and support for fascism certainly had much to do with the live threat of proletarian revolution represented by the Soviet Union and the upheavals in Europe after the First World War. But it’s worth pausing here to ask how live was it? By 1922, the Socialist in Italy party was fractured and was no longer a threat to the state. The idea that the March on Rome “saved” Italy from revolution, like much of what’s been handed down to us, was a piece of fascist myth-making. As Tooze points out, “Hitler came to power in a “situation quite unlike the postwar inflation and class conflict that provided the backdrop to Mussolini’s seizure of power” and the KPD was not in a position to launch a revolution. The situation there was no longer that of pitched class struggle, but of demoralized masses, unsure of where to turn. In France, the events of February 6 1934, when far-right leagues attacked parliament, were triggered by a domestic political scandal involving corruption. The notion of a possible Communist coup at that time was a figment of the fevered right-wing imagination and its propaganda efforts. The government that the French far right feared was secretly “Communist” was solidly center-left. Ironically, it was the putative threat of French fascism that pushed France leftwards and the Radicals into coalition with the Socialists and the Communists. Still, I am willing to grant Tooze’s point: revolution and class struggle, even when they were more fears than realities, contributed a great deal to the dire atmosphere of the time.

I’m also willing to grant that Tooze’s “post-fascism” (semi-fascism, perhaps?) may be a better descriptor for these attenuated movements than just saying they are identical to classical fascist movement when they are clearly not, with a few caveats. First, it’s interesting to me that Tooze talks about Fratelli d’Italia as his prime example of “post-fascism.” It’s true that while Meloni’s party is in clear historical lineage of Italian fascism, it lacks street fighting cadre or any kind of serious rhetoric about undoing liberal democracy and replacing it with a wholly other kind of regime. I imagine Meloni’s government will probably fall in short order like other Italian governments.

But the anniversary of the March on Rome seems like it would be a good occasion to talk about January 6th, which was, although a failure and some might say a farce, a similar move on power that combined attempted parliamentary maneuvering and features of a coup d’etat. Trump lacks the tightly-organized squads of Mussolini and Hitler, which can probably be attributed to the absence of interwar features that Tooze describes, but the fact remains there are paramilitary groups that have put themselves at the service of Trump. While we lack the experience of the Front, these groups, which are rich in military veterans, take inspiration from the tactical special forces squads of the War on Terror, rather than the storm troopers of trench warfare. (It’s interesting to recall here briefly that one of earliest precursors to fascist squads, the Marquis de Morés street thugs during the Dreyfus Affair, dressed up like cowboys.) Are these paramilitaries as big a feature in American politics as either the Brownshirts or the Blackshirts were in interwar Europe? No, but again I believe we are talking about an attenuated and weaker version of a similar phenomenon. But Trump’s rise was certainly conditioned by anxieties about the waning of American hegemony in the face of China. The paradox of the present situation may be that the movements in the U.S. are a bit more fascist than those in Europe.

A quick sidebar: If we are going to talk of a post-fascist era, we should also talk of a pre- or proto-fascist era. Before World War I, an era of peace in Western Europe and the movement of most socialist parties to reformism and parliamentary compromise, saw the emergence of a political culture that anticipated fascism in many ways. In France alone, you had General Boulanger’s farcical failed coup that united the anti-democratic left and right, the street mobilizations and psychotic propaganda offensives of anti-Dreyfusards, and Action Française’s combination of paramilitary cadres and anti-democratic propaganda apparatus. In Italy, you had D’Annunzio’s nationalism and his “operatic dictatorship” in Fiume, to borrow Talmon’s wonderful phrase. In Germany, there was the Volkish movement, with its anti-liberal and anti-semitic “politics of cultural despair,” to quote Fritz Stern. All over Europe there was a cultural revolt against liberal democracy as corrupt, ineffective, and spiritually deadening and visions of a new order that combined democratic mass politics with an autocratic or renewed elite leadership. To many observers of the era, like Antonio Gramsci, the emergence of fascism seemed less like a totally new thing and more of a continuation of this kind of “reactionary Caesarism” that began to crystallize before the First World War. Anton Jäger once described the contemporary far right as “Pétain without Verdun;” one might also say, “Anti-Dreyfusards without a Dreyfus.” Does post-fascism sometimes resemble pre-fascism? I believe that’s worth looking into.

