The Other Side of the Canvas

The Historic Compromise with Fascist Art In Italy

On this trip to Rome, I’ve been struck by the apparent nonchalance of Italian society toward the cultural legacy of the fascist era. I shared a cab into the city from the airport with a professor of architecture, who was very pleased to point out the interesting buildings at the Foro Italico, the massive sports complex built in the 1920s and 1930s that was once known as “Foro Mussolini.” (Only on passing the Foro a second time did I notice the giant obelisk still reads “MUSSOLINI” in massive letters.) Italians I’ve met, particularly those involved the arts, tend to shrug when I ask about the moral questions involved in displaying art from the era. “Well, it’s beautiful,” they say. And to be perfectly honest, these encounters have been more amusing than scandalizing to me. The vibes are not particularly bad. The fascist-era buildings don’t convey the same haunted, post-apocalyptic feeling of Nazi constructions like Tempelhof Airfield in Berlin. One reason is surely just the lightness and airiness of mediterranean Rome itself that resists any dour, gothic spookiness of the North. Another is the antiquity of the city and its chaotic pastiche of different eras: seeing buildings from the 17th century right next to ruins from the 1st century C.E. makes any particular historical episode seem like a small detail, just another curiosity in the eternal museum. Fascist architecture may have tried to dominate its surroundings, but doing trying to do that in the Eternal City seems like a fool’s errand, which brings me to my next point.

It’s sometimes just difficult to take Italian fascism entirely seriously. Mussolini’s mugging now looks mostly preposterous, silly. (This was true even at the time: in Churchill’s speech to Congress after Pearl Harbor he referred to “the boastful Mussolini” and got a big laugh.”) Compared to the radical evil of Nazism, Italian fascism can even seem relatively harmless, a kind of farcical dress rehearsal for a darker performance. But this of course relies on forgetting momentarily the serious crimes of the regime: the wave repression and murder during its consolidation of power, the invasion and colonization of Ethiopia, the adoption of the Racial Laws in 1938, and its cooperation with Nazi Germany’s aggressive wars and the Holocaust. Not to mention just the encouragement and inspiration Mussolini’s seizure of power gave to his imitators and admirers throughout Europe, including Adolf Hitler. Still, I feel some license to see the dark humor in the stupidity of fascism.

I am not the only person to have noticed this apparent lack of urgent moral and political concern about the fascist past. Yesterday, I attended a lecture at the American Academy by two art historians, one Italian and one American, who edited a book about the exhibition of fascist art in Italy. The impetus for their project was a 2018 show at the Fondazione Prada, “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918-1943.” (The title is from one of the nonsensical sound poems of Marinetti, one of the founders of the Futurist movement, and was meant to ape the sounds of battle.) The exhibition was spectacular in all senses of the term and even recreating many of the spaces where the work was shown originally, but did not include much in the way of critical reflection about the political context.

This temptation is some way understandable. Benito Mussolini’s fascism was much more intellectually and artistically formidable at its roots than Nazism, with many adherents being avant-garde Futurists before being fascists. There was more freedom given to different styles of creative expression under the regime, and much of the work created under its auspices and patronage was actually interesting, compelling, and in some cases, even beautiful. From a purely aesthetic perspective, you can recreate impressive effects by just recreating the conditions of the time, but the question becomes do you then reproduce the seductive propaganda power of the work as well?

It’s a complicated question, but I have to confess that coming from the United States, where there’s so much handwringing over the moral content of museum exhibitions, it’s been sort of refreshing to see things without the hectoring commentary. But I am relatively informed about the fascist-era and don’t need to be told it’s bad. Plus it’s kind of more interesting for me to experience these things as a person back then might have. Even taking that all into account, it would not have been too hard to add some text and images that would remind people that this era was not all about grand exhibitions, but that these striking aesthetics were directly put in the service of oppression, war, and genocide.

