The End of the Affair

Part X: Abandoning the Illusion

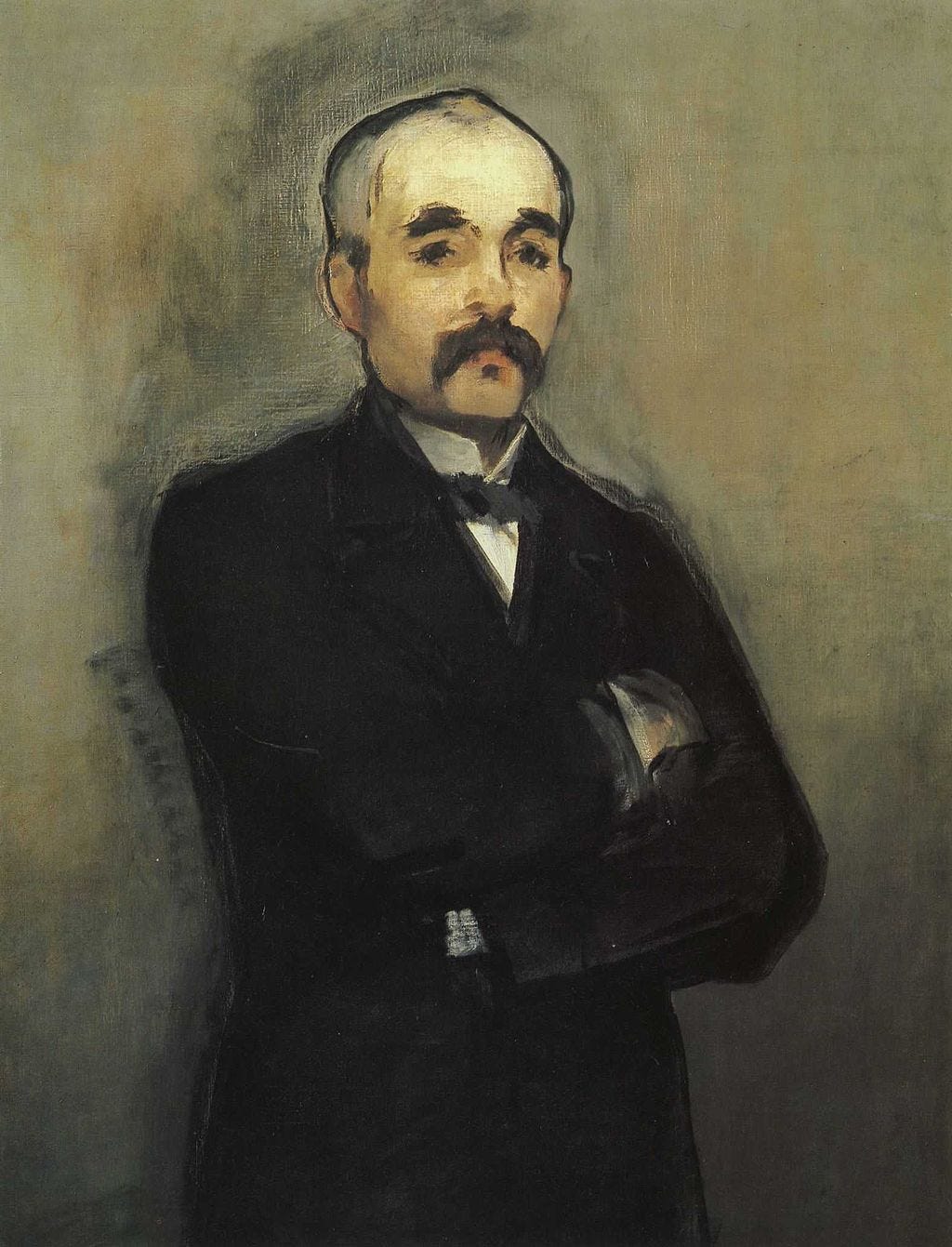

The offer of a pardon by the Waldeck-Rousseau government posed a deep problem to the Dreyfusards: the acceptance of a pardon would imply an admission of guilt. But the sentence of ten years imprisonment imposed by the second court-martial would certainly kill Dreyfus, his physical and mental health nearly destroyed by his stay on Devil’s Island. Joseph Reinach favored the acceptance of a pardon, no doubt out of concern for Dreyfus and his family, but he also attached a political logic: with the offer and acceptance of a pardon immediately it would be equivalent to “tearing up” the verdict. No doubt the former deputy was engaging in some light casuistry to persuade his fellow politicians. It didn’t work. Georges Clemenceau, the always-intransigent Radical, combining a Jacobin fanaticism and an insatiable political ambition that are difficult to fully disentangle, went nearly berserk, condemning the idea of a pardon in the most violent possible terms. The essential to thing to Clemenceau was to carry the war against the Army and the religious orders to its decisive conclusion and anything less than that was an act of cowardice: he declared he didn’t care what happened to Dreyfus as an individual: “I am indifferent about Dreyfus, let them cut him into pieces and eat him.”1 The affair was now a symbolic struggle and a matter of abstract principle: it would not be easy to wean intellectuals and politicians off the high provided by those stimulants.

Even Mathieu Dreyfus was convinced initially that his brother should refuse the pardon and, swept up by Clemenceau and Jaurés’s rhetoric at a fevered public rally, declared, “‘No. Never will I advise my brother to withdraw the request for revision. He will die in prison. So be it! His death will be on the conscience of the ministers!”2 It didn’t take too long for Reinach to convince Mathieu to favor for the pardon option: he painted a picture of Dreyfus safe at home with his family that quickly put to rest Mathieu’s desire to sacrifice his brother on the altar of principle. Alfred Dreyfus, always insistent on his innocence and pre-occupied with his honor, was hesitant to accept as well, but the prospect of quickly reuniting with his wife and children proved to be overwhelming. Gradually, Reinach, with his great reserves of humor and patience, persuaded the major Dreyfusards to reconcile themselves to a pardon to save Dreyfus from further suffering.

