What It Took To Win

Thoughts on Zohran Mamdani's Popular Front

The old saw goes that politics is the art of the possible, but it often seems like the art of the impossible: putting together winning coalitions that “objectively” seem to defy logic—or at least, the logic of the pundits.) My favorite example of this is Trump managing to spike the white working class vote and fulfilling the longtime Republican dream of expanding their vote with minorities that had always stuck close to the Democrats. We were told

(and I also believed, regretfully) that Mamdani’s positions on Palestine would be too alienating for Jewish Democrats, although there was strong reason to believe that Israel had become increasingly unpopular, even—and perhaps especially—among Jewish liberals. We were told repeatedly by the punditocracy that the Left was to blame for everything, and the defection of minorities and middle-class immigrants had to do with anti-wokeness and reaction to “defund the police” rhetoric after George Floyd. And we were told there was a realignment in the offing: a long-standing shift of the middle- and lower-classes to the right. But there was good reason to believe that the choice of Trump, especially by many new Republican voters, was less about a specific grievance than a general protest, an anti-system vote. And if there was one shared problem, it was that life post-pandemic just felt stagnant and unprosperous, due in large part to inflation.

The lesson Mamdani and his strategists evidently took from the presidential election and the return of Trump was that the weakness of the Democratic establishment with its traditionally loyal constituencies signalled an opening for another kind of protest politics entirely, one that was constructive and positive, rather than rancorous and divisive. Those groups had not been permanently seduced by the right so much as not mobilized and activated by a progressive alternative. And they noticed there was an entire universe of motivated voters (and, importantly, volunteers) out there just waiting to be reactivated: Veterans of Bernie 2016, 2020, Warrenistas, and all the civic movements of the 2010s who had not given up but were simply dormant, waiting for new leadership. Then he diligently added to this base.

What I found particularly notable is Zohran’s outreach to small business owners, which in New York, contains a lot of recent immigrants. Rather than treat them as “petit bourgeois reactionaries” ensorcelled by Trump’s politics of resentment, his campaign saw them as small-d democrats who were not wedded to either party. This goes back to Mamdani’s early advocacy for Taxi medallion holders. This is a real popular front strategy in the oldest sense of the term: an alliance of the democratic middle class and the working class. (And I will point out that he used a bit of anti-fascism here and there as well. :)

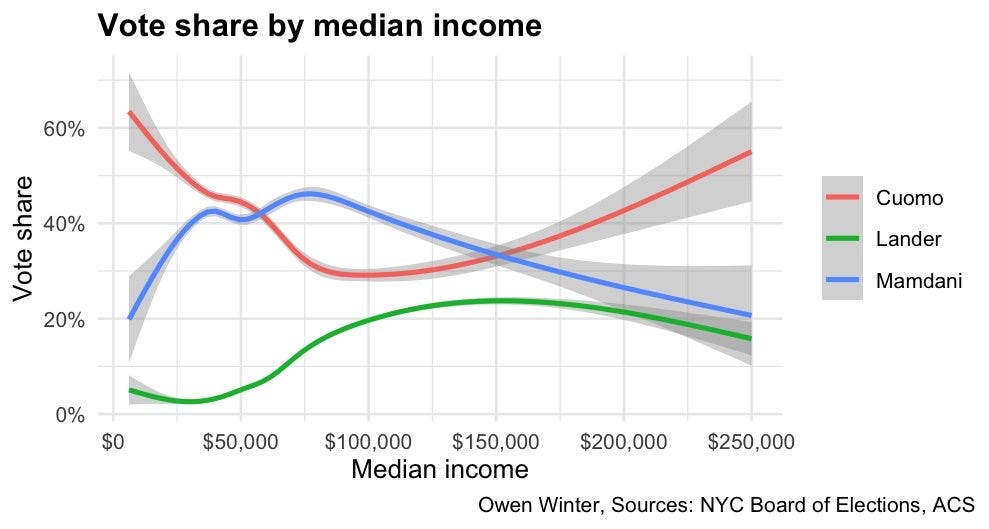

Now, the class stuff needs to be qualified a bit. I’m sure if you’ve seen the infographic from The Times that shows Mamdani doing best among voters making over 100k. This has led to the familiar right-wing attacks on the “luxury beliefs” and the supposed spiritual sanctimony of progressive voters winning out over their material interests. But this is misleading and, in many cases, deliberately propagandistic. I’m going to break a house rule and include a chart:

As you can see, Cuomo did well among the very rich and the very poor. Mamdani does well in the middle, which in New York, with its high cost of living, stretches well into the six figures. High-five and six-figure income includes a lot of unionized wage laborers, junior white-collar professionals, and small business owners. Say what you like about their feasibility, the major policy portions of Mamdani’s campaign were about cost-of-living issues, and he targeted a coalition that goes across cultural and racial backgrounds but were all struggling to build decent lives in New York.

