The Shadow of the Mob

Trump's Gangster Gemeinschaft

So, Donald Trump is now a convicted felon. Will voters mind? Certainly not his core supporters: for them the charges were always, as Trump would say, “rigged.” But maybe even those who are not the MAGA faithful but view Trump in a more ambivalent way may not be much bothered by Trump’s official status as a criminal. And some might even find something attractive in it.

Yesterday, The New York Times published a forum with 11 undecided voters on Trump. Here’s a little part of it that I think is quite telling:

As my friend Eric Levitz quipped on Twitter, Resistance Libs like to say, “Trump is a sociopathic gangster.” Pro-Trump swing voters respond, “Yes, exactly!”

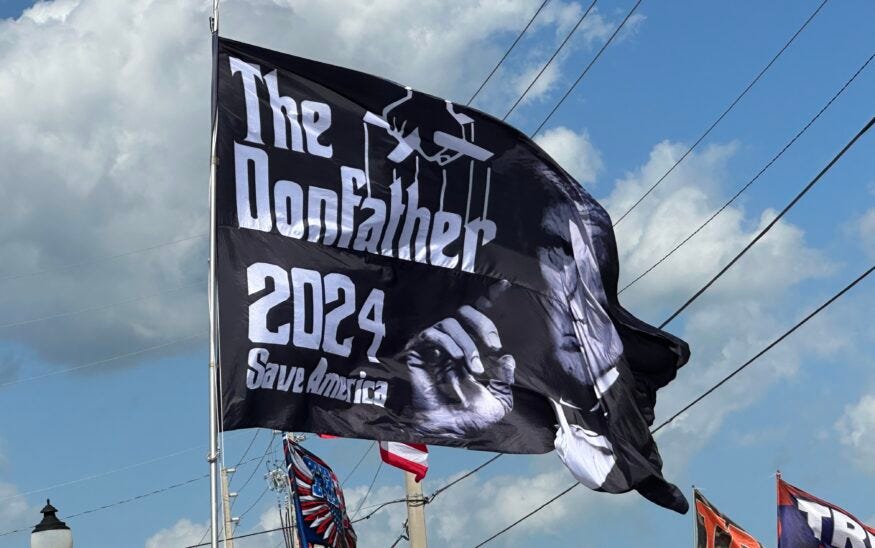

Trump talks and acts like a mafioso. He’s not trying to hide it. He has compared himself to Al Capone frequently. The New York Times reported last week, “Trump Leans Into an Outlaw Image as His Criminal Trial Concludes,” This is not all just theater, either. He really comes from the world of the mob. His lawyer and mentor Roy Cohn also served as house counsel to the Gambinos. The deal for the concrete for Trump Plaza was worked out with Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, boss of the Genovese family, in Cohn’s living room. The Trump family’s political patron in Brooklyn was Democratic boss Meade Esposito, a close associate of Paul Vario, who was the basis for Paul Sorvino’s character in Goodfellas. None of this is terribly exceptional: To do business in New York at that time, particularly in construction, you were gonna have to deal with the mob. That’s just how things worked. And that was Trump’s education in political philosophy, as it were: “This is how things work.” Everything’s a racket: You’re either on the outside, a chump, or on the inside, making it.

Mafias and the like are secret societies. Rackets work for a closely knit in group that exploits an outgroup. But what Trump offers is the clubbiness of the mob for the masses. He offers a big hug and a kiss. He brings you into his “family:” “I’m gonna tell you how it really works and with me you’re gonna be rich and powerful. And fuck everyone else.” He offers protection: as “Jonathan” remarks, he’s “the guy who does bad things but does them on behalf of the people he represents.” He might kick the shit out of the other guy, but to you, the guy on his side, he’s warm, gregarious, and fun: he winks and slaps you on the back.

For these voters, the “system” has failed, so we need Trump. But what is the system? Basically all the universalistic promises of liberal democracy, be they the notion of the rule of law, formal political equality, or market exchange. In all of those frameworks, individuals are supposed to encounter other individuals as free and equal citizens endowed with the same inalienable rights. A harmonious society supposedly develops from the interplay of their diverse interests. But what if it doesn’t? As Marx once pointed out, in capitalist society, “under [the] “rule of law”, the law of the jungle lives on under a different guise.” To many, life feels more like a continuous struggle for survival rather than a social contract providing for reciprocal rights and obligations. Margaret Thatcher once said, “There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.” What Trump says, in effect, is, “There is no such thing as society. There are rackets. And I can help you get in on one.” And, as a corollary, “There are no contracts. There’s what you can get away with.”

