Wit and Alienation

"Esprit," Ridicule, and Enlightenment

Maybe because I’m currently obsessed with French history, I recently re-watched the movie Ridicule (1996), which is about a young idealistic nobleman on the eve of the French revolution. He travels from the provinces to Versailles in order to get royal support for a drainage project on his swampy land to help his peasants who are getting sick. He applies to the bureaucracy, but finds it’s not the real power center at Versailles. The court is where favor is dispensed and access to the court and royal favor is governed through a peculiar type of merit: the ability to demonstrate esprit. The word esprit is notoriously hard to translate, it’s obviously a cousin of “spirit” but in this context is closer to “wit.” According to Benedetta Craveri in her book The Age of Conversation, esprit “embraces a vast gamut of meanings, from spiritual, intellectual, and speculative to witty, ironic, and brilliant.” Things that show a liveliness of mind can be said to have esprit. To access the court through the various glittering salons of aristocrats, one has to be witty. Often, this comes at the expense of other aspirants: humiliation is a key weapon in this witty struggle of all against all.

In the film, the young Baron is taken in by an older Marquis who guides him through the world of Versailles and he gets lost in the corruption of the court and forgets his true purpose, but, through love of a virtuous woman, the Marquis’ daughter… Anyway, you get the point. The movie is not that great on the level of plot, but it’s interesting to see the world it describes on film. It’s a place where being clever and cruelly penetrating is the way to get ahead. It reminds me a little bit of the dynamic on Twitter, where the making of clever remarks—often at the expense of others—is the coin of the realm. In the movie, there’s a scene where the king is being told the witty remarks each of the courtiers is known for, almost as if he was being told their Tweets. Of course, in the salon and the court of Versailles, the object was access to actual power and wealth, but the powerful and rich are only interested in demonstrating their esprit, so playing the game becomes an object in itself.

The problem is that this world of esprit is based not on any kind of substance or tradition, but on pure insight, self-reflection and superior self-consciousness. Witty remarks that have to lay bare what’s actually going on to function, and so the wits will begin to eat away at the very system that sustains them.

In the Phenomenology of Spirit, there’s a section entitled “The World of Self-Alienated Spirit” where Hegel interprets Diderot’s dialogue Rameau’s Nephew. Diderot was an Enlightenment philosophe, no stranger to the world of the salon. In the dialogue, Rameau, the nephew of a famous musician, talks to a character only known as Moi, myself, who embodies good common sense and morality. (It is to be understood he is also of self-sufficient means.) The nephew on the other hand is a kind of parasite on the world of the salon: he auite literally lives by his wits, entertaining the rich aristocrats and bourgeoisie by making a fool out of himself. His perspective is perverse and satirical: he sees that all the values of the aristocratic world are actually vain and empty. He grifts from the rich, but knows they are no better than him. His speech is “sparkling,” “witty, spirited”:

The content of spirit’s speech about itself and its speech concerning itself thus inverts all concepts and realities. It is thus the universal deception of itself and others, and, for that very reason, the greatest truth is the shamelessness in stating this deceit. This speech is the madness of the musician “who piled up and mixed together some thirty airs, Italian, French, tragic, comic, of all sorts of character; now, with a deep bass, he descended into the depths of hell, then, contracting his throat, with a falsetto he tore apart the vaults of the skies, alternately raging and then being placated, imperious and then derisive.”

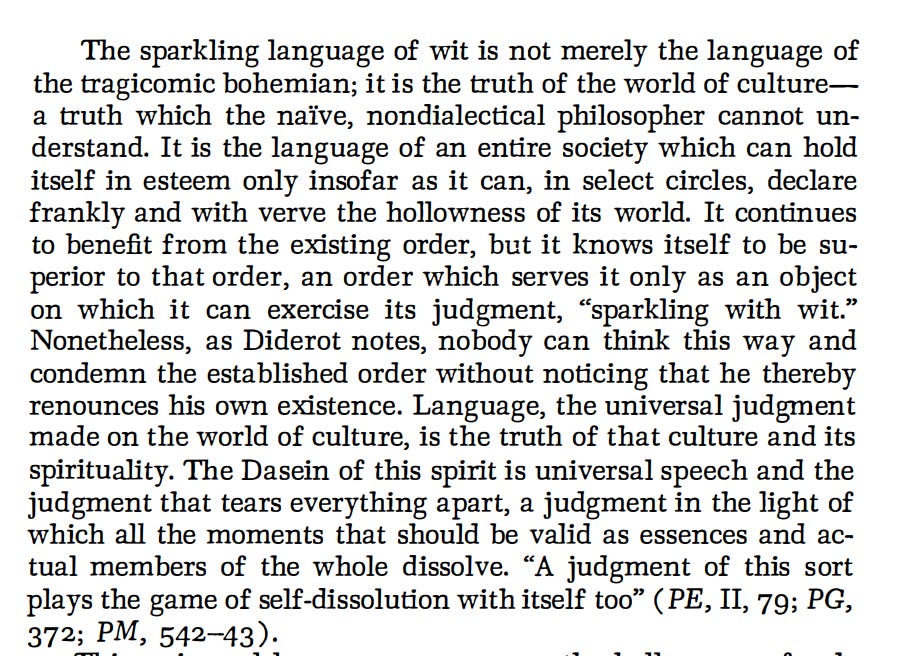

In contrast the honest consciousness of the philosopher only hits “one note.” As Hyppolite puts it in his commentary on the Phenomenology:

The nephew is just the final expression of the culture of esprit, the witty remark turned back on itself—he has seen through all the bullshit, including his own:

The realization of the hollowness of the society, this new form of self-consciousness creates a problem: if we all know culture is alienation and “this world is bullshit,” to quote Fiona Apple what do we do next? The two—apparently opposed but actually united —solutions to the problem of self-consciousness poses to itself are Faith and Enlightenment. But I’ll have to get to those another time.