An Attempt at Intellectual Fraud

Phil Magness is Full of Shit—Again

In The Journal of Political Economy, Phil Magness of the American Institute for Economic Research and Michael Makovi of Northwood University, have a paper entitled “The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the Effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s Influence.” The article attempts to use Google ngram analysis to make the case that Marx was a “a relatively obscure figure in his own lifetime” with little or no influence on academia before the Russian Revolution, which the authors label a “political happenstance.” According to the authors, academic interest in Marx spiked only after the Revolution as people sought to understand and respond to it. This is somehow supposed to diminish Marx’s intellectual significance.

First of all, this is a very strange argument on the face of it: they are essentially saying, “He was never respected in mainstream academia, he only inspired a massive, world-shattering historical event.” It’s a trivial and unsurprising discovery that after the revolution interest in Marx would grow. The parochialism on display here is risible: the authors seem to believe only academic citations within their discipline are important, all that stuff happening in the real world, that’s just “political happenstance” as they put it. Another aspect of parochialism is that the authors seem to believe that intellectual culture and academic standards are identical from one era to another, and that therefore The Citation is the gold standard of intellectual significance for all time. So what are they on about exactly?

The paper manages to be both false and self-contradictory from the very first sentence: “In the decades following Karl Marx’s death in 1883, the socialist economist’s theories fared poorly under the scrutinizing eyes of the discipline he sought to reshape through his magnum opus, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy.” Again here we witness the laughable parochialism of the authors: Marx had no ambitions to reshape the discipline of economics, which he believed was built on flawed premises and essentially served as a system of justification for capitalism. Marx was not trying to get tenure or get into journals. As he famously wrote in the Theses on Feuerbach. “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.” Marx’s Capital is a critique of economics, meaning it is directed against the discipline’s underlying presuppositions. The goal was to replace economics with an entirely different science and also contribute to the building of a worker’s movement that would ultimately overthrow capitalism.

The question, then, is why, if Marx was really such a marginal and unimportant figure as Magness and his co-author would like us to believe, he even attracted the “scrutinizing eyes” of their discipline? Why would the great Böhm-Bawerk pay attention to this crank, back in 1902 no less? Well, the answer is in Böhm-Bawerk’s words right there in their own paper, albeit squirreled away in a footnote: “Marx[’s theory] is the one which has won most general acceptance, and the one which may to a certain extent be regarded as the official system of the Socialism of to-day.” The authors then just wave this away: “While this speaks to Marx’s stature among socialists at the turn of the century, it does not explain his outsized prominence in the social sciences today, which is our primary concern.”

Böhm-Bawerk’s comment highlights to the intrinsic flaw in this quantitative method of pointing to the sheer amount of academic mentions of Marx as an indication of his intellectual significance. What, if for example, those few mentions were, like Böhm-Bawerk’s, to the effect of “this Marx guy is important?” That is what Max Weber, a critic of socialism, said to his students towards the end of his life:

The honesty of a scholar of our time, and even more of a philosopher of our time, can be judged on how he described his own relationship to Nietzsche and Marx. He then who denies that he would have been incapable of achieving the most important parts of his own work without heirs belies himself just as much as others. The world in which we live as intellectuals, bears largely the imprint of Marx and Nietzsche.1

