Some Thoughts on Antisemitism

In the most recent issue of Jewish Currents, the editors of the magazine have a piece entitled “How Not To Fight Antisemitism.” I understand it’s generating some controversy and my initial reaction to it was also negative, but I read it more carefully and found that it actually made some good points. I hadn’t planned on responding to the article at length, but yesterday a few things banging around on Twitter, including a segment from Tucker Carlson and tweets from would-be Senator J.D. Vance and actual Senator Josh Hawley as well as the increasingly unhinged locutions of “anti-wokeness” crusader James Lindsay, prompted some reflections on antisemitism, which I’ve decided to try to get down.

The piece in Jewish Currents lamented the tendency of focus on antisemitism in activist circles to devolve into clumsy or even patently bad faith “readings” of the presence of antisemitic tropes everywhere in discourse or the centering of the importance of Jewish suffering above groups that are actually in more vulnerable positions in the contemporary U.S. The authors’ points are well-taken, but I would just note that both Jewish and African-American history are full of examples where episodes of relative material prosperity and security provided no guarantee of safety in the long run. The authors point to a lot of absurd histrionics, like the following:

Among very online lefty Jews, “Christian hegemony” became a buzzword that could be listed among the various oppressions plaguing American society, and named as the cause of supposed microaggressions like the singing of “Amazing Grace” at vigils held after Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death or psychic injuries stemming from exposure to Christmas.

I think this type of display stems less from the question of antisemitism than the tendency in contemporary political activism to foreground the experience of individual psychic harm and to make the focus experiences of discriminatory behavior. This is not in the slightest to deny that these experiences exist and can be truly frightening and demoralizing, but when they become the only source of authority to talk about antisemitism they depoliticize it and make it a matter of individual experience: It can’t be real if you yourself haven’t suffered it, so therefore you must demonstrate you’ve suffered from it: one must seize on the moment of offense and make the most of it. This leads to these kind of embarrassing things where people declare it oppressive or even traumatizing when Amazing Grace was sung at a vigil for RBG or that Christian Seders are culturally appropriative or whatever.

The fact of the matter is that individual episodes of explicitly discriminatory or hateful behavior towards American Jews is fortunately pretty rare at the present moment, especially if you live in a large, diverse city and you are not identifiably Jewish through your clothes or hair. Such episodes are not, however, nonexistent or negligible: recently there have been horrific attacks on Orthodox Jews, particularly vulnerable because they are so easily identified, and then there was the Tree of Life synagogue massacre, which was directly spurred on by the spread of antisemitic political ideas. But I think the paramount importance given to individual episodes of suffering or the recounting of slights makes whats properly political too often a matter of isolated personal experience, which can be doubted or discounted, often in bad faith, in piecemeal. Political action fundamentally requires individuals to join together in solidarity, not be divided into innumerable atoms of trauma. These conventions also occasionally require people to demonstrate their bona fides as sufferers by bringing up very painful episodes of family history, recollections that become all the more painful when you are faced with a hostile crowd that might doubt or denigrate the importance your most sacred memories. Then there is the uneasiness or guilt of “using” these memories for political goals, the pursuit of which always involves a contest for power and authority, no matter how noble or just the ends. In any case, as powerful and necessary as personal testimony can be, trauma and historical pain should not be the sine qua non for speaking publicly: it both asks the traumatized to make themselves vulnerable and creates the natural temptation to exaggerate for rhetorical effect, a normal part of political behavior whose equally natural and, even healthy, consequence will be the growth of skepticism in the audience. The unhealthy outcome of this becomes the growth of cynicism and suspicion of personal motives.

I’m not an activist and therefore have the luxury of speaking in a different language than is required of that world. Nor is it my intention to direct or correct the tactics of activists who I imagine know their business far better than I do. I’m not going to pretend I really know how to “fight” anything,—I’m not a politician or a soldier. But I do think it’s important to occasionally “center,” to borrow from activism language for a moment, the discussion of antisemitism. This is not to privilege the uniquely terrible suffering of the Jews over other groups, but to more clearly understand how racism functions as a specifically political factor and not as just a vector of social discrimination.

An important thing to understand about antisemitism is that it’s not coterminous with simple “Jew-hatred” or prejudice;—rather it's a particular type of obsessive preoccupation with and fantasy about the presence of an alien force in the national body. I also believe it’s very difficult to understand the type of politics being practiced by Tucker, Vance, Hawley, Lindsay et. al. without understanding the history of antisemitism, which emerged as a properly political force and an ideology in the late 19th century. Jews were not just singled out as Jews, but were given a structural role as the cause of various social maladies, variously liberalism, socialism, or capitalism. Sometimes it was presented that these modern dislocations were fundamentally Jewish in character, sometimes the problem was posed that Jews were just excessively associated with these institutions. Antisemitism always came packaged other fears and hatreds: of immigrants, of other supposed conspiratorial cliques like the Freemasons, of urban life, of disturbing modern cultural forms, etc. Antisemitism was always a synthesis of reactionary ideals and myths: it focused the tangled problems of modern society onto a single, identifiable enemy-figure.