This is the key difference between Trumpism and traditional conservatism, which still paid lip service to minimal, formal universal mediums like the rule of law, citizenship, and the market. To Trump those words are just bullshit, the nice sounding lies of the big shots, the pezzonovante as Vito Corleone calls them. In the Trumpanschauung, society is not some meritocracy where there’s sportsmanlike competition and everyone gets a fair crack. No, it’s a nasty, brutish place where sometimes you have to be “not very nice,” as he likes to say. “Racket connotes a society in which individuals have lost the belief that compensation for their individual efforts will result from the mere functioning of impersonal market agencies,” as the Frankfurt School political theorist Otto Kirchheimer once wrote.

Even if society is not experienced as a daily war of all against all, it can still be lonely, alienating place, where atomized subjects seek out small advantages and find little in the way of warmth or solidarity. With the failure of impersonal social agencies, people want to return to personal rule. Trumpism offers the appearance of a solution: Rackets don’t just take care of the material wellbeing of the insiders, they are always also sources of recognition and belonging. You’re part of the clan, the crew, the family. The “fuck you” of Trumpism, its “shock to the system,” might appear to be purely anti-social, a rejection of the reciprocal norms that make cooperative social life possible, but it’s in point of fact pre-social, it speaks to the longing to a return to something earlier, “the original closeness of blood,” something more organic than society: the gang, the mob, la famiglia — to Gemeinschaft.

In a 1992 essay about Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, the paleoconservative intellectual Samuel Francis and theorist of Trumpism avant la lettre, opposed broader American society and the Corleone family using the German sociologist opposition between Gemeinschaft, community, and Gesellschaft, society:

America…does not behave like the Corleone family after all, and the differences between the two societies do not favor America. The differences between the two are precisely those between two kinds of social organization that sociologists describe as Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft respectively. Gemeinschaft refers to a kind of culture characteristic of primitive, agrarian, tribal societies, in which bonds of kinship, blood relationship, feudal ties, social hierarchy, deference, honor, and friendship are the norm.

Gesellschaft, on the other hand, represents modern social organization, dictated by rationality, calculation, self-interest: “an essence expressed in such modern organizations as corporations (for which Gesellschaft is the German word) and the formal, impersonal, legalistic, bureaucratic organization of the modern state.” Francis relished the The Godfather’s “slap in the face” of “the favorite American myth that through assimilation into the institutional environment offered by the democratic capitalism of the American Gesellschaft, human beings can be perfected and force and fraud as enduring and omnipresent elements of social existence can be escaped.” Trump, this soi-disant Godfather, is a similar slap in the face of the dreams of American liberalism. In its place, we have the rule of the Don. (This is also what sociologist Dylan Riley is referring to when he talks about Trump’s “patrimonalism,” his tendency to run things as if they were extensions of his household and family business.)

Although on the surface there might seem to be a big split between those who view Trump as racketeer, as Al Capone, the bandit king, and those who hope for him to become a Caesar, Duce, or Führer, but they are essentially the same phenomenon. The fascist chieftain says to his subjects, “This world of advancing civilization through free trade, international organizations, agreements, and cooperation, or that of socialism, with its brotherhood and the solidarity of man, these are all lies, designed to fool you. Here’s the truth: There’s our kind of people, and then there’s their kind of people, and we will make sure to get ours—at their expense.” They dissolve the world into “a diffuse barbaric plurality,” as Franz Neumann once wrote of the Nazi state. In the place of universal conceptions like citizenship or humanity, the fascist chieftain and the mafioso present their own false universalisms, or particularistic replacements for universal categories, like the (tribal) nation, the gang, the family, or, the race. Of course, this is an illusion.

Trump may not bring an end the American republic or start a civil war, but we might reflect that with him we gave up even on the pretense of a public spirit that could arise through democracy and just let ourselves be ruled by the mob.

This is really good. I've been saying to others since 2017 or so that Trump's moral universe is both pre-modern and that of a mob boss. More vaguely, I've always felt his vibe is very much that of Mid-Atlantic suburban (ethnic) conservatism, which I suppose has more than some overlap with the kind of people who were in or close to the mafia in the 1970s and 1980s. Like I get it might be a horrible stereotype, but the people in Goodfellas (and not just the made men and their violent accomplices) always seemed to me like Trump's base. Maybe not surprising Giuliani has become one of his most deranged supporters (ironically Giuliani was an anti-mafia crusader during the 1980s - I think he features prominently as a talking head in the Netflix doc "Get Gotti")

What is more interesting is the degree to which Trump has succeeded in getting (evangelical) Protestant small town America to totally buy into this ethic. Like I didn't necessarily see the world of Goodfellas (politically) conquering the world of America Gothic at all. A lot more to explore there.

Unfortunately the inchoate anger that led so many to vote for Trump, in order to give the middle finger to "the system," doesn't allow them to see that the alternative to the "the system" would in all likelihood make them much worse off. Of course the American system is unfair to less affluent people and is trending toward oligarchy, but Trump would only accelerate that trend or just lead to anarchy and a Hobbesian nightmare. Why short-sighted billionaires can't see that they, too, would be worse off if the system devolves is beyond me.