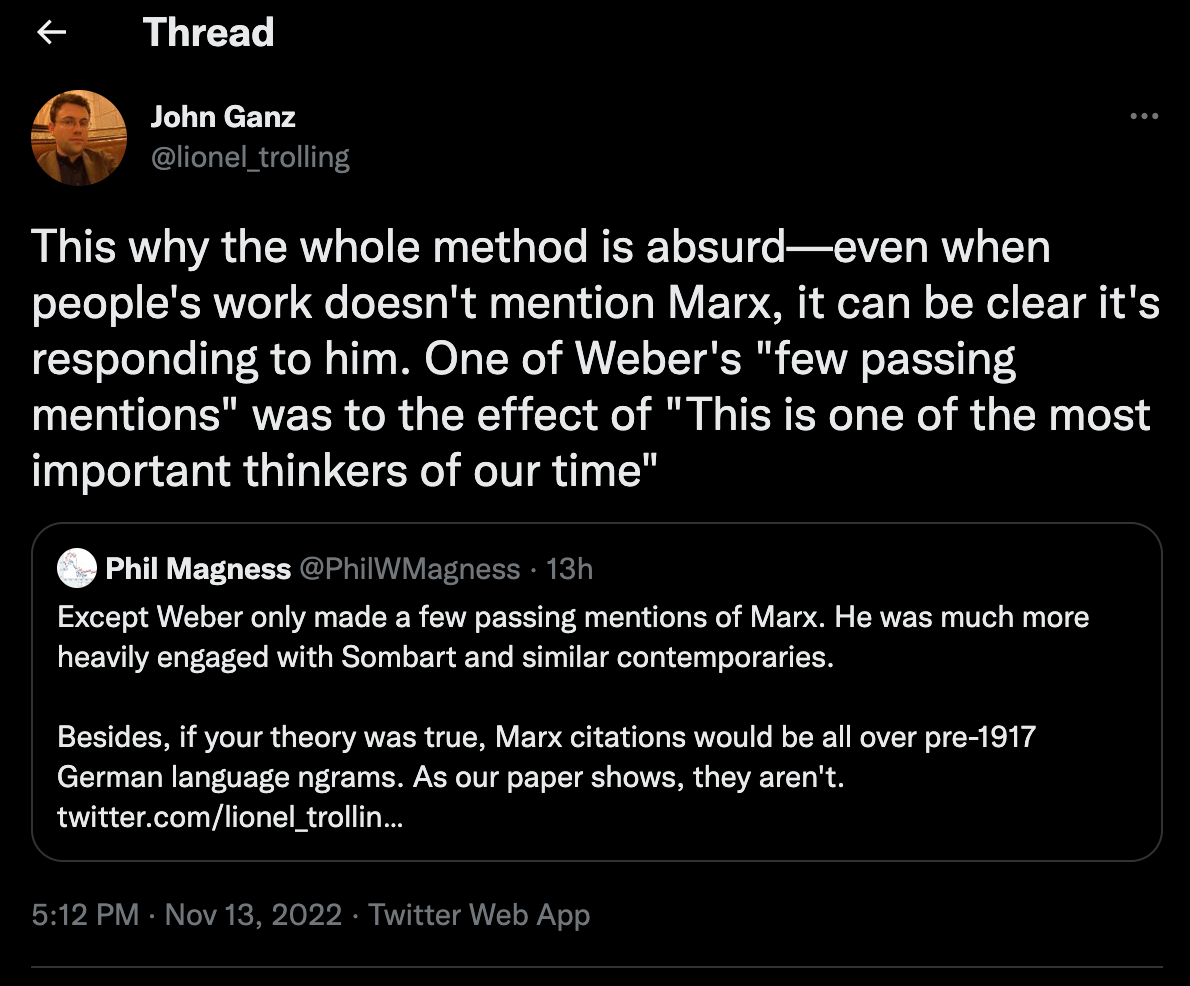

(I need to insert an unfortunate sidebar here: Magness is falsely claiming on Twitter I said that these comments appear Weber’s The Protestant Ethic. Magness is either lying or hopelessly befuddled: I never said these comments were in that book, because I know they are not. He said Weber made only a few passing mentions of Marx. I wrote that the mere frequency of mention was an absurd criterion, because someone could make reference without naming someone directly and/or even those few references could be quite strong. Here’s what I wrote: )

Émile Durkheim, another of the founders of classical sociology and major intellectual figure at the time, also took Marxism seriously as a doctrine, even when differing from it. In a 1897 review of the Italian Marxist Antonio Labriola’s book on historical materialism, Durkheim wrote, “We believe it is a fertile idea that social life be explained not by the conceptions of those who participate it, but by profound causes which escape consciousness.”2 And here we arrive at another flaw with the method: it’s clear that Marx had already suffused the intellectual culture to such a degree that he had a) major followers like Labriola who produced work in his own right, b) produced a recognizable set of ideas that could be addressed without mentioning his name directly.

Thorsten Veblen, another major figure in the social sciences of the time lectured on Marx at Harvard in 1906, saying “the system as a whole has an air of originality and initiative such as is rarely met with among the sciences that deal with any phase of human culture.”

What else can attest to the intellectual importance of Marxism in this era of the Second International, prior to the Revolution? Let’s try intellectual historian Leszek Kolakowski, a fierce critic of Marxism:

Marxism seemed to be at the height of its intellectual impetus. It was not a religion of an isolated sect, but the ideology of a powerful political movement; on the other hand, it had no means of silencing its opponents, and the facts of political life obliged it to defend its position in the realm of theory.

