The Ordinary Heroism of Alexei Navalny

What Now?

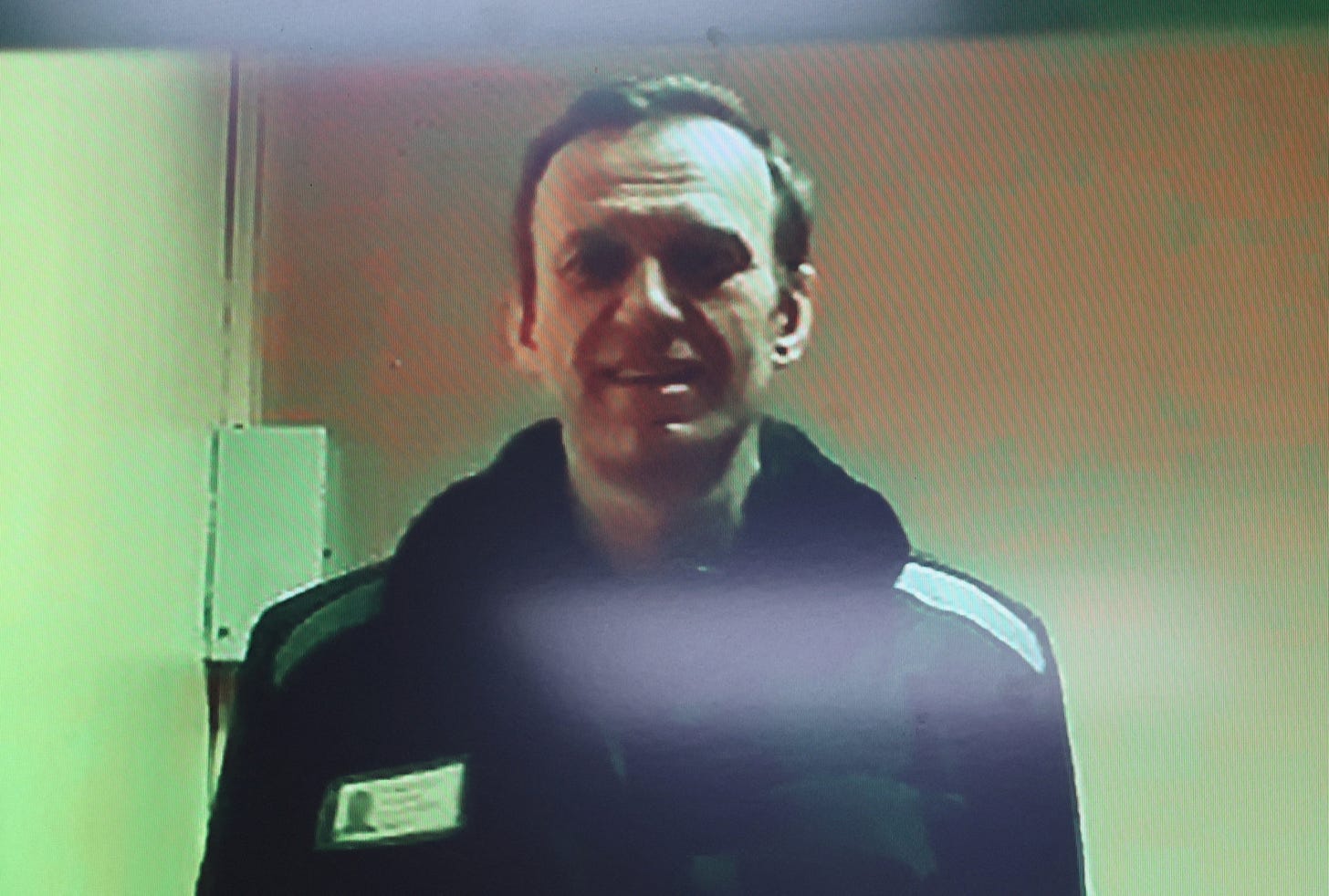

Did Putin kill Navalny? It seems ridiculous to even wonder, but let’s consider the available evidence. First, Putin already tried to kill Navalny in 2020 by having FSB operatives poison him with the nerve-agent Novichok. Second, the circumstances of his death are highly suspicious: he suddenly collapsed after a walk; the cause of death given was “sudden death syndrome.” A paramedic told the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta that there were bruises on Navalny’s body, which he said might have come from attempts to hold him down if he was convulsing or they might have “indirect cardiac massage,” attempts to do CPR, in other words. The day before his death, Navalny appeared relatively healthy: he was joking around in a video court appearance where he was given 15 days in solitary confinement for a dispute with a prison official. In December, Navalny was transferred to the “special regime” prison colony known as “Polar Wolf,” a remnant of the old Soviet Gulag system, where temperatures regularly hit negative 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Even if a direct order was not given for his death, this was part of a deliberate effort to torture and break him. His transfer seems to be related to the upcoming “elections” in Russia and part of a pattern of moving opposition figures to harsher conditions: in January, Vladimir Kara-Murza to a higher security prison. (A victim of attempted poisonings himself, there’s reason now to also fear for Kara-Murza’s life.)

