Dingbat Imperialism, the Lowest Stage of Capitalism

Reading Lenin Today

Many commentators have noted that Trump’s conduct in foreign affairs is as if you took the most simplistic and reductionist left-wing critiques of American foreign policy and decided what they described—a rapacious, oligarchical empire systematically stripping poorer and smaller nations of their resources—was what we should be doing. Matt Yglesias recently tweeted about a Trump post where he described a system of American companies dumping surplus goods into a pliant Venezuelan market: “This is like Lenin’s account of imperialism, but with ‘— and that’s good!’ added to the end.” The natural riposte to this line of thought is perhaps that the left-wing critiques of American imperialism weren’t so stupid after all, and Trump just has the bad manners to tell the truth. And you could just as easily imagine an impatient liberal response to some on the anti-alarmist left in reply: “Here is the guy who is actually what you said America was all along: a vulgar fascioid businessman who is using state power to enrich himself and his friends, but for some reason he offended and worried you less than the other guys.” But rather than attend to this squabble, I’m actually curious about how well Lenin’s account of imperialism fits what Trump is doing or trying to do.

Interestingly enough, “Lenin’s idea of Imperialism, but we should do it,” is pretty much how Vladimir Putin thinks, if you take the word of his former advisor Gleb Pavlosky:

It was a game and we lost, because we didn’t do several simple things: we didn’t create our own class of capitalists, we didn’t give the capitalist predators on our side a chance to develop and devour the capitalist predators on theirs…Putin’s idea is that we should be bigger and better capitalists than the capitalists, and be more consolidated as a state: there should be maximum oneness of state and business…

This makes sense, since Putin would’ve had Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy drilled into him in his training as a KGB officer. But what is the Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy on imperialism exactly?