Some, like Picquart and Labori, who had both suffered as well in the Affair—Picquart had been imprisoned for a year, Labori shot and nearly killed by an unknown assailant—continued to believe that the acquiesce to a pardon was a shameful act that put personal interests above those of the public. Their characterization of the negotiations of Reinach and the Dreyfus family with the government shaded into antisemitism: characterizing the Jewish Dreyfusards as being selfishly and clannishly concerned with saving one of their own. The propaganda phantasm of the “Jewish syndicate” penetrated successfully penetrated even the Dreyfusard ranks. Picquart’s prejudices, overcome by his sense of duty and perhaps the excitement of the Affair, returned.

The Dreyfusards quarreled internally, denounced and mocked one another. They now lacked the central uniting factor that had kept this coalition of such different temperaments, ideologies and class-backgrounds together. Many now longed for the sense of purpose and camaraderie. And also for the grandeur and excitement. Picquart melancholically remarked to Reinach, “One must never believe in the success of something conceived too much in beauty.” Reinach replied, “Decidedly we…for the past two years have been living in too heroic, too Wagnerian a world, outside of common humanity. We have lost the notion of what humanity is. We stubbornly believe that it is capable of making an effort. We must abandon this illusion.”3

Of all the Dreyfusards, the Socialist Jean Jaurés was best able to reconcile the human concern for Dreyfus with the philosophical imperatives of justice. He was helped by a cultured and humanistic understanding of the revolutionary tradition:

For Socialists, the value of every institution is relative to the human individual. It is the human individual, affirming his will to be free, to live, and to grow who henceforth is to bring life to institutions and ideas. It is the human individual who is the measure of all things, of country, family, property, humanity, and God. That is the logic of the revolutionary idea. That is socialism.4

Jaurés assented to the pardon on the condition that the Dreyfus family keep up their fight for his total exoneration and helped Alfred to draft his statement to that effect. Jaurés and Dreyfus were to remain friends, despite their political and social differences. Jaurés was assassinated by nationalist student in 1914 as World War I broke out. He had been killed for being a prominent voice for pacifism; Dreyfus, whose patriotism never wavered, was recalled to active duty.

Waldeck-Rousseau paired his pardon of Dreyfus with a general amnesty of all crimes that had been committed in connection to the Affair. Jules Guérin and Paul Déroulède would go free, but the amnesty was not extended to the arch-antisemite Édouard Drumont, now facing civil repercussions for provoking the attempted assassination of Labori. The Dreyfusards notwithstanding, France seemed ready to move on and forget. The year 1900 held the promise of a World’s Fair in Paris and the country was eager to show its best side to the international community.