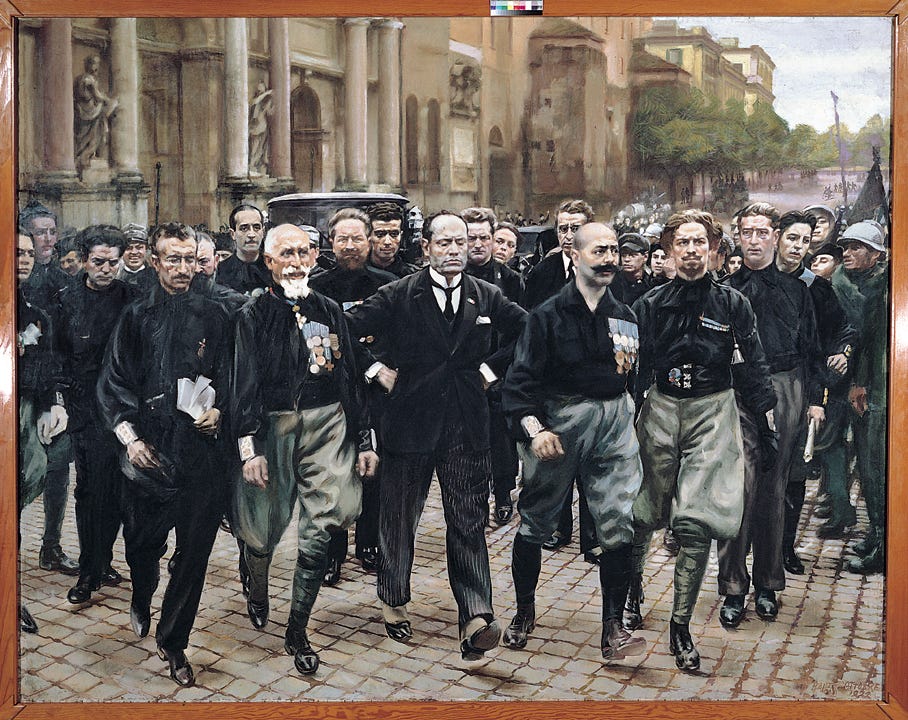

The most interesting painting, or two paintings rather, discussed were by Giacomo Balla, a leading member of the Futurist movement. The first, entitled Velocitá Astratta—”abstract velocity”—is from 1913, the pre-fascist era, and is a masterpiece of Futurism’s idealistic, slightly cracked, but now a bit charming attempts to represent abstract qualities like “speed,” “movement,” “force” themselves. It’s a good painting, but also a legitimate one: it’s recognizably modernist, conforming to a style and movement that’s been granted art historical significance for its purely formal accomplishments. But on the other side of the canvas, there is quite a different painting from the same artist: a realist, historical painting of Mussolini’s March on Rome, painted for the tenth anniversary of when the blackshirts occupied the city and secured Il Duce his place in power, signaling the end of parliamentary democracy in Italy.

It’s pure propaganda, not the least for being literally false: Mussolini was not even in Rome during the events of October 28th, he was with his lover Margarita Sarfatti, herself a critic, curator and patron of the arts, outside of the city, unsure of the outcome and ready to flee the country if necessary. This painting actually depicts Mussolini at the head of the parade after his position in government had been secured, but it gives the impression of the strongman leading his troops into battle.

Going from seeing one painting to the other was kind of a shock and I actually couldn’t suppress a laugh, because of how different it was aesthetically, the comical aspect of the tough guys in the painting, and just how kitschy and absurd it is overall. What a departure from the high modernism of the other canvas. It’s a little bit like an early iteration of the “How it Started, How it’s Going” meme. It seems almost too perfect an encapsulation of the cultural contradictions of fascism: on the one side, a kind of attractive, modernist movement, emphasizing a break with the past and progress, a fresh start, and on the other, totally retrograde in both its aesthetics and politics, pathetically toadying to the powerful, and just, well, idiotic, signifying the total absence of culture or ideas.