Ranked choice voting also played a part, and the alliance of Brad Lander must be taken into account as a key part of the popular front. Lander is a representative of an older New York political tradition than Mamdani’s: Jewish left liberalism. Both Lander and Mamdani realized that these political traditions made better allies than enemies, with demonstrations of the candidates’ grace and solidarity that both liberals and leftists should note well. There’s also a class dimension here: Lander did well in highly educated sections of the city and then basically fell to zero in areas with lower rates of higher ed. But Zohran did not: even when he could not outdo Cuomo, he still kept pace.

I want to say something here, too, about the constant introduction of the Israel-Palestinian conflict into the race. There clearly was an effort to smear Mamdani with Jewish voters as an antisemite, and it just didn’t work. The guy just does not come across as a hateful person. Also, New York has a population about the size of Israel, except compared to them, we are practically a utopia, where people of very different backgrounds live peacefully (if grumpily) side by side. Let’s not introduce ethnic hatreds into a place where they are largely successfully overcome. And let me tell you a little secret: most New York Jews really like New York’s diversity. We like that it attracts the Mamdanis of the world. We like sharing it with people of lots of different backgrounds. That’s what makes us feel safe and happy here. Especially when they are such a mensch like him: a nice college boy, his parents are a professor and a filmmaker, he went to Bronx Science, and then to a liberal arts school. I’m sorry, but you are gonna have a hard time convincing liberal educated, upper-middle-class Jews not to like a college-educated, left-leaning immigrant—and one who tried to make a career in the arts?! Forget about it. The guy is practically Jewish! Not to mention that his Muslim and Indian identity is no doubt sincere, but it’s also largely cultural in a way a lot of Jews recognize.

Something else needs to be said about the Mamdani’s “M” and the Cuomo’s U” on this chart. It reflects Old New York vs. New New York and therefore two different forms of civil society. Mamdani captured more recent arrivals in New York, across cultural and class lines: post-college professionals on the make (or, in many cases, downwardly mobile white-collar workers who are being proletarianized or bohemianized) and recent immigrants from abroad. Cuomo appealed to the old gentry and business oligarchy (now more Wharton School than Edith Wharton) on the Upper East and West Sides and the old working class in the outer boroughs. And in many cases, they are quite literally old: the youth broke strongly Mamdani. But they also represent an earlier form of social organization: Cuomo campaigned at union halls and churches. Traditionally, these are good places to meet the electorate. But the clear lesson of the past decade was that the old civic associations’ power to control and mobilize the electorate has been steadily weakening. Remember that the “machine” as it is called, was built in another epoch; it pre-dates even the labor union, the radio, and television! It has survived in an etiolated form but is no match for the instantaneous powers of communication available in our era. Machine bosses were considered a throwback already by the 1970s. In his entitlement and laziness, Cuomo thought this tenuous structure would be enough. It wasn’t. It simply doesn’t serve or talk to enough voters anymore. The machine broke down because it’s old and rusty.

Mamdani mastered the new and dominant form of civic association: the Internet. But he also did politics in a very old-fashioned way; he met people in person, in unmediated settings. Lots of hitting the sidewalk and shaking hands. Lots of talking to voters. I said this after Harris’s loss: Sure, the media environment is changing. Yes, the electorate is changing. But politics is ultimately about speaking in public. Find someone with powers of self-expression and you're in business. And Mamdani is a great public speaker. Simple, strong rhetoric wins the day: “Dont. Rank. Cuomo.” Let’s also not discount the fact that he’s just young and good-looking, and Cuomo looks and acts like a creep.

The problem with the polling and all the emphasis on data in contemporary politics is that it does not take into account that the electorate doesn’t really exist until election day, and the politician and his or her campaign are actively creating that electorate. All political errors, from the level of action to analysis, are based on reifying the situation, believing in a static, factual reality that cannot be changed. And all great political successes are based on the opposite: the art of the impossible; believing in a chance for something new.

I hope you were real pleased with yourself about that Wharton School/Edith Wharton line.

“the guy is practically Jewish” — i’ve certainly seen a bunch of posts calling him some version of rootless cosmopolitan