Historical Parallels

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

It’s a natural tendency in unsettled times to seek out historical analogies that help explain and situate the present in some kind of intelligible context. I do this all the time; I think it’s an important part of sharpening one’s judgment about what’s going on around us. But if done badly, it can also hurt one’s sense of the present and, worse, lead to political errors.

Historian William Hogeland recently had a piece on his Substack called “Lame and Useless Useless US history parallels,” decrying the tendency to compare Trump’s actions to King George III and to invoke the Revolutionary Era. He writes:

The protesters are not like Bostonian resisters, ICE oppression not a revived “Lobsterback” occupation. Modern gun rights do not fulfill a founding intention to enable us to resist the tyrannical intent of those who are now deploying ICE on our streets. The error emerges not from seeing Trump’s use of ICE against the people as tyrannical—it obviously is—but from troping back to the nation’s founding in a mood of nationalistic fantasy that makes us, at best, collectively stupider than we should be, at worst less genuinely resistant to oppression.

Not that the authors of these articles are themselves stupid. They’re just bedazzled by sentiment.

I tend to think he’s right in a certain respect. Trump and his goons are much more sinister than an 18th century monarch. Modern weapons and surveillance technology necessarily make them so. A masked death squad is something darker than the gay-attired redcoats. Yet I’m not quite so convinced as Bill that the “sentiment” involved is so harmful. The use (and abuse) of the Revolutionary past has been monopolized by the Right in our era; the preservation of the revolutionary tradition and founding principles—no matter how misunderstood or distorted— is a small-c conservative ideal, and I don’t think it’s the worst thing in the world if people of a generally conservative or moderate bent see Trump as attacking some essential quality of America, because I think he is. The problem remains that the analogy is quaint, if not to say, as Bill does, lame. It neither adequately arouses the passions nor clarifies the stakes. Still, in its dowdiness and lameness, there is perhaps something gentle and nice. I’d like to imagine there are very earnest Americans out there—and they probably live around Boston, where the op-ed in question was written—who would still be inspired or incensed reading about such things in their morning paper.

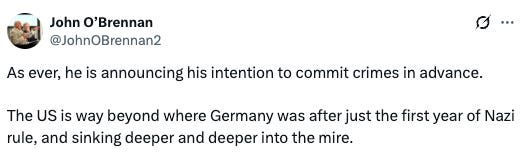

On the other end of the spectrum is a tweet I saw by a self-proclaimed “Professor of European Politics:”

Suffice to say, this is totally and utterly false. By the end of the first year of Nazi rule, freedom of the press, political competition, and organized labor had been utterly wiped out. The Reichstag Fire Decree suspended civil rights. I just want to give the reader a flavor of the severity—here’s how part of it read:

Articles 114, 115, 117, 118, 123, 124 and 153 of the Constitution of the German Reich are suspended until further notice. It is therefore permissible to restrict the rights of personal freedom, freedom of (opinion) expression, including the freedom of the press, the freedom to organize and assemble, the privacy of postal, telegraphic and telephonic communications. Warrants for House searches, orders for confiscations as well as restrictions on property, are also permissible beyond the legal limits otherwise prescribed.

The Enabling Act, in the wake of the Reichstag fire, essentially ended constitutional rule. Tens of thousands of Social Democrats and Communists had been put in concentration camps. Even before the seizure of power, political life in Germany was marred with constant violence and terror from Brownshirt thugs. I am a firm believer in the relevance of fascism to understand the present, but this is absurd. America’s democratic institutions are under severe stress, but they have not been rolled up in any way like the Nazis managed to do in just six months. Such hysteria can lead to disorganization and despair.

As Dylan Riley pointed out on Twitter, the better analogy for the present might be to Mussolini’s Italy and the Matteotti crisis. It’s not well known that for the first few years, Mussolini ruled more or less within constitutional strictures, although his movement was lawless and violent, directing a stream of terror against his opponents. In parliament, the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti rose to denounce the brutality and corruption of the regime. He was subsequently kidnapped and murdered by blackshirts, perhaps on the explicit orders of Mussolini but also perhaps not. We know his book that outlined the crimes of the fascists had outraged Il Duce, and he ranted and raved about Matteotti to his deputies. It appears that Matteotti was going to deliver a speech about a corrupt deal between the fascists and the Sinclair Oil company. The assassination of Matteotti and the subsequent investigation and trial of the dimwitted blackshirts who carried it out created a national scandal that nearly brought down the fascist government. Moderates and conservatives who Mussolini relied on for support wavered. Mussolini was in a state of near panic. Eventually, he took the advice—in effect, a threat of a coup—from the blackshirt chiefs that he had to institute a dictatorship now or else all would be lost. And so Italy tipped from what we call today “competitive authoritarianism” into the sole rule of the fascists. It was not foreordained; the mistakes and disorganization of the opposition, the cowardice and cynicism of conservatives, and the extraordinary pressure from Mussolini’s radicals all contributed to the result.