In 1939, the American art critic Clement Greenberg famously proposed an opposition between avant-garde and kitsch, with the former being the “advanced” art of abstraction, modernism, dada, surrealism etc. and the latter being associated with schlocky popular art, but also the official styles of Stalinism, fascism, and Nazism. But the presence of both avant-garde and kitsch on literally two sides the same canvas by the same artist suggest a problem with the easy dichotomy of his polemic. Perhaps there is less of an opposition than we would like to think: maybe avant-garde and kitsch live in a symbiotic relationship. Balla’s double-canvas reminds that fascism is always both: avant-garde and kitsch, and it’s difficult to fully divorce one side from the other. The avant-garde abstraction into attractive notions like “power” as such obscures just how ugly and stupid power really looks like in practice.

This painting, though, seems to finally have been direct and brutal enough about its fascism to finally kick in the Italians’ sense of shame. While it was exhibited briefly so one could see both sides, now at the private foundation where it’s displayed today, it’s been set into the wall so you can enjoy the impressive modernist side but can’t see the March on Rome side, in effect entombing that embarrassing fact. What better emblem of Italy’s attitude to the whole issue? “We can have the cool stuff, and let’s just kind of ignore the bad stuff.” There’s something very funny and disarming (and therefore characteristically Italian) in how bald-faced it is. But perhaps it’s also indicative of the political consensus and compromises of post-war Italy.

Unlike Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy removed its own dictator: Mussolini was captured and hung by partisans. This act created the appearance of internal purification and made an anti-fascist mythology the basis of the new Republic. All of the leaders of the principal parties, the Christian Democrats, the Socialists, and the Communists, had been opponents of the regime. There was never anything like Nuremberg, denazification, or the eventual internal reckoning about the Nazi years in Germany. The famous “Compremesso Storico” of the 1970s that resulted in the surprising coalition government of the center-right Christian Democrats and the Communist Party was made possible in part by the anti-fascist alignment of both parties and, in a sense, it was an alliance against extremism.

But there is the another side of the canvas: the Communist leader Enrico Berlinguer’s decision to pursue the strategy was based not so much on democratic idealism as the pragmatic fear of a right-wing military coup like the one that happened in Allende’s Chile, and the years of the historic compromise coincided with the Years of Lead, the period of extremist left-wing and right-wing terrorism, with all its whispers about neo-fascist agents provocateur with deep ties to the Christian Democratic establishment and the C.I.A. The left-wing belief in a secret fascist army backed by the NATO and United States has some basis in fact: in the early 1990s, former Christian Democratic leader Giulio Andreotti confirmed the existence of the shadowy Gladio organization. As is often the case, militant anti-communism allowed fascism to come in through the back door. And certainly, the total cynicism and irresponsibility of the Berlusconi era further eroded Italy’s defenses against fascism. More recently, the anti-fascist mythos of the post-war era has not blocked the return to electoral prominence of far-right parties like Fratelli d’Italia or Lega Nord.

The compromise formation of post-war anti-fascism in Italy, with its paperings over, toleration and intentional blindspots, has never been totally successful at preventing the return of the repressed. The reassuring ideas of the Popular Front-era in culture, like the simple separation of avant-garde from kitsch, elide much of the more ambiguous reality. Setting the canvas in the wall so nobody can see it, a guileless piece of guile, also doesn’t really work. The question is whether whatever replaces it can possibly be any better.

Great post John!

I was thinking about the 'forgotten' episode of occupation in Yugoslavia (with Italianization, work (maybe death?) camps for Serbs, and partisan massacres), so I googled around a bit and found things like a link to a Stormfront (!!!) post about it (I did not click the link), but I found this article in the Telegraph, of all places, from April 2021:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/04/11/italy-faces-calls-come-terms-dark-wartime-past-80-years-invasion/

The academics in the article seem to be on much the same wavelength as you, and it seems that the political establishment in Italy has very studiously ignored them.

elm

'if we want things to stay as they are, things will shhhhhhshutupshutupshutup...'

"a kind of farcical dress rehearsal for a darker performance"

This invocation of the "preposterous, silly" aspects of Mussolini, reminded me very much of Lina Wertmuller's films, especially Love and Anarchy. You have the head of the police, Giacinto Spatoletti, appear as this boastful buffoon, but in the end you see the violence that is behind all of the boasting.