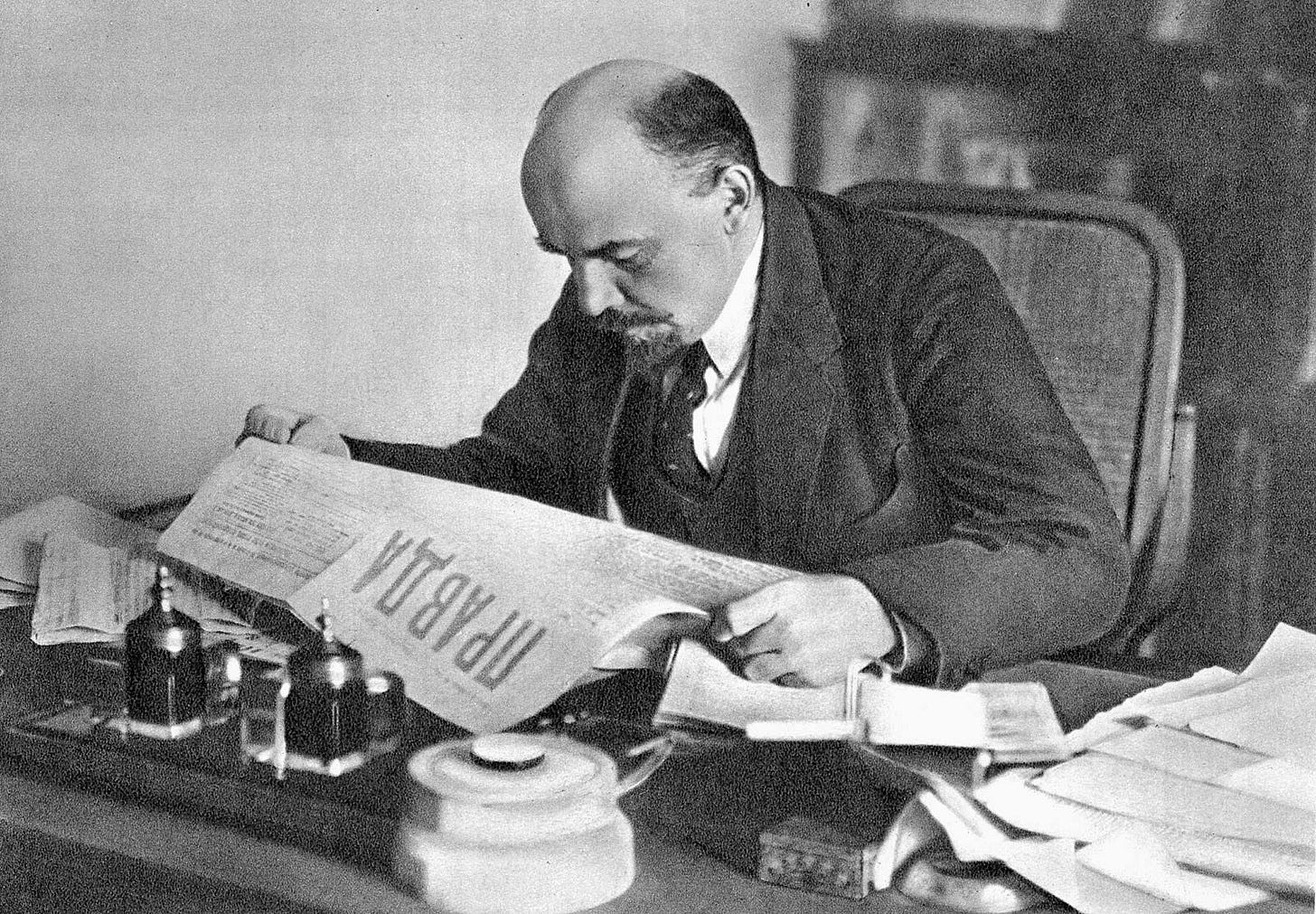

Vladimir Lenin’s pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism was written during the First World War. Subtitled “a popular outline,” it was meant to explain to the working class the nature of the war taking place and to polemicize against the reformist, “opportunist” socialist and social democratic parties, that, in many cases, had gone along with it, and that Lenin believed were inextricably tied to the imperialist system. It’s not a fully developed theory nor is it entirely original: it’s largely based on the works of the Marxist Rudolf Hilferding and the liberal J.A. Hobson, and is directed against the earlier theories of Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg. It was written in the heat of battle, as it were: Lenin was struggling to win over the European proletariat to his vision of world revolution. But it is a work of bold vision and compelling claims.

Lenin writes, “the briefest possible definition of imperialism we should have to say that imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism.” According to Lenin, capitalism has left behind its old liberal, laissez-faire competitive mode; the process of competition itself has given rise to monopoly as the winners devour the losers. Industry has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few great cartels, and these cartels, requiring vast supplies of credit for their operations, come under the control of banks. This combination of heavy industry and banking Lenin calls “finance capital.” In the pamphlet, he quotes Hilferding to describe the nature of this finance capital:

“A steadily increasing proportion of capital in industry…ceases to belong to the industrialists who employ it. They obtain the use of it only through the medium of the banks which, in relation to them, represent the owners of the capital. On the other hand, the bank is forced to sink an increasing share of its funds in industry. Thus, to an ever greater degree the banker is being transformed into an industrial capitalist. This bank capital, i.e., capital in money form, which is thus actually transformed into industrial capital, I call ‘finance capital’.” ….“Finance capital is capital controlled by banks and employed by industrialists.”

This financial oligarchy, seeking profitable investments in shrinking markets it already dominates, seeps into the nation-state itself and directs it to look abroad, grabbing colonies. The world becomes divided up by big monopolies with the help of their pliant government hosts. Lenin helpfully breaks this down into four points:

(1) the concentration of production and capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life; (2) the merging of bank capital with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this “finance capital,” of a financial oligarchy; (3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance; (4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist associations which share the world among themselves and (5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed. Imperialism is capitalism at that stage of development at which the dominance of monopolies and finance capital is established; in which the export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun, in which the division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed.

I want to focus on these, particularly number 3, but first, we have to answer why Lenin calls imperialism “the highest stage of capitalism,” by which it often appears he means the last stage. For Lenin, monopoly capitalism is almost socialism; the concentration and socialization of production have happened, and it just remains in private ownership:

Competition becomes transformed into monopoly. The result is immense progress in the socialisation of production. In particular, the process of technical invention and improvement becomes socialised….

Capitalism in its imperialist stage leads directly to the most comprehensive socialisation of production; it, so to speak, drags the capitalists, against their will and consciousness, into some sort of a new social order, a transitional one from complete free competition to complete socialisation…

Production becomes social, but appropriation remains private. The social means of production remain the private property of a few.

The capitalists have done the socialists a great favor by organizing things like this: it makes the seizure of the means of production much easier! But as Lenin and Hilferding both thought, the jockeying for domination of the world by these combines would tend towards war between the imperialist powers. This created another opportunity for the militant working class. As Hilferding put it in his 1910 Finance Capital, "the policy of finance capital is bound to lead towards war, and hence to the unleashing of revolutionary storms.” As I’ve written about before, this is contra Kautsky, who imagined the possibility of intermonopolist cooperation and a peaceful transition to socialism.