If you are interested in learning more, I wrote about the Matteotti crisis in 2022.

Still, the analogy has its problems. While there are some similar dynamics in play in the wake of the killings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, the crisis is not nearly as severe—either for the incipient regime or the constitutional order. It in no way minimizes the deaths of Good and Pretti to note that the kidnapping and assassination of a sitting member of parliament shows an advanced state of political decay. The example would be if, say, AOC or another member of the Squad were killed. The radical wing of MAGA is pressuring Trump to take ever more drastic action and “to complete the revolution,” just as the blackshirt chieftains did to Mussolini, but they are online influencers: they are presumably not gonna show up in the Oval Office and threaten to unleash violence if he doesn’t crush the opposition, which is what Mussolini’s ras did.

There are some less encouraging lessons from the Matteotti crisis, though. A fascist movement and leader can navigate a single debacle or collapse of opinion, and such a turn of events can create the conditions where a fascist government might take desperate action to preserve the regime.

Finally, in the New York Times, Samuel Moyn and Jack Goldsmith have an article comparing Trump to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Goldsmith is a former government lawyer and Harvard Law professor who runs the terrifically helpful Executive Functions substack, and Moyn is a professor at Yale. Moyn, of course, assured us for years that all the analogizing to fascism was foolishness and that the real problem was liberal “tyrannophobia.” To put it mildly, I do not think Professor Moyn has proven himself to be a person of sound judgment. Apparently, he has not been shamed by events into avoiding this somewhat cheeky comparison. On the contrary, he seems to relish the chutzpah.

The comparison is not so dumb in certain ways. It’s kind of obvious that any big change in the constitutional order, broadly understood, is going to harken back to the New Deal and FDR, since that was the big one in the modern age. I remember joking to Jamelle Bouie shortly after the inauguration that I understood what small government conservatives must have felt like during the institution of the New Deal in all their fury and despair. The comparison is not original: Jedediah Purdy and David Pozen articulated the “constitutional-regime-change” position in a piece in the Boston Review from October.

But the strangest thing about the piece is how it has to admit the decisive differences between FDR and Trump:

To take the true measure of this presidency so far, therefore, we must acknowledge the increasing self-aggrandizement of recent executives, none of whom have been able to consolidate a paradigm shift in American governance, ruling as they all have amid democratic disagreement and legislative gridlock. Roosevelt, by contrast, went from strength to strength, with greater electoral popularity in the 1934 midterm elections and his re-election in 1936.

From this perspective, Mr. Trump — precisely by attempting to do so much with the presidency’s tools, honing their sharpest edges yet further — is showing that no president can reconstruct the political order with brittle support that is the hallmark of presidents in our time.

Okay…

FDR did use executive power to a degree unheard of in American history, to the point, yes, but crucially, he also had a big congressional majority and vast enthusiastic public support. The New Deal order is called an “order” because it involved not just decrees but lots and lots of significant legislation from Congress and long-lasting institutions, many of which these people are trying to destroy, but without any clear replacements. This lack of mass public buy-in and a hegemonic coalition is exactly why people like me wanted to bring up the history of fascism in the first place: in the absence of mass consent, the Trumpists seek to use coercion at every turn. This is the phenomenon Gramsci called “Caesarism,” an authoritarian push that results from a deadlock: the inability of either side to effectively rally the nation to their program.

In any case, I hope you found this discussion of historical analogies somewhat illuminating.

With respect to the Matteotti comparison - the murder of Melissa Hortman was alarming to me! I do think it matters that she was a member of the Minnesota state legislature and not the national one, but it's a bad symptom of civic decay and it's alarming that almost everyone seems to have forgotten about it

That tortured attempt to conflate Trump and FDR offers really compelling evidence that people who lose their faith will sometimes convince themselves they’ve gotten it back by adopting bad faith as their personal religion.