Here’s how French historian Michel Winock describes the political effects of antisemitism in late 19th century France:

…this was the true political function of anti-Semitism: as soon as indigent mobs—small businessmen and artisans victimized by the economic evolution—exploited workers, and peasants forced to leave the countryside were shown the Jew was responsible for all their ills, social conservatives had an inestimable weapon. Deriving strength from their control of the press, they orchestrated the developing myth for their own use. Class conflicts vanished: there was now nothing but the minority of Jewish profiteers crushing the vast majority of their Aryan and Catholic victims. 1

“In establishing anti-Semitism as a system of universal explanation, [the antisemitic writers] made the Jew the negative pole of nationalist movements: it was in relation to the Jew, against the Jew, that nationalists, defined their French or German Identity,” he continues. “They were proud to belong to a community and to know clearly who the adversary was who threatened its unity and life.” Or, as another historian of France, Nancy Fitch, writes, “Dreyfus, the Jewish traitor, appeared almost miraculously in 1898 to save the cause of anti-parliamentarian conservatives.”2

This identification of Jews with the perils of modernity did not just take place in France. Fritz Stern, in his study of reactionary ideologues in late 19th century Germany writes, The Politics of Cultural Despair, writes:“The Jews had "natural allies, the liberals," and Lagarde's attack on them was more pervasive, if less vitriolic, than on the Jews. Like most of the Germanic critics after him, Lagarde thought that both Jews and liberals were the agents of subversion, conspiring against the true Germanic society of faith and hierarchy. For Lagarde, liberalism was not primarily a political creed nor a particular set of political institutions; it was the dominant, diabolical, and thoroughly alien force in German culture, the force impelling toward sham and modernity.”3 Or, on another writer: :....it had become an article of faith that Jews and modernity were one, and the fury of his anti-Semitism sprang from his resentment of everything modern. He hated the Jews for encouraging the Germans to succumb to science, democracy, and educated mediocrity.”4

Americans don't actually have much experience with this form of political antisemitism, and for the most part only understand antisemitism as the explicit, negative, prejudicial mistreatment of Jews, which, once again, is today fortunately pretty uncommon in the U.S. But antisemitism does lurk at the edges of American political culture and often serves as a glue and an impetus, particularly for factions that bitterly resent what they feel to be a marginal status in the political scene.

In the American experience, certain forms of anti-blackness, particularly where the presence of blacks in the country is presented as a threat to national order and health, come quite close to having the same structure and function as political antisemitism. Today, with the integration of blacks into the middle class, and into the highly visible worlds of mass culture and politics, this type of “anti-black antisemitism” or “antisemitic anti-blackness,” if you’ll permit me, with its status resentments, fears of “foreignness,” and racial contamination, is quite salient. I was taken aback by how similar the negative responses to the election of Léon Blum, the first Jewish premier of France, and those of Barack Obama, sound. Blum, born in France, was derided in the right-wing papers as a foreign threat, as being “not from around here,” and his very presence signified the betrayal of the nation. Indeed, the attitude became that even literal foreign invaders were preferable: the phrase “Plutôt Hitler que le juif Léon Blum” —Rather Hitler, than the Jew Blum—was to be heard on the lips of some. Far from being the vector of national unity, the appearance of antisemitism was both sign and cause of the nation’s ultimate demoralization and defeat.

Unfortunately, trying to identify the appearance of more political forms of antisemitism often devolves into sort of quasi-literate "trope hunting", which just makes talk of political antisemitism sound more phantasmic and hysterical. It also can make people who try to “call out” antisemitism look touchy, paranoid, or even opportunistic, not for nothing all negative stereotypes about Jews. The fact that accusations of antisemitism can be used either clumsily or even in bad faith is unfortunate and maybe even deleterious, but in the final analysis is really kind of neither here nor there. But the fact remains that even the educated American public has not developed a very keen judgment about antisemitic politics, particularly when they are being practiced in ways that are sneaky or inchoate.

Can one be antisemitic without fully intending to be? Or rather, can we identify antisemitism without clear intent or explicit content? Of course we can. Look, for example, at someone who is extremely irresponsible like Tucker Carlson, who routinely trots out bits and pieces of white supremacist and antisemitic propaganda, with the most explicit parts carefully left out. He mentions “The Great Replacement” theory, without elaborating the full neo-Nazi version of the theory with the Jews doing the replacing of whites with minorities. In doing this he titillates but also frustrates the more hardcore members of his audience, who want him to explicitly “go there” and name the racial enemy. Antisemitism, like Disraeli said of the East, is a career, and Carlson, who has had to reinvent himself after failures and disappointments, is arriving at an old path available to failures and rejects since the 19th century.

James Lindsay, an anti-woke crusader, who is now also flirting with antisemitism, shows just the tendency of political notions that posit shadowy cabals and conspiracies tend to end up on the Jews as the most convenient and opportune concretization. Wokeness, presented as a kind of out-of-control, disruptive liberalism, is increasingly being given an ethnic character in his harangues, just as liberalism, socialism, and capitalism were once given the same treatment by the classic crop of antisemites.