In 1917, Lenin’s account of the world looked pretty plausible. There was, in fact, a war raging between the imperialist powers, and soon, revolution would break out, first in Russia, and then all over Europe. But how well does Lenin’s Imperialism explain today, in particular, Trump’s neo-imperialism in Venezuela?

The first thing to note is the anachronism of Lenin’s picture of monopoly capitalism. Yes, there is the word “finance” there, but finance capital is not identical with “financialization,” as we’ve come to know it. For all the rentier and “parasitic” behavior Lenin describes in the imperial core, he emphasizes the importance of capital exports, that is to say, of fixed capital, machinery, and plant. The world we are dealing with there is much more “steampunk,” if you’ll permit me. As I quoted above, “the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance.” This is because the capital’s rate of profit is sagging in the core. Trump’s vision of dumping commodities into Venezuela doesn’t fit that model. In this case, the big capitalist combines, the oil cartels, really don’t want to invest capital abroad. They are doing fine, thank you, and don’t really want to sink all this fixed capital into the mire of Venezuela. It’s not some easy colonial backwater ripe for the picking, but a very tumultuous and unstable environment, and they’ve been burned before. While other big oil company execs appeared ready to humor Trump, ExxonMobil’s CEO was frank: he called Venezuela “uninvestable” without major changes. As a result, Trump threatened to block them. But, of course, they don’t wanna go anyway! Even a close backer of Trump like oil tycoon Harold Hamm has “declined to make commitments,” while making some superficially enthusiastic noises. When the oil bosses asked for guarantees, Trump said he would guarantee their security. But he’s not gonna be around forever! We’re talking multiple-year investments. To make matters more difficult, the type of crude in Venezuela is tough and costly to refine.

So, Lenin’s vision of the financial oligarchy finagling the government to fund adventures abroad? Not quite the case here. Here we have the government trying to finagle the cartels. To be fair to the Leninists, Vladimir Ilyich makes clear that the foreign intrigues of the monopolists are often “secret” and “corrupt” manipulation of government, so we may not have the full picture. And perhaps there is a different dynamic in the case of raw materials and extraction. Lenin writes:

The principal feature of the latest stage of capitalism is the domination of monopolist associations of big employers. These monopolies are most firmly established when all the sources of raw materials are captured by one group, and we have seen with what zeal the international capitalist associations exert every effort to deprive their rivals of all opportunity of competing, to buy up, for example, ironfields, oilfields, etc. Colonial possession alone gives the monopolies complete guarantee against all contingencies in the struggle against competitors, including the case of the adversary wanting to be protected by a law establishing a state monopoly. The more capitalism is developed, the more strongly the shortage of raw materials is felt, the more intense the competition and the hunt for sources of raw materials throughout the whole world, the more desperate the struggle for the acquisition of colonies.

What the oil companies might like is a “complete guarantee” of a colonial situation, but they seem skeptical that Trump can really provide that. But is there a shortage in this case? On the contrary, there is a bit of a glut in oil at the moment, although the lack of investment might contribute to a future shortage. Analysts say that even a major crisis in Iran—imagine such a thing!—would not seriously affect global supply.

Now, a Leninist might object that I’m misreading the text in too conspiratorial a way and that I have to take into account a structural impulse built into financial capital to force investment. But if anything, we’ve seen financialized capital is very averse to risky fixed assets, preferring liquidity and easier profits.

I don’t want to suggest that capitalists are totally uninterested in Venezuela. Some are very enthusiastic, but they have a very different profile than the big oil majors that could actually redevelop Venezuela’s infrastructure. Politico reports:

“One of the things that has been incorrectly reported is that the oil companies are not interested in Venezuela,” Bessent told an audience at the Economic Club of Minnesota, according to a transcript supplied by the department. “The big oil companies who move slowly, who have corporate boards are not interested. I can tell you that independent oil companies and individuals, wildcatters, [our] phones are ringing off the hook. They want to get to Venezuela yesterday.”

As one industry insider noted, “The most enthusiastic are among the least prepared and least sophisticated.”

These types of firms are very well-connected to this administration. A Reuters report on the small and medium participants in the oil summit noted, “Several of the companies have connections to Denver, Colorado, the home turf of Secretary of Energy Chris Wright and a relatively small hub for oil and gas activity compared to other parts of the United States.”