But why kill Navalny now and risk turning him into a martyr? The insistence of Navalny and other opposition leaders is that this regime is not only brutal and corrupt, but also stupid. Navalny, with the help of independent researchers, was able to easily discover the FSB agents that attempted his assassination in 2020 and even prank call them, getting one to admit his part in the plot. Much of the regime’s moves appear tactical, improvisational, and ad hoc: reactions to evolving conditions they fear might get out of hand, rather than long term strategies. Putin dips into the toolkit of the secret policeman, the only thing he really trusts and knows: black propaganda, sabotage, and assassination are his favored methods of governance. But even granting the regime is not omniscient or omnipotent, one must not miss the underlying message, one they seem intent on sending to every serious opponent: “You will die alone.” They want to instill a sense of helplessness and terror. Civic life is solidarity and joining together for a common purpose; the regime wants to keep the population demobilized, in a state of apathy, alienation, and atomization. “Oh you want to stand up? Well, see what happens.” Navalny would not accept silence or exile, so he had to meet the fate the regime decrees is predestined for such people.

One should pay homage to the extraordinary courage—heroism–that Alexei Navalny showed, while at the same time reflecting that the need for heroes at all comes from a tragic and even desperate situation. After his poisoning, Navalny returned to Russia in full knowledge of the fate that awaited him: imprisonment and, very likely, another attempt on his life.

Navalny could have become an ordinary or even disappointing politician. Ukrainians in particular look suspiciously at the fact that he once marched alongside the nationalist right. Without excusing this, it also has to be contextualization as a mark of the impoverished political situation in Russia: nationalism, at one time at least, was one of the only alternative currents to the regime. Part of what transformed him from just another name into the de facto leader of the Russian opposition was his leaning into his very ordinariness. He drew political strength from his normal appearance against a regime that so often attempts to tar its opponents as strange or degenerate. While he was certainly handsome, he put on few pretensions or airs; he appeared to be a nice, loving good-humored, happily married dad. And so he offered Russians another image of how to be a man: neither gangster patriarch, nor raving nationalist fanatic, nor intelligence operative, nor impossibly intellectual dissident genius either. He presented himself as a concerned citizen first and as doing the duties of one. He talked about his positions in terms of common sense. In short, he acted as if he was the citizen of a democracy even if he did not live in one. In essence, he said, “I’m just a normal person who has the right and the responsibility to say and do these things.”

But what made him heroic was not the adoption any ideology or ideal, beyond very basic notions about democracy and human rights: it was his consistent act of refusal. He refused to take any of the avenues the regime offered him: exile, membership in the impotent, managed liberal opposition, or a lifetime of far right resentment. Above all, he refused to take the regime seriously. To the very end, he mocked it. His anti-corruption campaign labeled Putin’s United Russia party as “the party of crooks and thieves.” The message was not this is not a “state” as such, not the bearer of some great civilizational destiny, merely an organized crime enterprise.

Navalny’s death and his personal heroism, coming so quickly after Tucker Carlson’s audience with Putin, inevitably casts that even in even more shameful light: Carlson, from a position of total safety, furrowed his brow and took Putin seriously, called him “sincere,” and let him bloviate at length about Russia’s historic claims. He had a once in a lifetime opportunity that another journalist would kill for: to sit before an extremely powerful person and ask anything without fear. While positioning himself as a bold truth teller, Carlson is, in fact, a spoiled brat who reserves his sneer for the less powerful. He long ago gave up the vocation of journalist to be a propagandist. One thing I know for certain: no one will risk jail to offer flowers when Tucker Carlson one day dies.

Whatever criticisms one might have of Navalny, and even though he was the product of a dire situation that is quite different from ours, we can still profit from his example in the West: he was neither cynical nor credulous, two stances which so often come down to the same thing. He remained focused and directed his ire at the right people. He went down fighting. One hopes that political life in Russia will not long require heroes and martyrs, just more ordinary citizens.

A lot of Russians moved to Serbia after the invasion (one of the European countries with a remaining direct flight to Russia plus overall friendly relations between the two countries). Pro-Russia, pro-Putin sentiment is widespread in Serbia, and so it is a funny situation that the actual Russians that have come here, are generally very much not Putin fans. The day Navalny died, they held a little vigil downtown. Our government is not as bad as Russia's (yet) but it was still a personally risky thing to do given that some anti-Putin Russians here have had their Serbian visas cancelled for being a bit too outspoken.

John, surely this would just be speculation, but I wonder if you have any thoughts on the ideology or motivations of individuals like Max Blumenthal or Aaron Mate, who predictably are excusing, denying or minimizing Navalny’s death and the obvious crimes of Russia. Is there any historical parallel for someone nominally “left” coming around to far right fascists in this fashion?