To return to the present, let me, once again, summarize what I believe are the pertinent facts of the Trump years: A charismatic outsider to the political system offered himself as a providential solution to a national crisis brought on by failed wars and economic debacles, “the only one who could fix it,” offering a program of restored “national greatness” to salve a wounded and humiliated domestic pride; he directed rhetoric against both corrupt elites and racial minorities; he menaced and then ultimately coopted the existing conservative elite; who believed they could ride his movement to getting their policy agenda through; he offered a sort of technocratic government of the smartest” while being a populist alternative to the present elites; he provided a menu of contradictory and competing vague policy ideas that included nods to redistribution but ultimately catered to the needs of business; a cult of personality formed around him with messianic and millenarian fantasies; the extreme right and figures of the conspiratorial mob demimonde rallied to him as a long-hoped for messenger of their kind of politics; he employed reality-defying propaganda and the mass rally; right-wing intellectuals began to envision him as a kind of emergency, custodial dictator that could put the country back on track and save it from the radical left. As silly as it seems to anybody rooted in reality and while there is no imminent threat of left-wing revolution in the United States, the right regularly pushes the propaganda line that liberals and “the left”—as they call anyone not a conservative Republican—are actually hard-core Marxists bent on totalitarian domination and one or two steps away from accomplishing it. Sometimes this propaganda has a distinct antisemitic flavor.

It’s true that in office, Trump was unable to establish control, but we should also look at the first years of Mussolini’s premiership: he worked within the old constitutional order and only later with a crisis and the acquiesce of the political elite did he establish a dictatorship. And, ultimately, with the assistance of his paramilitary supporters and a mob, Trump tried to bluff his way into maintaining power and overthrowing an election and the constitutional order. It’s true that Trumpism is not the well-oiled fighting machine of a fascist party, it’s something much more loose, amorphous, and incompetent. Yes, it’s not conditioned and disciplined by the extreme conditions of interwar Europe, but it’s not a totally different beast. But as Tooze piece makes clear, fascism was much more a coalition than a monolithic juggernaut. It’s tempting to remark that it’s not surprising that the American iteration of fascism would be a bit corpulent and lazy.

But here’s I come to the same point I feel I have to make over and over again. However different the conditions are today, the fact remains that believers in the “fascism thesis,” as “fatuous,” to borrow Tooze’s word, as the position may sometimes appear to serious intellectuals, have had a better grasp of the arc of Trump’s movement than their critics. Even in its crudest version of the notion that there was something fascist about Trump anticipated something like January 6th, while many who rejected the idea out of hand told us that such a thing was inconceivable. How dangerous are these post-fascist movements? I’m not sure, but I think we can now say a bit more than their doubters thought, but also maybe a bit less than the most alarmist among us think. Are they likely, in the present form, to successfully overthrow established liberal democracies in the West? Again, not sure, but probably not. But if conditions became more extreme, like the interwar period, could these trends reconsolidate and crystallize into something more virulent? Yes, I really do think so, which is why I think it’s worth taking them seriously. As Tooze’s piece inadvertently points out, without the benefit of historical hindsight, today’s elites, like those in the 1920s and 1930s, may hear in these siren appeals “interesting” possible solutions to contemporary crises, rather than recognizing in them a very old tune.

somehow every doctrinaire ancap worshipper of Mises and company fail to mention that quote in between their exhortations about the NAP, soliloquys on gun ownership, and screeds about the uniquely horrible evil that is the income tax, funny that

Great post. Some questions surfaced for me that I would be interested to see you tackle at some point.

You said: "there are paramilitary groups that have put themselves at the service of Trump." My sense is that right-wing extremist (incl paramilitary) movements are growing, while Trump's place in those movements is declining. However, there is no obvious political successor to Trump in terms of what he represented to those movements. I wonder if this will persist as a patchwork of extremist groups for a while, and whether there are precedents suggesting how it might play out.

The US is so vast and diverse, and actual far right political views are widely unpopular, so I wonder if the consequences of a successful 'semi-fascist' takeover of the federal government (and probably some states) would be a failed state, almost immediately – as in, the US would effectively dissolve. This in contrast to the kinds of unifying nationalistic movements you focus on. CA, for example, is powerful in its own right, and distant from D.C.