Interestingly, the enthusiasm of small and medium capital vs. the big, publicly-traded corporate behemoths matches closely Melinda Cooper’s analysis of Trump’s business coalition, which is made up of “the private, unincorporated, and family-based versus the corporate, publicly traded, and shareholder-owned.” A 2025 analysis of the oil investment market reflected this as well: “Capital is shifting from traditional institutional investors to more flexible and opportunistic players, driven by attractive valuations, tax incentives, and infrastructure opportunities.”

This picture of a rag-tag private capital wanting to follow Trump’s filibuster into quick riches leads me to posit the very speculative theory of “dingbat imperialism,” where it’s not the big cartels, but their little cousins leading the charge down south. But in that case, it is not monopolization but a very competitive environment that is driving these risky moves. One might say this is capitalism not at its highest stage of development, but its lowest; indeed, it’s as if these firms want their chance at “primitive accumulation,” which is to say, robbery and plunder.

To add some meat to my theory of dingbat imperialism, consider the previous behavior of the majors. Rather than hawks for oil wars and free flowing crude, they’ve either wanted to lift sanctions to make their businesses easier (Chevron, Gulf refiners) or keep sanctions in place to get their legal claims from nationalization taken care of (ExxonMobil.) In this respect, they are much more like Kautsky’s “ultra-imperialists,” working within the normative structure of international agreements and treaties to cement the interests of their oligopoly, rather than pursuing destructive wars.

To a certain extent, imperialism may have always been dingbat imperialism. Historians have chipped away at Lenin’s empirical account of the origins of the colonial scramble in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In Imperial Germany, for example, the government had difficulty getting the big German banks, although highly cartelized as Lenin demonstrated, to invest in developing its colonial ventures, mostly because they were not very profitable. German banks preferred to invest in relatively safe places, like the United States, Britain, or France. British banks, much more accustomed to imperialist ventures, were willing to chip in. The government had to practically force German finance capital into Southwest Africa to prevent its colony from being totally dominated by British banks.1 Sometimes the Kaiser himself provided financial support to the endeavors. The German companies that were enthusiastic about colonial expansion tended to be speculative, “get-rich-quick” schemes. The German colonial empire was driven more by a politics of prestige and a sense of being lesser than Britain and France than by the pressure of surplus capital looking for an outlet. In this sense, perhaps, we are behaving more like the imperial upstart Germany than the hegemon Britain. Why? Maybe because Trump is himself an upstart. Dingbats all the way down.

In any case, that’s all I have of this “theory” for the moment.

Feis, Herbert. Europe: The World’s Banker 1870-1914: An Account Of European Foreign Investment And The Connection Of World Finance With Diplomacy Before The War. With Internet Archive. Council On Foreign Relations, 1961. 181-182 http://archive.org/details/europeworldsbank0000unse.

Interestingly, one can find imperialist discourses in the 19th that are closer to Trump's tweet than to Lenin's theory. For instance, in a 1884 speech, Jules Ferry justified french colonial expansion because of the need to find new outlets for exports :

"In the area of economics, I am placing before you, with the support of some statistics, the considerations that justify the policy of colonial expansion, as seen from the perspective of a need, felt more and more urgently by the industrialized population of Europe and especially the people of our rich and hardworking country of France: the need for outlets [for exports]. Is this a fantasy? Is this a concern [that can wait] for the future? Or is this not a pressing need, one may say a crying need, of our industrial population? I merely express in a general way what each one of you can see for himself in the various parts of France. Yes, what our major industries [textiles, etc.], irrevocably steered by the treaties of 1860-1 into exports, lack more and more are outlets. Why? Because next door Germany is setting up trade barriers; because across the ocean the United States of America have become protectionists, and extreme protectionists at that; because not only are these great markets . . . shrinking, becoming more and more difficult of access, but these great states are beginning to pour into our own markets products not seen there before."

(https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/readings/ferry.html)

I also distinctly remember being taught that one of the causes for World War I was Germany's problem of industrial surpluses, and the fact that unlike France and the UK, Germany did not have a colonial empire where they could sell them off (I don't know which historian was the source, though).

So perhaps, historically as well, imperialism was as much about captive markets than it was about extraction of resources.

Fully on board with the theory of an historical dingbat imperialism, too. Studying colonial history, it's often striking how much the colonial ventures were an outlet for all kinds of adventurers and misfits who had no place elsewhere. Which makes the way the misfits in Trump's administration eye over Greenland quite striking.

Wonder what Lenin would make of the most parasitic and unproductive sectors imaginable - gambling and crypto-asset trading (more gambling) - being among the few capital accumulation growth sectors in 2026.