The echoes of the phrase “Solution to the Woke problem” and the air of menace here should make anyone of good conscience shudder with disgust. His audience understands what he’s saying and, again, wants him to go further.

Sartre writes in Anti-Semite and Jew, that antisemitism is not an opinion or a view, it’s a passion: it becomes the organizing principle of people’s lives, an obsession, and therefore a kind of existential dodge of full personhood. I think there’s a lot of truth to this, but without pondering the abysses of the inner life it’s also important to observe that antisemitism is also seized upon opportunistically, as a method of organizing politics or careers. Charles Maurras, the anti-Dreyfusard ideologue, wrote, “Everything seems impossible or terribly difficult without the providential appearance of antisemitism. It enables everything to be arranged, smoothed over and simplified. If one were not an antisemite through patriotism, one would become one through a simple sense of opportunity.”5 (Emphasis mine.) But Sartre is undoubtedly correct when he identifies a certain type of enjoyment attendant to antisemitism, a pleasure we can detect in those who like to flirt at its edges—they “delight in acting in bad faith,” they are “trolling” to use the contemporary lingo:

I think whenever there's an effort to synthesize various perceived maladies of the modern condition into a single figure of “enemy,” antisemitism becomes a relevant topic of discussion. We see this happening in two types of contemporary right-wing discourse: a certain flavor of right-wing populism, with its need to define a corrupt elite holding down the honest folk, and also “anti-wokeness,” which is also grasping around for a concrete subject that can be made the agent of the cultural shifts it finds disruptive and dislocating.

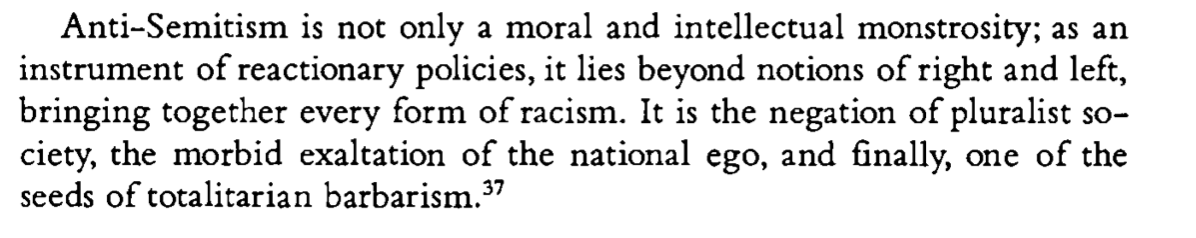

Jews themselves might not end up being the concrete enemy singled out in every instance, but the history of antisemitisms is nevertheless an essential touchstone to understand the type of politics being practiced. Just the fact of the rampant popularity of dark, conspiratorial political beliefs makes antisemitism a vital subject of inquiry. Of course, this is not at all to say there cannot be criticisms of social elites or identity politics or whatever that are not redolent of antisemitic “tropes;”—of course there can be; just as there are many serious critiques of capitalism, socialism, and liberalism that do not indulge in such fantasies, but it’s clear that we’re seeing certain types of rhetoric that perform similar, if not functionally identical work, to classic antisemitism. This does not mean we should all start to jump at every shadow and fear that every nasty remark is a “track laid on the way to an American Auschwitz,” to quote the Jewish Currents editors, but hopefully the history in question can help us refine our political judgments and be clearer about what’s going on. And yes, I do think we should reflect on what type of politics’ final terminus has been in the past, as remote or unlikely as it may appear in the present moment. To conclude with another quote from Winock, —

Michel Winock, Nationalism, Anti-Semitism, and Fascism in France, pg. 98

Fitch, Nancy. “Mass Culture, Mass Parliamentary Politics, and Modern Anti-Semitism: The Dreyfus Affair in Rural France.” The American Historical Review, vol. 97, no. 1, 1992, pp. 55–95. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2164539. Accessed 10 Apr. 2021.

Fritz Stern, The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in The Rise of The Germanic Ideology, pg. 64

Ibid., pg. 142

Zeev Sternhell, The Birth of Fascist Ideology, pg. 85

Short step from the "Judeo-Bolshevism" of old to modern accusations of "Cultural Marxism". Seeded by nuts in the Lyndon LaRouche right, now it's not unusual for mainstream rightwing figures to talk about the insidious, far-fetched influences of The Frankfurt School.

Really great. You've asked online what folks like best about The Blog, and I thought this was a pretty neat example of why I appreciate it: taking up discourse that's pervasive but not reckoned with, and then taking the reader through a serious explanation of what might otherwise be taken as a rhetorical dispute ("This is anti-semitism!" No it's not!"). I'd actually be interested in an even deeper dive into the connections between deployments of "Wokeness," "Cancel Culture," and anti-semitism/racism (perhaps particularly as it pertains to the same characters' -- Tucker, Lindsay, and Hawley -- misrepresentation/scapegoating of "Critical Race Theory."