The political left had seen its position improve over the Affair. Jaurés pointed to the presence of a Socialist minister in Millerand. Some comrades were not convinced and denounced his “conservative” acquiesce to the bourgeois republic. Jaurés defended the Millerand’s presence in the government of “Republican defense” before the International Socialist Congress:

To be sure, society today is divided between capitalists and proletarians; but at the same time, it is threatened by the offensive return of all the forces of the past, by the offensive return of feudal barbarism and the omnipotence of the Church; and it is the duty of Socialists, whenever republican freedom is at stake, when freedom of thought is threatened, when the ancient prejudices which revive the racial hatreds and the atrocious religious quarrels of past centuries seem to be being reborn, it is the socialist’s and proletarian’s duty to march with those fractions of the bourgeoisie that do not wish to return to the past.5

Jaurés carried the day for now, but a new split was brewing in the Socialist movement. A growing contingent of activists viewed the Affair as “an enormous hoax” and the defense of liberal democracy had “placed the organized might of the proletariat at its disposal” and “the only tangible result of their victory had been the rise of Radicalism and the transformation of the Socialist party into a parliamentary party like all the others.” All these new “attacks on liberal democracy…shared one overriding concern: stemming the tide of Dreyfusism that threatened to swamp the working class.”6 Some of these critics of socialist rapprochement with liberal democracy would go on to form their own ideological responses, which would come to fruition in the next century.

The election of 1902 resulted in even stronger returns for the left: the bloc des gauches, the coalition of Socialists and Radicals, took 57% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies, in what was essentially a referendum on Waldeck-Rousseau’s policy of Republican defense and his vigorous dismantling of the power of the Catholic religious orders. Jaurés regained his seat; Drumont lost his.

In 1906 the High Court of Appeal finally declared Dreyfus innocent. The Senate reintegrated Dreyfus and Picquart into the Army and Dreyfus was awarded the Légion d’honneur. Clemenceau would become prime minister and appoint Picquart his minister of war. Nothing could fully put out the embers of anti-Dreyfusism. The anti-Dreyfusard press continued to insist on his treason and the existence of a vast Jewish infiltration of French institutions. In 1908, at a ceremony to move Emile Zola’s ashes to the Pantheon, Dreyfus was shot and wounded in the arm by a member of Action Française and associate of Drumont. The assailant was acquitted.

Alfred Dreyfus died on July 12, 1935. His funeral procession was attended by troops gathered for Bastille Day celebrations. The Third Republic was now embroiled in a new set of crises whose roots can be found in the Dreyfus Affair. Those crises will be subject of the next series here. In the meantime, I will leave you with Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the Affair:

Down to our times the term Anti-Dreyfusard can still serve as a recognized name for all that is antirepublican, antidemocratic, and antisemitic. A few years ago it still comprised everything, from the monarchism of the Action Française to the National Bolshevism of Doriot and the social Fascism of Déat…What made France fall was the fact that she had no more true Dreyfusards, no one who believed that democracy and freedom, equality and justice could any longer be defended or realized under the republic. At long last the republic fell like overripe fruit into the lap of that old Anti-Dreyfusard clique which had always formed the kernel of her army, and this at a time when she had few enemies but almost no friends…Certainly it was not in France that the true sequel to the affair was to be found, but the reason why France fell an easy prey to Nazi aggression is not far to seek. Hitler’s propaganda spoke a language long familiar and never quite forgotten. That the “Caesarism” of the Action Française and the nihilistic nationalism of Barrés and Maurras never succeeded in their original form is due to a variety of causes, all of them negative. They lacked social vision and were unable to translate into popular terms those mental phantasmagoria which their contempt for the intellect had engendered.7

Ruth Harris, Dreyfus, pg. 391

Ibid., pg. 390

Ibid., pg. 392

Jean Denis Bredin, The Affair, pg. 496

Ibid., pg. 444

Zeev Sternhell, Neither Left Nor Right: Fascist Ideology in France, pg. 52

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, pp. 215-216

Thanks so much for writing this, it’d been enormously informative. I’m very much looking forward to the next series!

this has been great!