In consequence, Marxism appeared in the intellectual arena as a serious doctrine which even adversaries respected. It had redoubtable defenders such as Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Plekhanov, Lenin, Jaurés, Max Adler, Bauer, Hilferding, Labriola, Pannekoek, Vandervelde, and Cunow, but also such eminent critics as Croce, Sombart, Masaryk, Simmel. Stammler, Gentile, Böhm-Bawerk, and Peter Struve. Its influence extended beyond the immediate circle of the faithful, to historians, economists, and sociologists who did not profess Marxism as a whole but adopted particular Marxist ideas and categories.3

Magness’s paper also tries to downplay the significance of Marx on the labor movement and political socialism prior to the Russian Revolution, citing a number of “competing traditions” that were crowded out by Soviet Marxism. But the fact of the matter is that the mass social democratic parties of Western Europe were substantially Marxist prior to the Russian Revolution. Kolakowski again: “Although non-Marxist traditions of socialism had not lost their strength (Lasalleanism in Germany, Proudhonism and Blanquism in France, anarchism in Italy and Spain, utilitarianism in Britain), it was Marxism that stood out as the dominant form of the workers’ movement and the true ideology of the proletariat.”4 The German Social Democratic Party’s 1891 Erfurt Program was explicitly Marxist, written in part by the ultra-orthodox Karl Kautsky. At the same time, the SPD was also the single largest party in the Reichstag. In 1912, the SPD won nearly 40% of the vote. The two major French socialist leaders of opposing tendencies, Jules Guesde and Jean Jaurès, were both Marxists. Although it would make it easier for the authors of this paper to tar Marxism as a doctrine of sheer blood-thirst, the fact is that the Bolsheviks never had a complete monopoly on Marxism: non-Communist socialist parties existed in and, at one time or another, governed just about every Western European country up to the Second World War.

One other major factor has to be acknowledged here in terms of the citation issue and one that the paper just totally neglects to mention: Bismarck’s 1878 anti-socialist law that banned social democratic groups and shuttered socialist publications. In fact, there is no consideration on the effect of press censorship in Imperial Germany on the presence or absence of ngrams. Do the authors even know this history? I highly doubt it.

The political motivation for the paper becomes clear with the conclusion:

our findings renew the challenging questions on how to interpret Marx’s reputation in light of its inextricable connections to the Soviet Union’s troublesome historical record. While much of the discussion surrounding the bicentennial of Marx’s birth sought to differentiate consideration of his modern relevance from the totalitarian track record of twentieth-century communism, the elevation of Marx’s stature provided by the Russian Revolution illustrates that the two cannot be easily separated. It is insufficient to portray Soviet communism as an aberration from true Marxist doctrine, as the intellectual mainstreaming of Marxist theory is intimately intertwined with the political establishment of the Soviet Union. In assessing how this historical link shapes current interpretations of Marx, one must grapple with the implications of Marxism’s early twentieth-century intellectual ascendance as a Soviet political project.

The entire purpose here is to chain Marx to the Soviet Union and thereby to “totalitarianism.” This is not meant to be a serious exercise in intellectual history, it’s a piece of demagogy, a political attack mimicking the methods of the social sciences to make the dogmatic case that “Marx = Soviet crimes.” The authors are apparently totally incurious about the intellectual or political culture of the era in question, just want to gather enough information and make enough caveats to launder their claims through the appearance of serious scholarship. Whatever your opinion of Marx and Marxism, the notion that there was no “mainstream” interest in Marx prior to the Russian Revolution is simply false: in both the intellectual world and politics, Marx was already a major figure, someone the great intellects of the era felt they had to wrestle with, and the guiding theoretician of mass political parties in Europe. While it is true Marxism was not really an academic tradition during this time, it was very much part of a public intellectual world: Kautsky’s articles, read by hundreds of thousands, were much more “mainstream” than the academic economists of the era. I would wager a good deal of money that the name “Marx” was then known a great deal more to the public than “Böhm-Bawerk” or Jevons or Menger or whomever you like. With these facts in mind, it’s difficult to conclude that this paper is anything but an attempt at intellectual fraud through methodological chicanery.

Mommsen, W. J. (1977). Max Weber as a Critic of Marxism. The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, 2(4), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/3340296

Therborn, G. (1976). Science, class, and society : on the formation of sociology and historical materialism. London: NLB. 251

Kołakowski, L. (1981). Main Currents of Marxism: The golden age. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2

Kołakowski, L. (1981). Main Currents of Marxism: The golden age. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 11

Ha! Perhaps everyone should have the privilege of writing a delicious takedown of Magness like this. Here’s mine from a few years ago: https://academeblog.org/2017/04/11/on-blacklists-harassment-and-outside-funders-a-response-to-phil-magness/

Just brilliant. Thanks. As footnotes, you could add Samuel Gompers and Frederick Jackson Turner to your pantheon--old Sam always claimed he was a Marxist, and young Fred cited Achille Loria, another famous Italian Marxist (Gramsci cited him, too) in making the frontier significant in American historiography.